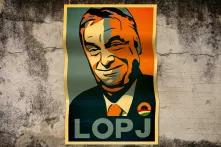

Was Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s system of governance in Hungary built legally after 2010? Were the ruling party’s efforts to remove individual pillars of the rule of law themselves lawful? Can these be rebuilt lawfully? Should those responsible be held accountable? What might be done with Orbán’s political system after a potential opposition victory in 2022, considering that it is built mostly on informal power and privatized economic-financial resources? These questions are currently being debated mainly as issues of public law. Unfortunately, little is being said about the sociopolitical requirements for the democratic transition the opposition so desires.

The opposition is still not united on defining the current system

One of the Orbán regime’s key legitimizing tools is that it can interpret its governance and its politics to its own electorate as a coherent, easy-to-understand, simple framework. Meanwhile, the opposition has not managed to find their own way to relate to the current system over the past decade.

The opposition mostly agrees that Fidesz’s strategic goal is to establish an authoritarian political system that makes those in power irreplaceable in the long term. Thus, the ruling party has followed a well-thought-out, three-step agenda, first occupying positions of political power and institutions, then economic/financial positions, and finally occupying the cultural sphere. The whole process has been accompanied by the gradual takeover of the media. However, the opposition parties’ views on whether the ruling party can be replaced via elections differ widely.

Certain political actors often deem the system a ‘dictatorship’ where independent institutions serve a decorative role only - but they still file complaints with the police, the ombudsperson or the Constitutional Court, and they continue to sit in the National Assembly. Meanwhile, political parties, the intelligentsia, and the media endlessly debate how to define the system (e.g., hybrid regime, illiberal system, etc.), which might be interesting intellectually, but leaves the opposition and their electorate in complete uncertainty as to what would follow an opposition election victory in April 2022. The potential assessments are vastly different: Some individuals think the government would be a lame duck without a two-thirds majority, which would reduce the scope of its decisions to matters such as where to install bike lanes, while those at the other extreme of the scale say the Fundamental Law is illegitimate and can therefore be repealed completely, prompting a new constitutional process and the establishment of a new public law system.

The opposition parties have therefore not been consistently using any particular definition of this political system. It is thus often ambiguous whether a given opposition party represents “just” anti-government views or anti-system view more broadly which means there is no consensus among them as to which political tools are adequate. In that case, the question remains unanswered as to whether anything exists that could create a strong, united expectation among opposition voters and lay the foundation for the legitimacy of a democratic transition and a renewed constitutional effort.

Hungarians do not trust institutions, only those who control them

In Hungarian society, trust remains low, both interpersonally and in institutions. Due to political polarization, trust in political institutions depends mostly on who is in government and in opposition. Before 2010, the supporters of the parties then in opposition and its politicians did not trust institutions, just their own political representatives at best. After 2010, the formerly- governing political actors who had been forced into opposition then became distrustful of those very same institutions. Democratic norms became tools: Political actors did not respect rules and institutions, but those who were controlling them. The Orbán regime used this polarization and weak trust in institutions to degrade and hollow out the rule of law.

The desire to re-establish the rule of law supposes that at least the opposition supporters might consider such institutions to be important enough to save. However, this is not actually the case, and currently it is unknown how such trust could be rebuilt. The opposition’s political actors would have to work a lot more to create that trust; without such efforts, just their own voters would be those who might trust even independent institutions that potentially operate in a more autonomous manner.

Desire for accountability

These efforts to weaken democracy and the rule of law have played a large role in degrading the efficiency of the state institutions fighting corruption. Hungary has experienced a “reverse” state capture. In contrast to classic state capture, when a weak public administration is taken over by influential economic circles, in Hungary the public administration is taking more and more control over economic actors, even monopolizing a considerable part of certain economic sectors (e.g., construction, energy, transport, media, tourism, advertising, etc.).

Is it true that the Hungarian electorate is not much bothered by this systemic corruption, as certain opinion leaders and opposition politicians state? Is it not an issue that some parts of the opposition are not credible enough to represent the fight against corruption and for accountability?

Societal apathy concerning corruption, which is often misinterpreted, is not about the electorate’s lack of interest in or concern over corruption, but mainly means they either feel powerless about it or see no solutions for it. Hungary’s system of political institutions hinders accountability substantially. Thus, dissatisfaction with corruption leads to frustration and apathy. The opposition has now put accountability on the list of its campaign messages. If it manages to translate accountability into practice, it would offer a new experience, an almost cathartic one, to the voters (and not just opposition voters) of a kind that has not been seen in the past 30 years – neither after the events of 1989-1990, nor after Viktor Orbán’s accession to power post-2010. However, there are not many signs that this promise of accountability could become more than an empty campaign slogan.

The power of a united opposition

Whichever answers the opposition gives to these questions, it will have to formulate them in an understandable way and make the electorate accept them during the six months following the opposition primaries this autumn. The opposition, made up of six political parties, will be selecting its 106 candidates in single-member districts and its prime ministerial candidate through primaries for the first time. This process will certainly not be without conflicts, but it could even unify the currently disunited opposition and lay the foundations of an electoral victory and a chance to replace Fidesz’s system. However, debates and conflicts would be coded into a six-party coalition even in a model democracy, and these could be heightened when the common task is launching a democratic transition. There are no guarantees that they would be able to achieve this and avoid crumbling under the weight of the Fidesz empire, which even if it were forced into opposition would remain stronger than they are.

The situation would be new, but not unprecedented. The opposition’s campaign and results in the 2019 municipal elections put Fidesz in a tough spot: The myth of the ruling party’s invincibility fell apart and a potential counterbalance was created to Fidesz’s power in the capital and 10 larger cities. The municipal elections two years ago were mainly about voters’ political opposition to Fidesz.

Nevertheless, opposition politics remains indebted to the electorate: Despite promises and multiple initiatives, those opposition-led municipalities have not become a political force capable of united action, they have not created their own joint public space, and there have been no visible efforts regarding accountability in the cities where they govern. This is an experience the opposition has to learn from during their preparations for the general election. The question is whether they will be able to do so.

This article was first published by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Prague office.