Böll EU Brief

Northern EU enlargement in sight? Seizing momentum in uncertain times

Böll EU Brief 04/2025

In the media: Spiegel, Project Syndicate, L'Echo, European Pravda, The Korea Times, Portfolio.hu, Noah.dk, De Volkskrant

Key findings:

-

A geopolitical window of opportunity has opened up: the new strategic context created by Russia’s war and Trump’s return have prompted shifts in public opinion in Iceland, Norway and Greenland. Northern EU accession is becoming a political possibility that requires attention.

-

Bundling enlargement could help build momentum. A carefully sequenced enlargement round that includes both Nordic and southeastern and eastern candidates could reinvigorate a fatigued debate. In particular, pairing Ukraine’s accession with Norway’s could shift the narrative from burden to opportunity.

-

Fisheries remain a political fault line for the Nordics. This means the EU should make an offer too good to ignore. However, the EU needs to be careful to only incentivise, rather than push, EU accession. An EU signal towards Iceland, which intends to hold a referendum by 2027, could help sustain domestic momentum, while Denmark’s EU Council presidency could particularly elevate the issue.

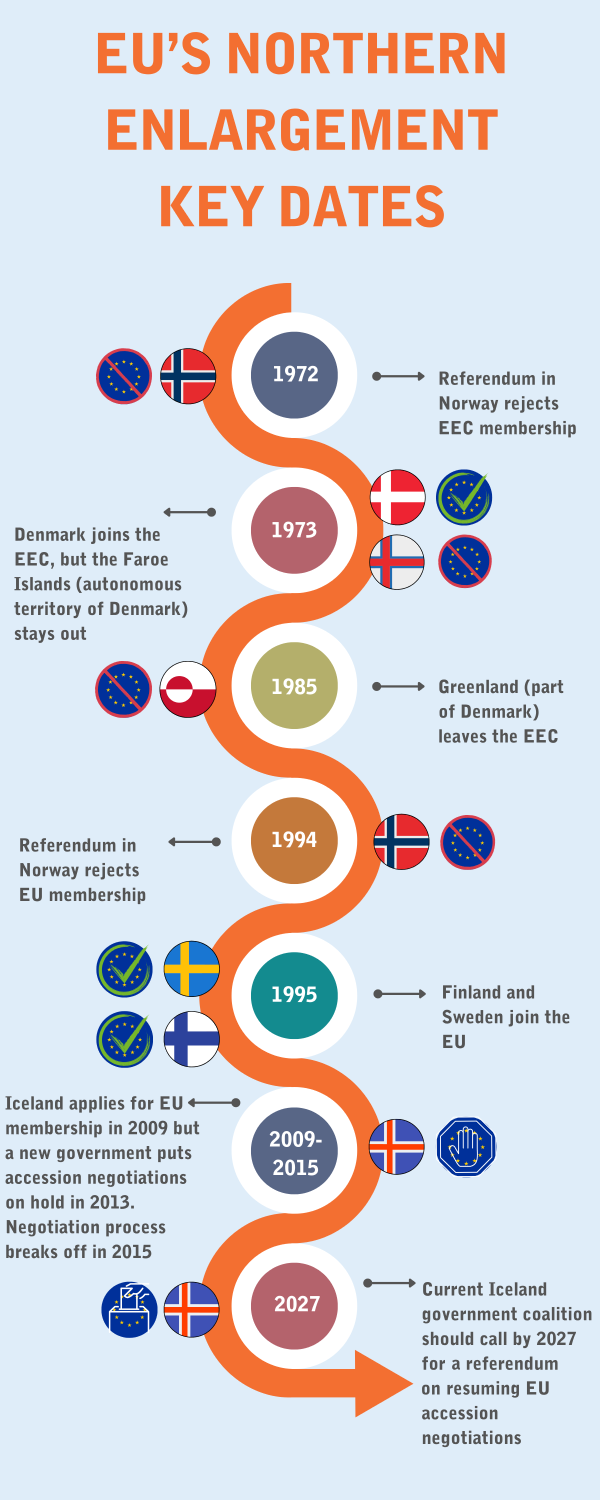

Recent geopolitical developments have given the debate on northern EU enlargement a new boost. Iceland’s new government has promised to hold a referendum on the country’s EU accession by 2027 at the latest, and the gap between the yes and no camps is narrowing in Norwegian opinion polls, with a recent poll showing 41 per cent for and 48 against.¹ Greenland has been in the eye of a transatlantic storm, with President Donald Trump’s repeated threats to annex the island, not excluding by military means.² In the latest poll from December 2024, 60 per cent of Greenlanders were in favour of rejoining the EU.³

The focus in European security was strongly centred on NATO immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, with Finland and Sweden’s subsequent accession reviving the alliance that France’s president Emmanuel Macron had deemed “brain dead” in 2019.4 NATO’s forceful comeback seemed to cement the division of labour between the transatlantic alliance as the only viable European defence arrangement and the EU as a political union with little role in defence beyond regulation and finances. However, Donald Trump’s return to the White House has reversed the dynamic to focus more attention to the EU as a security and defence actor.

The Nordic countries’ experience with the benefits of being united in NATO have had a positive spillover effect into the EU debate. This was recently highlighted by Iceland’s president Halla Tómasdóttir, who argued that in the current security situation, the Nordics have to close ranks and contribute to strengthening Europe as a united Nordic bloc – including potentially within the EU.5 At the same time, Ukraine and Moldova’s EU integration is progressing, but not without contestation.

Combining the Nordic and Eastern enlargement – widely driven by the same geopolitical necessities – into one round could help change the overall enlargement dynamic.

Encourage Nordic interest, but don’t overdo it

The situation in both Norway and Iceland, however, remains sensitive. Norway applied for EC membership twice in the 1960s, but the whole accession round was rejected both times due to French president Charles de Gaulle’s objections to the UK’s membership. Norwegians later voted against EC/EU membership in a referendum in 1972, and again in 1994, when Sweden and Finland decided to join the EU. Iceland applied for EU membership in 2009 but broke off the negotiation in 2015 after a change in government two years earlier. Greenland left the EU in 1985, following a referendum in 1982, in which 52% voted to leave, particularly due to concerns regarding the EU’s fisheries policy.

A successful northern EU enlargement round would therefore require a carefully calibrated strategy by the Icelandic and Norwegian (and Danish/ Greenlandic) political leadership, as well as by European partners and the EU institutions.

While France, for example, has taken a forward-leaning position, offering Denmark to send troops to Greenland in January and with President Emmanuel Macron visiting Greenland as the first European leader after Trump’s annexation threats, partners should tread cautiously in order not to risk generating backlash.6

The EU has to remain strictly a part of the solution and avoid becoming part of the problem for Norway, Iceland and Greenland, especially when transatlantic tensions are increasing. The democratic processes can be encouraged, but not rushed.

Norway contributes significantly into the budgets of the EU programmes and agencies it has chosen to participate in, such as Frontex and the EU border and coast guard agency. Based on a framework agreement from 2004, Norway has also participated in a number of both military and civilian EU crisis management operations. Norway contributes to the European Defence Fund and the European Peace Facility. In 2024, Norway signed a partnership agreement on security and defence with the EU.

In short, Norway has chosen the closest possible partnership with the EU just below the threshold of membership, much like Finland and Sweden’s relationship with NATO was until accession in 2023 and 2024, respectively. And like its neighbours with regard to NATO, Norway is facing the disadvantages of participation without membership: in January 2025, the government collapsed over the implementation of the EU’s energy market rules. Another concrete example that highlights the urgency to make Norway’s “situationship” with the EU official is the danger of being caught in the crossfire of the tariff war between the US and the EU. This contingency prompted a large Norwegian delegation, including 30 business leaders, to travel to Brussels in April 2025 to ensure goodwill in the EU.7 There is awareness in Norway that the current EEA deal comes with a lack of influence, but a majority of Norwegians remains fine with it, as the EEA agreement has been sufficiently beneficial – until now.8

Recommendations

That Iceland is potentially moving towards EU membership and in Greenland there is already a majority for rejoining is good, but Norway needs to get on board as well. Despite the positive momentum in EU–Norway relations, Norwegian politicians remain hesitant to take up the issue as the country is heading to elections in September 2025.

Just like in Finland and Sweden with NATO membership until 2022, in Norwegian politics there have been no points to be scored by advocating EU membership. Thus, all parties would benefit from the following recommendations:

1. Link the Nordic EU enlargement to Ukraine

Among the three prospective new EU additions, Iceland would be able to join the EU particularly fast. Iceland never formally withdrew its EU application, which means accession talks could be resumed swiftly from where they left off.

Norway, in particular, would have significant weight in the EU thanks to its role as Europe’s main gas supplier.9 But while the Nordic countries would be nice-to-have members, for Ukraine (and to an extent Moldova as well) the question of EU membership is existential. Despite the geopolitical urgency, Ukraine’s EU integration is bound to be a bumpy ride due to the impact its accession will have on the EU’s Common Agriculture Policy. By coupling Ukraine’s (and Moldova’s) accession to a Nordic enlargement round, the EU can change the narrative into a net positive one. Norway could especially tip the scale if it decided to link its accession to Ukraine’s.

2. The EU should make an offer that cannot be declined (and get over the fish)

As so often in the EU’s relations with coastal non-member European countries, the biggest issue between the EU and Greenland, Norway and Iceland is fisheries. Greenland left the EU due to the Common Fisheries Policy, in Iceland the fishing lobby is already mobilising against EU accession, and despite all the reasons to ensure that the EU and the UK are working closely together on defence, fisheries very nearly got in the way of a recent landmark agreement.10

Although fish is an easy emotional argument against EU membership, especially where coastal communities in Norway are concerned, the industry itself sees potential for a better fisheries deal through membership.11 Therefore, the EU should be forthcoming in proactively offering the prospective members a good deal on fish.

3. Norway needs to get the North on board

Support for EU membership has traditionally been an urban affair in Norway, with strongest opposition in rural parts of the country. Given the shifting geopolitical landscape and rising tensions in sparsely populated Northern Norway, driven by Russia’s increasingly reckless behaviour, it is imperative to highlight the benefits of EU membership for the region. Getting the northern regions to lead the debate on EU membership would turn the tables on the traditional yes and no camps.

Additionally, making Norway part of the same enlargement round as Ukraine would buy Norwegian politicians time for the domestic debate, as Ukraine’s EU integration process will inevitably take some years – and perhaps some good will from the voters who are strongly supportive of Ukraine.12

4. Nordic peer pressure to speed things up

In the Swedish NATO debate, one important argument was that if Finland was set on joining, Sweden could not remain the sole Nordic country outside of the alliance. Iceland moving towards EU membership could create similar momentum in Norway, especially if accompanied by a Greenlandic decision to rejoin the EU. While Norwegians remained negative towards EU membership despite Iceland’s integration attempt last time, the geopolitical situation has increased the urgency for the Nordics to stick together.

Denmark, Finland and Sweden can help by highlighting the possibilities alignment on EU membership would open up in the Nordic and Nordic–Baltic cooperation, drawing from the positive experience since Finland and Sweden’s NATO accession. The incoming Danish EU Council presidency could help nudge the process in Iceland, potentially creating some pull effect for Norway as well.

5. Timing is everything

Finally, initiating the EU accession process can open windows of opportunity for malign influence by foreign actors. Iceland has announced the intention to hold a referendum, and ‘yes or no’ referendum campaigns can easily be manipulated to polarise public opinion, as was the case in Moldova in 2024.13 The EU could help the Icelandic ‘yes’ campaign by signalling willingness to make a constructive offer, especially by addressing the concerns the energy and fishing lobbies are mobilising on.

In Norway, a debate on the complex issue of EU membership would ideally require a public information campaign as a first step. It is therefore best to save opening a discussion for after the September 2025 parliamentary elections, to prevent oversimplified and polarising positions from taking over the public discourse, and to allow citizens to make an informed decision if a referendum is to follow.

Greenland recently elected a new parliament, where cooler heads on the independence question prevailed. In Greenland’s case, it is particularly important to avoid framing EU membership as an alternative in opposition to Greenland’s current status or a closer relationship with the US. Rather, the EU should be presented as compatible with, and beneficial to, Greenland’s other geopolitical considerations.

Footnotes

1 ‘Nordmenn klare for ny EU-debatt’ [Norwegians are ready for a new EU debate], Opinion, 7 April 2024, https://www.opinion.no/innlegg/nordmenn-klare-for-ny-eu-debatt (accessed 27 May 2025).

2 Yeung, Jessie and Hudspeth Blackburn, Piper (2025) ‘Trump renews threat of military force to annex Greenland’, CNN, 4 May 2025, https://edition.cnn.com/2025/05/04/world/greenland-annexation-threat-trump-nbc-interview-intl-hnk (accessed 13 June 2025).

3 Dall, Anders (2024) ‘Måling: Grønlænderne er blevet mere positive over for EU’ [Poll: Greenlanders have become more positive towards the EU], DR, 30 December 2024, https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/maaling-groenlaenderne-er-blevet-mere-positive-over-eu (accessed 13 June 2025).

4 Marcus, Jonathan (2019) ‘Nato alliance experiencing brain death, says Macron’, BBC, 7 November 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50335257 (accessed 3 July 2025).

5 Tangen, Leslie and Lervik, Frank (2025) ‘Den islandske presidenten til TV 2: – Vi bør stemme over EU-medlemskap’ [The Icelandic president to TV 2: – We should vote on EU membership], TV 2 Norway, 10 April 2025, https://www.tv2.no/nyheter/innenriks/vi-bor-stemme-over-eu-medlemskap/17637825/ (accessed 27 May 2025).

6 Caulcutt, Clea (2025) ‘France floated sending troops to Greenland, foreign minister says’, Politico Europe, 28 January 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/france-fm-jean-noel-barrot-floats-sending-troops-to-greenland-denmark/; FRANCE24 (2025) ‘Macron arrives in Greenland to show solidarity for island coveted by Trump’, 15 June 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250615-macron-arrives-greenland-show-solidarity-island-coveted-by-trump (both accessed 16 June 2025).

7 Wulff Wold, Jacob (2025) ‘Norway-EU ‘situationship’ blossoms in face of tariffs, reforms’, Euractiv, 9 April 2025, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/norway-eu-situationship-blossoms-in-face-of-tariffs-reforms/ (accessed 27 May 2025).

8 See ARENA Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo (2024) ‘New EEA Study: A democratic problem that Norway has zero influence over EU regulations’ (interview by Gro Lien Garbo, with associate professor Guri Rosén), 24 April 2024, https://www.sv.uio.no/arena/english/research/news-and-events/news/2024/eos-utredning-.html (accessed 12 June 2025).

9 Eurostat (2025) ‘EU imports of energy products - latest developments’, (data from December 2024), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=674962#Main_suppliers_of_petroleum_oils.2C_natural_gas_and_coal_to_the_EU (accessed 27 May 2025).

10 Ross, Tim (2025) ‘UK-EU defense pact really does depend on fish, European minister warns’, Poltico, 25 March 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/uk-eu-defense-pact-really-does-depend-on-fish-european-minister-warns/ (accessed 27 May 2025).

11 Britto, Bethel and Strøm, Stian (2025) ‘Fiskeriministeren: – Jeg ønsker ikke en ny EU-debatt’ [Fisheries minister: – I don’t want a new EU debate], NRK, 25 March 2025, https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/fiskeriminister-marianne-sivertsen-naess-sier-nei-til-ny-eu-debatt-1.17349379 (accessed 27 May 2025).

12 Svendsen, Øyvind (2024) ‘Utenrikspolitiske holdninger i Norge i 2024: Status quo-folket i en internasjonal brytningstid’ [Foreign policy attitudes in Norway in 2024: A status quo people in an international turning point], NUPI report 6/2024, https://www.nupi.no/en/publications/cristin-pub/norwegian-public-s-attitudes-to-foreign-policy-in-2024-a-status-quo-nation-in-a-time-of-global-turmoil (accessed 27 May 2025).

13 Corman, Mihai-Razvan (2024) ’Three Takeaways from the Nearly Failed EU Referendum in Moldova’, Verfassungsblog, 1 November 2024, https://verfassungsblog.de/three-takeaways-from-the-nearly-failed-eu-referendum-in-moldova (accessed 25 June 2025).

The views and opinions in this brief do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.