This analysis explores whether and how mutually recognised quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs are creating enhanced trade benefits for third countries’ producer groups in the frame of the Common Market Organisation and Association Agreements of the European Union. A case-study on coffee protected by designations of origin in Central America.

Read all articles on CAP Strategic Plans.

1. Introduction

2. What are EU Quality Schemes for food, agricultural products and wines?

3. Current situation of the coffee sector in Central America

4. Central America’s Protected Designations of Origin in a nutshell

5. How are coffee quality schemes incorporated in the EU/CAP legal framework?

6. Main research findings

6.1. PDO coffee: multi-compliance vs economic returns

6.2. Unfinished commodity: processing and selling companies capture added value

6.3. The Tchibo-Marcala case

7. Conclusions and recommendations

References

1. Introduction

After more than 2 years of negotiations since June 2018, the three EU co-legislators[1] found an agreement on the regulations for the future Common Agricultural Policy post-2022 (CAP). Much of the attention is now moving on the 27 Member States who will be in charge of implementing these regulations via the future National CAP Strategic Plans 2023-2027.

The Common Market Organisation is one of the three regulations addressed by the CAP reform. It covers numerous crucial rules of agricultural markets at European and global scale, from the quality schemes to provisions concerning the reserve for crisis (market, climate, etc.).

In this article, we look specifically at the EU provisions on quality schemes from the perspective of small-scale coffee producers in Central America. Specifically, we explore whether and how the reform of the Common Market Organisation, intertwined with Association Agreements, has created the conditions to ensure and enhance trade benefits for producers in third countries.

Quality schemes like Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) play an important role in the future/ongoing CAP reform, and more broadly in the European Green Deal and its initiative on Corporate due diligence and corporate accountability. EU and non-EU quality schemes can be mutually recognized and protected by unlawful use. They can provide a higher degree of visibility for third countries’ agri-food products and, more importantly, could strengthen the producer groups’ position in the global value chain.

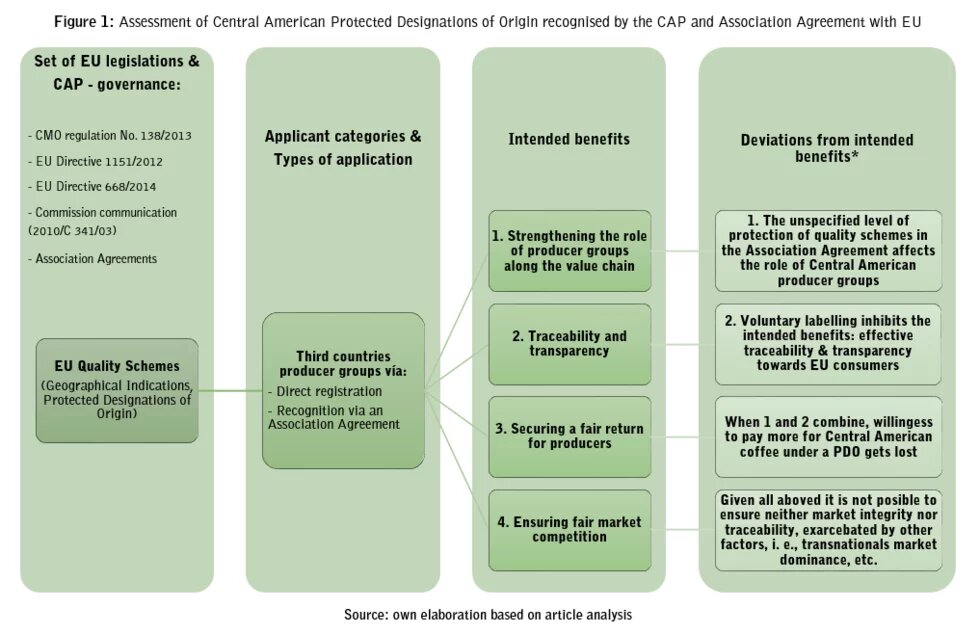

Quality schemes are intended to create multiple benefits for its holders. However, through in–depth interviews with the administrators of three of the five coffee protected designations of origin (PDO) in Central America, this analysis unveils how some EU legal and system loopholes (e.g. administrative and judicial steps) are weak in preventing the unlawful use of mutually recognized quality schemes, and ultimately impede coffee producer groups on the ground from receiving the expected trade benefits – specifically, in the context of the Association Agreement signed between both regions[2]. In contrast, our analysis presents the complexity of intellectual property rights’ assurance within the EU market from different angles.

2. What are EU Quality Schemes for food, agricultural products and wines?

EU quality schemes are official recognitions and registrations in a country to protect products’ established names and promote their unique characteristics linked to their geographical origin as well as traditional know-how. Quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs are widely used as enablers for economic added value and to ensure the protection of intellectual property rights. They were born under the Lisbon Agreement (1958)[3]. Straightaway, the EU actively promotes their recognition and usage, not just amongst European companies, but also in third countries.

For EU producers, Directive No. 668/2014 lays down the specific procedures for applying for quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs. Producer organizations outside the EU are also entitled to apply directly to the EU Commission for the recognition of a quality scheme in the EU internal market, independently of the existence of an Association Agreement.

Mutually recognized quality schemes, exercised in the negotiations and enforcement of bilateral/multilateral Association Agreements, have become part of the instrumentalization of the EU’s foreign trade policy. Every Association Agreement is negotiated individually, and intellectual property rights’ set of rules and dispositions may vary for every trading partner (country/region) (AIDA, 2012).

In the frame of Association Agreements, third countries’ producer groups must follow two steps to trade their products under quality schemes. Firstly, they must recognise their scheme in their own territory. Secondly, when the EU and third countries subscribe Association Agreements of bilateral or multilateral nature, these agreements usually include a clause on mutually recognized quality schemes.

It is important to stress that the level of protection of the mutually recognized quality schemes in the frame of an Association Agreement is negotiated and included in the Agreement dispositions (European Commission, personal communication, June 18th, 2021).

Therefore, these negotiated dispositions in Association Agreements put the provisions of the Common Market Organisation in second place and raises the need to envisage EU-wide harmonised rules that safeguard third countries producers’ intellectual property rights under quality schemes in both ways: via direct registration and recognition of schemes via Association Agreements.

3. Current situation of the coffee sector in Central America

Central America (CA) covers seven coffee producing-countries[4]. In 2020, the entire region accounted for approximately 14.5 % of shared value in world’s green coffee exports (Honduras: 5.8%; Guatemala: 3.5%; Nicaragua: 2.6%; Costa Rica: 1.8%; El Salvador: 0,6%; Panamá: 0,1%)[5]. Most of the coffee production in CA is largely cultivated by smallholders. On average, 87% of coffee farms in CA are less than 10 hectares size and are family-run farms (PROMECAFE/IICA, 2018). Out of its total coffee imports, the EU acquires 10.5% from CA.[6]

Even though CA is a prosperous area in terms of volume of coffee production, the lack of economic sustainability of the coffee sector starts with its profitability and poor economic returns. A regional macro-analysis reporting detailed costs of coffee production in the period 2016/2017 concluded that on average, the production costs of a coffee sack is around 181.00[7] EUR, without considering the smallholders costs occurred for the compliance (or lack thereof) to social conditionality standards. For instance, in Honduras, the official minimum wage in agricultural activities per day is USD 8.30; but coffee farm workers earn much less (Dietz, Grabs, & Chong, 2019). On average, smallholders receive export selling price of 120.53 EUR per sack, meaning a loss of approximately 63.26 EUR per sack. This demonstrates that coffee production is simply not lucrative for CA smallholders (PROMECAFE/IICA, 2018).

Besides the negative balance between production costs and selling prices, the economic sustainability of small-scale producers is penalised by an unfair supply chain governance strongly dominated by multinational companies operating in the international coffee trade (Grabs & Ponte, 2019) (DW, 2021). Companies such as Nestlé, Neumann Gruppe, Starbucks, and other trade giants are actively sourcing coffee across the region. Likewise, climate change has tremendously affected coffee production in CA. Adaptation strategies are urgently needed since climate change is rapidly affecting smallholders’ livelihoods in various ways, given that every coffee farm runs in different environmental ecosystems. Equally, dry season and rust disease outbreaks have exponentially increased production challenges (CIAT, 2018). Overall, coffee production is not a valuable livelihood strategy for many smallholders anymore. It is no surprise that small-scale farmers are falling into debt, putting their farms up as collateral to acquire some immediate cash to migrate illegally to the USA (DW, 2021) (REUTERS, 2019).

Considering coffee cultivation in CA is no longer profitable, the managing director of APCA Guatemala believes coffee cultivation underlies on a traditional basis, passed out through generations since coffee activities in the region are older than a century (Personal communication, May 07th, 2021).

4. Central America’s Protected Designations of Origin in a nutshell

When the Association Agreement with CA came into force (2013)[8], the EU subscribed 225 geographical indications from 19 Member States. Conversely, CA countries applied for the protection of 10 geographical indications, out of which five concern coffee harvested by smallholders’ producer groups. Their protection within the EU market started on August 5th, 2015[9].

Over the time, those geographical indications evolved into protected designations of origin (PDO), given the human factor associated with coffee producers’ groups and technical recommendations of local authorities’ specialists in intellectual property.

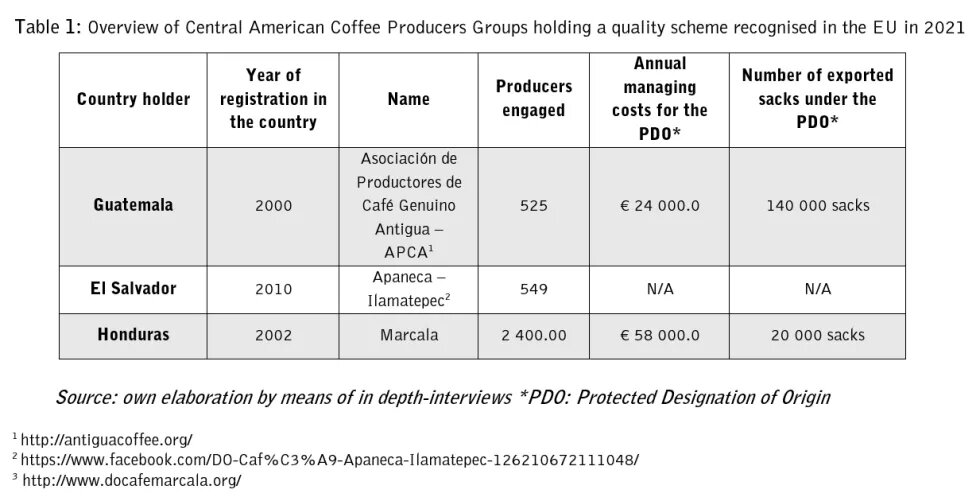

This analysis will only concentrate on three out of five coffee CA PDO. These are:

For international trade and export purposes, the CA coffee producer groups issue a certificate that states the coffee belongs to a PDO quality scheme guaranteeing unique coffee attributes.

The PDO disciplinary also establishes the standards for the roasting process for enhancing the coffee characteristics protected under the PDO. All CA producer groups who registered their coffee under the PDO disciplinary are engaged in coffee exports worldwide.

5. How are coffee quality schemes incorporated in the EU/CAP legal framework?

Geographical indications (GI), and PDO schemes in general, represent some of the EU market instruments aimed to enhance and differentiate the attributes and characteristics of agricultural goods. They intend to promote the association of an agricultural good with its origin (European Commission, 2021). At the point of sale, within the EU market and internationally, quality schemes intend to inform and guide consumers towards more conscious purchase decisions, with twofold intention: consumers get to know the origin of the product and increase their willingness to pay higher prices for it.

Although coffee is usually imported in the UE as green coffee, it is part of the CMO regulation No. 1308/2013. Coffee is included in Part I, Art. 2, incise x), Annex Part XXIV, under the Harmonized System coffee code 0901, covering all coffee product types. This implies that coffee is governed under the CMO regulation, as most of the agricultural products.

Once a third country form of quality scheme is incorporated into the EU either via an Association Agreement or direct registration, these schemes automatically enter in the EU market rules, including those of the CAP’s Common Market Organisation under the following set of rules/legislations:

- Art. 93(3) of the CMO Regulation No. 1308/2013 specifies that:

“Designations of origin and geographical indications, including those relating to geographical areas in third countries, shall be eligible for protection in the Union in accordance with the rules laid down in this Subsection”.

- The EU Directive 1151/2012 besides being specific on EU quality schemes, highlights the intended benefits for holders. Those apply also to third countries’ producer groups. The most promising are: “securing a fair return, ensuring fair competition, providing credibility in the consumers’ eyes and to those involve in trade, the role of producers groups might be strengthened”.

- The EU Directive 668/2014 lies down rules for direct application on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs.

- The Commission communication (2010/C 341/03) establishes voluntary guidelines on the labelling of foodstuffs using the schemes as ingredients.

- For this analysis, the title VI on intellectual property rights, section C of the Association Agreement between the EU and CA provides all legal dispositions which under both regions agreed the scope, coverage, and system of protection of EU quality schemes. Annex XVII contains the details of the mutually recognized quality schemes. Specifically, the dispositions on article 246 explain the protection granted.

On a supra national level, according to the EU Commission and the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO)[10] once a quality scheme from a third country is subscribed by direct registration:

“The level of protection of quality schemes by EU Regulations includes any direct or indirect commercial use of a name in respect of products not covered by the registration; any misuse, imitation or evocation, even if the true origin of the products or services is indicated or if the protected name is translated or accompanied by an expression such as ‘style’, ‘type’, ‘method’, ‘as produced in’, ‘imitation’ or similar, including when those products are used as an ingredient; any other false or misleading indication as to the provenance, origin, nature or essential qualities of the product and any other practice liable to mislead the consumer as to the true origin of the product. (EUIPO, personal communication, July 16th, 2021).

When the quality schemes from third countries are recognized in the negotiations of an Association Agreement the EU Commission as well EUIPO indicate that: “The EU aims at ensuring the level of protection similar to a direct registration, while the final outcome depends on each negotiation and could involve certain adaptations taking into account the specificities of the contracting party system” (EUIPO, personal communication, July 16th, 2021); which has been the CA case.

On a Member State level, according to Art. 13(3) of the Regulation 1151/2012, country-level authorities: “shall take appropriate administrative and judicial steps to prevent or stop the unlawful use of PDO”. This disposition should apply for PDO originating in third countries as well (European Commission, personal communication, June 18th, 2021), (EUIPO, personal communication, July 16th, 2021).

6. Main research findings

For understanding to what extent, the CA coffee PDO have “secured a fair return, ensured fair competition, gained credibility in the consumers’ eyes and strengthened the role of producers (smallholders)” within the EU market, by means of in depth-interviews, the administrators of the PDO showcased in Table 1, were interviewed. Therefore, the results portray the status quo of the aforementioned and intended benefits of quality schemes.

6.1. PDO coffee: multi-compliance vs economic returns

As part of the export transaction, CA coffee producer groups offer their customers a certificate that guarantees the exact origin of the coffee using the PDO scheme. According to Marcala PDO, this certificate allows them to reach a higher selling price, estimated on an average of an extra EUR 45.19 per green coffee sack compared to world market prices (Personal communication, May 04th, 2021).

However, when revisiting the fact that the coffee value chain in CA lacks economic profitability, with a loss of approximately EUR 63.26 per sack, albeit producer groups holding a PDO quality scheme receive an average of EUR 45.19 more per sack (Personal communication, May 04th, 2021), financial loss is still persistent. Therefore, PDO holders still operate under earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) with no revenue. This means smallholders perhaps manage to cover their operation costs but are not able to accumulate further earnings. In addition, producer groups make high investments to maintain the PDO standard itself (PDO managing costs showed in table 1). And, in most cases, smallholders’ producer groups comply with other private certification standards.

Overall, even though CA smallholders comply with a PDO scheme, the further price mark-up resulting from its compliance, only serves as a financial incentive that assures the PDO continues functioning.

6.2. Unfinished commodity: processing and selling companies capture added value

The primary motivation for third countries’ negotiating an Association Agreement is to achieve better market access conditions. Certainly, mutually recognized quality PDO become foreign trade enablers for product differentiation. For the CA subscribed PDO showed in table 1, the intended benefits of a PDO have not been fully achieved so far, even seven years after the protection granted by the Association Agreement has entered into force.

The primary constraint in the coffee export business is the fact that this is exported as raw material and not as a processed good. This in turn enables and maintains an unfavourable trade situation: CA green coffee tends to become an ingredient which, after the export/import processes, just becomes part of a roasted coffee brand. Once the coffee is roasted, the origin, the terroir, and PDO established name tend to become invisible to consumers’ eyes. A proper intellectual property rights exchange (in form of a contract or other legal mechanism) between producer groups and EU importer/roasters is non-existent.

There are many reasons behind it. The first are labelling rules. The second is the use of green coffee for commercial coffee blends. The third is the lack of harmonised mechanisms to monitor how the intellectual property rights are respected across the EU market. This might have helped CA coffee farmers to trace and track where their coffee is finally sold and under which brand name their PDO is showcased.

In the first case, despite the intellectual property rights conferred to the producer groups through the PDO quality scheme, referred to Art. 13(1)(a) of the Regulation 1151/2012, the uptake of the EU Commission guidelines on the labelling of foodstuffs that are using PDO or protected geographical indications (PGI) as ingredients (2010/C 341/03) remain voluntary for EU traders and roasters. The practical implication of these dispositions is that an EU consumer cannot know that the coffee comes from a third country PDO. Moreover, according to the EU Commission, the original PDO name used as ingredient might be included in the final version of the manufactured coffee when: “By way of exception only in order to resolve a specific, clearly identified difficulty and provided they are objective, proportionate and non-discriminatory" (European Commission, personal communication, June 18th, 2021). In that sense the CA PDO have not gained further credibility in European consumers’ eyes, because the likelihood the name of any CA coffee PDO appears in a roasted coffee brand packaging is low/random/unknown.

Concerning the second reason, the protected characteristics of a coffee under a PDO scheme definitively get lost when this coffee is used for commercial blends. It happens to the coffee from the PDO Marcala: “Most of our coffee really goes for blends, so they do buy our green coffee with the certificate, because they always want to guarantee the same cup profile and the same quality with coffee from Marcala” (Personal communication, May 04th, 2021). This finding is consistent with the case of Coffee of Colombia under the EU’s latest assessment on quality schemes (European Commission, 2020).

It is imperative to realise that, when the first and the second situations happen, there is neither the possibility of providing information to consumers about the true origin of the coffee nor the possibility of engaging consumers’ willingness to pay higher prices for coffee originating from a CA PDO. Therefore, the intention that agricultural quality schemes intend to enhance and differentiate the attributes and characteristics of agricultural goods linked with their origin; and aim to secure higher/fair returns farmers, remain unrealised.

The third aspect refers to the lack of an institutionalized monitoring system that helps smallholders in CA understand how to assure their intellectual property rights in the frame of an Association Agreement in 28 countries. It was explicitly expressed by every representative of the CA PDO:

APCA: “In an international market, we have no way to control or measure the use of our PDO in foreign markets. We as an association issue a certificate that is endorsed with a coffee - taste/cupping quality control, thus we can guarantee it is a genuine Antigua – APCA coffee, we take care of all quality aspects in the delivery process. Nevertheless, we have not an infrastructure abroad that supports us to manage the controls and quality of our coffee once it has been exported” (Personal communication, May 07th, 2021).

MARCALA: “There is no monitoring procedures at the international level, it is more a job we conduct of digital supervision of social networks. It is a process of digital surveillance. If something comes up, we try to communicate with companies selling Marcala coffee without an agreement with us. At the national level we do have a monitoring procedure, but internationally, we really don't have one” (Personal communication, May 04th, 2021).

APANECA-ILAMATEPEC: “From far away, and only having contact with a buyer once a year, it is not possible to understand where our coffee is going” (Personal communication, June 04th 2021).

All the representatives of the CA coffee PDO appeal for a monitoring mechanism within the EU market that signals where their PDO certified coffee is finally roasted and sold. This mechanism should be created and enforced in a way that the intellectual property rights of a PDO encompasses both - rights’ assurance and traceability. Were this in place, this would finally help Global South coffee producers to realise the economic added value generated by the schemes within the EU market. In the same fashion EU producers have gained a clear overview of the scheme´s enhanced benefits[11].

Altogether reasons and preceding the next subsection, the following case exemplifies the combination of all situations, and it shows how a smallholder coffee producer group from a third country cannot benefit from the PDO scheme.

6.3. The Tchibo-Marcala case

An in-depth interview with Marcala revealed that the German multinational coffee company has used Marcala’s name without consent, despite its name is being protected at the EU level[12]. There have been two incidents, the first dating back to 2017 (https://blog.tchibo.com/aktuell/land-der-tiefen-gewasser-und-ursprung-unserer-neuen-limitierten-kaffees-marcala/) and the second, where the multinational offers coffee capsules with Marcala’s coffee as an ingredient (https://www.tchibo.de/neu-grand-classe-espresso-marcala-honduras-80-kapseln-p400121599.html). Marcala’s PDO administration has no means of proof whether the coffee used in Tchibo products is manufactured exclusively with their coffee or is a blend.

The managing director of Marcala assures the farmers presented in Tchibo’s advertisements neither belong to the rural area that encompasses the PDO, nor are members of the PDO. After visiting Tchibo’s domain, it is clear, that the PDO as a quality scheme does not figure.

After an e-mail inquiry, Tchibo did not want to provide a statement regarding their willingness to comment on the cases. Since the EU Commission granted the protection on August 2015, Tchibo should have taken into consideration the PDO status (Personal communication, May 26th, 2021). What is more, in further consultation with the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DPMA[13]), the entity answered they are neither in the position to comment on the case nor to advise what procedures are adequate to clarify the scope of intellectual property rights obligations for both parties (Personal communication, May 10th, 2021). In further communication with the Hamburg chamber of commerce[14], such case cannot be solved under arbitration or conciliation procedures (IHK-Hamburg, personal communication, July 15th, 2021).

Marcala’s PDO administration body has asked Tchibo directly for plausible explanations on both cases, without success (Personal communication, May 04th, 2021).

According to the EU Commission two possible solutions for this case are: either to submit a complaint via Honduran authorities to the EU Commission or use the German judiciary system. (European Commission, personal communication, June 18th, 2021), (EUIPO, personal communication, July 16th, 2021).

But how much time, financial resources, assessments, and procedures might such a claim involve? Can a smallholder groups endeavour an intercontinental legal battle against a multinational? Shouldn’t the EU regulation envisage the right tools and mechanisms to safeguards their own consumers, as well as third countries producers’ rights?

Figure 1 gives a synthetic overview of the main research findings.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

To ensure the effective achievement of quality schemes’ intended benefits for third countries’ producers, EU and non-EU legislators and trade operators can work together in different areas: 1) monitoring systems to respect the compliance with intellectual property rights; 2) integrate quality schemes into transnational associations of producers organisations under the CMO; 3) upgrading of official portals; 4) streamlining and regularising procedures for the quality schemes application and mutually recognition, and more.

In this section, we present some considerations on how to align the interests of Global South, and especially CA, coffee producer groups with the purpose of assuring trade benefits derived from the quality schemes.

- Visibility in the market & visibility for EU consumers

It is true that through the recognition of quality schemes, holders can achieve better supply chain organization. In the context of Association Agreements’ negotiations for achieving better market access however, so far it has not been possible for CA recognized coffee PDO schemes to have a clear overview of their participation in the EU coffee market. One of the latest assessments conducted by the European Commission concludes that due to low market share/sales of agricultural products from third countries, it is impossible to measure the impact of the EU quality schemes (European Commission, 2020).

But the CA coffee PDO suppliers challenge this finding by signalling EU directives are not specific enough to operationalize the quality schemes' rights assurance. When the labelling of a PDO green coffee used as an ingredient remains voluntary for EU food business operators, traceability, and transparency, especially at the vital consumer end, is lost. Intellectual property rights cannot be safeguarded. Consequently, market share cannot be calculated by third country producers.

Labelling norms, besides becoming mandatory, should provide specific dispositions for presenting the PDO features of agricultural goods as its participation as an ingredient in the final product. For the coffee case, should a coffee blend contain a percentage of a PDO coffee from the Global South, it must be explicitly stated in the packaging. Of course, in agreement with the producer groups. Then the premise of providing credibility of the true origin of the product as an enhanced benefit of a PDO schema will be accomplished.

- Introducing IP monitoring systems via official EU IP portals for gaining market share accountability

Certainly, for both, EU and non-EU holders, information on all protected quality schemes is available at the official databases eAmbrosia[15], and Geographical Indications view from EUIPO[16]. However, it is unknown to what extent an official online available register effectively communicates the intellectual property rights’ provisions for EU companies trading with third countries’ holders of quality schemes and the contractual obligations for both parties. As part of legislations reforms, the upgrading of official portals is desirable (Regulation 1151/2012, Art. 11). For example, these portals could include guidelines on the intellectual property rights of non-EU holders' schemes when commercialized within the EU market and could contain a mandatory register for EU traders when commercializing agricultural products from third countries that possess a recognized quality scheme and are used as ingredients (such as coffee, cocoa, etc.). The later might be a desired monitoring mechanism that could help producer groups from third-countries understand how an agricultural foodstuff used as ingredient transforms into an EU brand and where it is finally sold. This form of accountability, again will challenge the latest EU analysis: …”that due to a low market share/sales of agricultural products from third countries, it is impossible to measure the impact of the EU quality schemes (European Commission, 2020).

- Global South producer groups participation in EU interbranch organisations

It is not a requirement for third countries’ producer groups to have an office or a legal representative in the EU to accede to an EU quality scheme. But the EU Commission could consider other mechanisms safeguard their rights, such as recognizing and granting support to third countries’ producer groups and their participation in interbranch organizations within the EU[17].

In the negotiations about the future Common Market Organisation in the EU, transnational producer organisations are recognised, although there are little to no provisions for those originating in third countries. The new reform might integrate EU quality schemes into producers’ organisations under the CMO, however, third countries’ producer groups were not considered at any stage (European Parliament, 2020).

- Improvement of the CMO regulation

The position adopted by the European Parliament on the CMO in October 2020 strongly emphasized the streamlining of EU quality schemes’ application procedures, and other administrative procedures applying to the schemes’ rules. In particular, amendment 25(h), promotes the collaboration of Member States and intellectual property authorities in third countries; but this reform fails to specify whether the scope of this collaboration should happen on a regular basis (institutionalized) and to what extent mutually recognized schemes need a systematic evaluation on their performance in the markets.

On the other hand, while developing this analysis, the only available source of information is the European Commission. Overall, as the “Evaluation support study on Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed protected in the EU” suggests, the Commission should endeavour closer cooperation with authorities in third countries and find synergies for achieving proper enforcement of the schemes and combat deficiencies as the Marcala-Tchibo case (European Commission, 2020). Generally, because the magnitude of intra-trade operations within the EU market, future CMO agreements should consider the incorporation of a subsection and set of legal dispositions that clearly define and safeguard the scope of third countries producer groups’ rights within the EU market.

- Upgrading the IP rights of the Association Agreement between CA and the EU

With this in mind, seven years after committing for PDO protection under the Association Agreement with the EU, it is not possible for CA coffee producers to assure the integrity of an internal market within the EU, or to present the value-adding characteristics of the coffee and its “terroir” to European consumers. Henceforth, the degree of protection of EU quality schemes specified in Art. 246 of the association agreement between both regions needs to be significantly improved. Especially, when the aforementioned aspects have not been taken into consideration.

- Policy coherence with future legislation

The first section of this analysis presents CA smallholders in the coffee sector face several challenges. Sadly, the official report on the Profitability of the coffee sector in CA[18], on pages 53 and 54, exposes forms of labour exploitation portraying minors working as coffee farm operators and inadequate forms of coffee transportation. Local newspapers present children picking coffee as well[19]. Notably, the EU initiative on corporate due diligence and corporate accountability legislation should become a mechanism to improve the welfare situation of producer groups in the Global South precisely to avoid what is to see in the media.

Nevertheless, as the EU Commission recommends in disposition 34[20] as a framework of this legislation: “…Third-party certification schemes can complement due diligence strategies, provided that they are adequate in terms of scope and meet appropriate levels of transparency, impartiality, accessibility, and reliability…”.

This is not entirely applicable to the CA coffee sector. The findings of the research: “Mainstreamed voluntary sustainability standards and their effectiveness: Evidence from the Honduran coffee sector”, and “Additionality and Implementation Gaps in Voluntary Sustainability Standards”, conducted by (Thomas Dietz, 2021) and (Dietz, Grabs, & Chong, 2019), suggest that despite the use of third-party certification systems, the hiring of minors still persistent and private standards cannot always be fully adopted by smallholders. In addition to these research projects, there are recurrent findings of children working in coffee farms across CA. In Guatemala child labour has been found in farms that supply Nestle. (REUTERS, 2020), the DW also filmed children picking coffee in Honduras (DW, 2021).

The set of legislations supporting quality schemes for agricultural goods should be upgraded and include stringent labour protection dispositions coupled with the compliance of any type of them. Especially, for the case of PDO and its human factor associated with production practices. Since the registration/recognition of the scheme against the EU Commission provides a direct link with the origin of the agricultural goods. It could also provide immediate accountability about the social conditionality standards behind any agricultural supply chain pursuing a PDO/GI.

Recent agreements (2021) on regulation 1151/2012[21], article 5, paragraph 1, section b) fail to address labour standards and limits itself to the following provision: “whose quality or characteristics are essentially or exclusively due to a particular geographical environment with its inherent natural and human factors; and…” but Is it possible to continue importing global south PDO green coffee into the EU knowing there are many children involved in the picking process?

All things considered, coffee is an important commodity and worldwide constitutes the livelihood of many smallholders in the Global South, including CA. When the EU’s legal framework is not associated with further rights improvements for third countries’ producer groups, the intended benefits of EU quality schemes are unreachable.

This article was first published by Arc2020.

AIDA. (2012, December). Rivista di diritto alimentare. Retrieved from Associazione Italiana di Diritto Alimentare – AIDA: http://www.rivistadirittoalimentare.it/rivista/2012-04/OCONNOR.pdf

Areté Research. (2013, December). Assessing the added value of PDO/PGI products. Retrieved April 10th, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-ag…

CIAT. (2018, June 14). Research program on climate change, agriculture and food security. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from The impact of climate change on coffee production in Central America: https://ccafs.cgiar.org/publications/impact-climate-change-coffee-produ…

Dietz, T., Grabs, J., & Chong, A. E. (2019, February 28). Mainstreamed voluntary sustainability standards and their effectiveness: Evidence from the Honduran coffee sector. Regulation & Governance. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12239

DW. (2021, February 11). DW | Actualidad | Economía. Retrieved from El amargo negocio con el café: ¿Quiénes ganan de verdad?: https://www.dw.com/es/el-amargo-negocio-con-el-caf%C3%A9-qui%C3%A9nes-g…

European Commission. (2008, November). Evaluation of the CAP policy on protected designations of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indications (PGI). Retrieved April 5th, 2021, from European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/ke…

European Commission. (2012, June 29). Comprehensive Association Agreement between Central America and the European Union. Retrieved September 16, 2020, from Press Corner: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_12_505

European Commission. (2013, December). Assessing the added value of PDO/PGI products. Retrieved April 10th, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-ag…

European Commission. (2019, January 01). Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products. Retrieved September 28, 2020, from EUR - Lex: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02013R1308-20…

European Commission. (2020, December). Evaluation support study on Geographical Indications and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed protected in the EU. doi:10.2762/891024

European Commission. (2021, April 30th). Quality schemes explained. Retrieved from EU - Food, Farming and Fisheries: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/food-safety-and-qualit…

European Parliament. (2020, October 9). Common agricultural policy – amendment of the CMO and other Regulations. Retrieved May 15, 2021, from Texts adopted - Procedure : 2018/0218(COD): https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0289_EN.html

European Union. (2012, June 06). Agreement establishing an Association between the European Union and its Member States, on the one hand, and Central America on the other. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from European Comission: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:22012A1215(01)

European Union. (2012, June 06). EUR-Lex. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from European Comission: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:22012A1215(01)

Grabs, J., & Ponte, S. (2019). The evolution of power in the global coffee value chain and production network. Journal of Economic Geography, 803 - 828. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbz008

London Economics & ADAS and Ecologic. (2008, November). Evaluation of the CAP policy on protected designations of origin (PDO) and protected geographical indications (PGI). Retrieved April 5th, 2021, from European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/food-farming-fisheries/ke…

PROMECAFE/IICA. (2018, March). El estado actual de la rentabilidad del café en Centroamérica CABI. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from Publicaciones PROMECAFE: https://promecafe.net/?p=5405

REUTERS. (2019, September 19). Honduras coffee exports to fall as farmers' plight deepens - industry. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/honduras-coffee/honduras-coffee-exports…

REUTERS. (2020, March 26). Nespresso finds child labor at three Guatemalan coffee farms. Retrieved from Reuters-News: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-guatemala-trafficking-coffee-trfn-id…

Salvadorian Coffee Council. (2020). Denominaciones de origen, protección a la calidad vinculada a su origen. San Salvador, El Salvador.

Thomas Dietz, J. G. (2021, February 16). Additionality and Implementation Gaps in Voluntary Sustainability Standards. New Political Economy, pp. 1-22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1881473

[1] EU co-legislators are the European Commission, European Parliament, and the Council

[5] www.trademap.org (HS 090111)

[7] https://www.ofx.com/en-au/forex-news/historical-exchange-rates/yearly-a… (1.10656) | Exchange rate applies for all EUR prices mentioned along the document