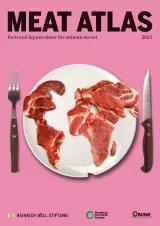

The Association Agreement between the European Union and the Mercosur countries raises concerns with regards to meat and feed, as well as the rainforest and the climate. But the EU is worried about cheap imports, and resistance is growing. Whether the deal will actually come into force is questionable.

It took more than 20 years for the European Union and the Mercosur countries – Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay – to negotiate an agreement for their two economic areas. The draft deal envisages eliminating customs duties, after a transitional period, on 92 percent of imports from Mercosur to the EU, and on 91 percent of the trade going in the opposite direction. That would greatly ease the export of agricultural products such as ethanol and beef from South America, and of items such as vehicles, machinery and chemicals from Europe to the Mercosur states. If the agreement is approved by the Council of the European Union, then the European Parliament and the parliaments of EU member states, as well as the governments of the Mercosur countries, will also have to give their consent before it can come into force.

Between 70 and 80 percent of all beef imports in the EU currently come from Mercosur. The agreement would expand this. On top of the 200,000 tonnes of beef that enter the European Union from the area every year, another 99,000 tonnes could be imported with zero or minimal customs duties. The Sustainability Impact Assessment, published by the EU in July 2020, forecasts that beef imports will rise by 30 to 64 percent under the individual provisions. In a study of its own, the French government calculates that the facilitated market access for beef from Mercosur could increase deforestation there by at least 5 percent a year over a period of 6 years. Those are far-reaching consequences, even though beef exports to the EU are a relatively small part of total production in Mercosur – which exceed 11 million tonnes of liveweight and 7.8 million tonnes of carcass weight a year.

Beef is already one of the main drivers of deforestation today. It leads to the destruction of the livelihoods of indigenous and small-scale farming communities. In the Amazon, cattle graze on 63 percent of all deforested land. Half the agricultural products shipped from Brazil to the EU – mainly soybeans, beef and coffee – can be traced back to deforestation.

Exports of poultry and pork would also increase as a result of the agreement. Some 180,000 tonnes of poultry meat per year could be imported into Europe duty-free, on top of the 392,000 tonnes allowed today. Another 25,000 tonnes of pork would be added at a low-tariff rate. This would nearly double the EU’s pork imports from Mercosur, which currently total around 33,000 tonnes a year.

Similar predictions have been made for soybeans, which are used mainly as livestock feed in the European meat industry. Brazil is the world’s biggest soy exporter. The EU’s Sustainability Impact Assessment predicts that imports of soybeans and other oilseeds from Mercosur could rise by up to 5.9 percent, with serious ecological consequences. According to a 2019 study, almost two-thirds of the pesticides sold in Brazil are applied in soybean and sugarcane cultivation. The deal with the EU would eliminate duties on pesticides imported into Mercosur, which may now be as high as 14 percent. Trade in pesticides would be strengthened, to the benefit of the European and especially the German chemical industry.

The EU–Mercosur agreement would not only have a negative impact on forests and biodiversity in parts of South America. It would also harm the climate. More carbon dioxide would be emitted because of further deforestation and increased production and transport. The French impact assessment even shows that under such conditions, the production of a kilogram of beef is responsible for four times the greenhouse-gas emissions as the equivalent in Europe.

It is not yet certain that the agreement will actually come into force. The amount of criticism is too great. Farmers in Europe fear that they will not be able to compete because of falling prices. Non-governmental organizations criticize the preferential treatment given to pesticide exports, as well as the consequences for the climate. More and more EU member states are also expressing scepticism or even criticism. In France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland and Austria, governments and parliaments agree that the agreement cannot be ratified in its current form. The German chancellor has also expressed concerns.

In a non-binding resolution, the EU Parliament voted for changes. The EU Trade Commissioner, Valdis Dombrovskis, has stated that the agreement would not be reopened and renegotiated. Amendments would be limited to protocol annexes, roadmaps and similar details. This has been the case for other EU agreements. The ratification process has already been put on hold until after 2021. But that does not mean it has been put on ice, as Bernd Lange, Chair of the EU Parliament’s Trade Committee, has emphasized.