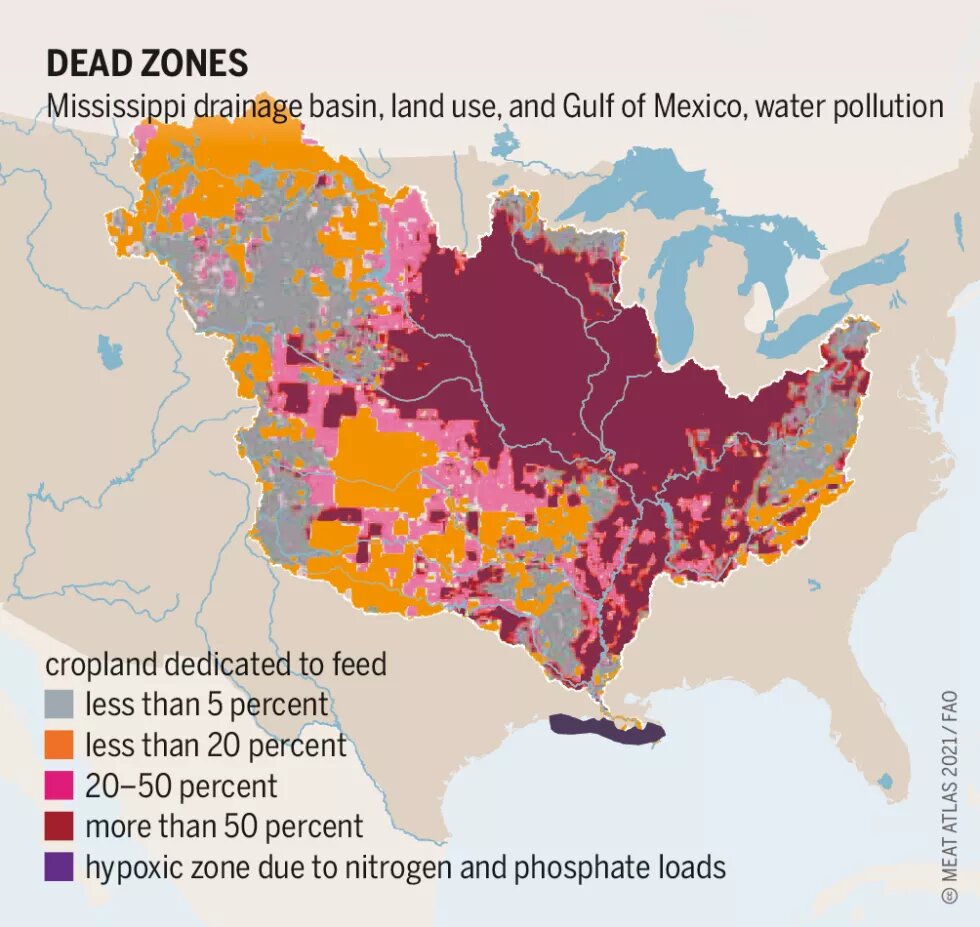

Nitrogen pollution from livestock manure is an increasing problem in many parts of the world. Countries in the European

Union have lots of ideas on how to reduce such contamination of their environments. One approach is through closer monitoring of industrial livestock producers and restricting the amount of manure slurry that crop farmers are allowed to apply.

Rivers, streams and lakes in many parts of Europe are polluted with nitrogen. One of the main causes is industrial livestock farming, which produces large amounts of slurry and manure which are used as fertilizer for crops. The nitrogen they contain is a nutrient that plants need to grow. But if too much is applied, it leaches down into the soil. Under unfavourable circumstances, it can end up as nitrates in the groundwater and ultimately in the sea.

The less nitrogen that the manure releases into the environment, the greater its value as a fertilizer, and the less of a threat it poses to water bodies. Optimal fertilization depends heavily on the timing and on the methods used. The loss of nitrogen into the atmosphere in the form of ammonia gas can be reduced if manure tanks are covered, or if the slurry is worked into the ground immediately after it is spread on a field. In standing crops, this is best done by injecting it into the soil rather than spreading it broadly on the surface. Farms that use the right techniques can significantly reduce their losses.

In practice, animal manure is not regarded as an adequate fertilizer to fulfil the plant demand in intensive production. Mineral fertilizers are therefore also applied to fields. This can also lead to excessive nitrogen loads that can contaminate the groundwater. The European Union’s Nitrate Directive currently specifies a limit of 50 milligrams of nitrate per litre of drinking water, and a guideline value of a maximum of 2.8 milligrams of total nitrogen in surface water.

The EU’s legal maximum total nitrogen level for animal manure is 170 kilograms per hectare. Applications of mineral fertilizers add to the amount of nitrogen. In many European countries, more than 100 kilograms of nitrogen surplus is spread on fields each year, exceeding the maximum and guideline levels for nitrates in groundwater. This is especially the case in regions with intensive livestock farming practices. Denmark, Germany and the Benelux countries, with their high concentrations of livestock, are particularly affected. They have had to take decisive countermeasures and adapt their regulations in recent years in order to comply with EU agricultural and environmental policies.

In Denmark, where export-oriented animal production is an important sector in the economy, the authorities have been taking effective action since 1985. Nitrate concentrations that sometimes exceeded 200 milligrams per litre in soil layers near the groundwater level have been halved over the past 10 years. Farmers are now obliged to keep digital records of their fertilizer plans. These plans must be based on the expected yield levels and had to be 10 to 20 percent below the calculated economic optimum until 2015. Spreading slurry in autumn, after the main harvest, is largely prohibited because the plants need scarcely any nitrogen then. These restrictions have triggered a comprehensive modernization of the machinery and equipment fleet in order to incorporate the manure effectively into the soil.

The use of low-emission application methods is now mandatory in many countries in western Europe, such as Belgium, Denmark and the Netherlands. This has also been true for arable land in Germany since 2020, but will not apply to grassland until 2025. To prevent an unchecked increase in livestock farming on vulnerable soils, the Netherlands imposes regional limits for the amount of manure that may be applied. If the amount per hectare is too high, the manure must be separated into solids and liquids at a separation plant. The manure can then be more efficiently exported to regions with fewer livestock and used in crop farming outside the country, if necessary.

In addition to capping the amounts of fertilizer, it makes sense to adjust how crops are grown. In Denmark, a minimum of six percent of the agricultural area must be devoted to “catch crops”. These are crops that bind nitrogen in their biomass over winter and prevent it from being leached away. Depending on the cultivation system, legumes can be used as a catch crop to a certain extent. Legumes are plants whose roots host symbiotic bacteria that are able to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere. This enables the farm to avoid the need to apply additional synthetic nitrogen that would have to be produced in an energy-intensive way.

Other options open to farmers include “precision farming” techniques, and shifting the winter sowing of grains to as early a date as possible. Precision farming methods include using special sensors in the field in order to apply an amount of fertilizer that meets the plants’ precise requirements. Sowing earlier allows the plants to take up more nitrogen before the winter months. No matter the approach, it is necessary to monitor performance with the help of farm data. In Denmark, exceeding the legal limits for nitrogen incurs a levy of at least 1.30 euros per kilogram. In additional to regulations, many EU countries offer free advice to farmers on how to protect water. Starting with a fairly high level compared to other European countries, the Netherlands has been able to cut its applications of mineral fertilizer by 50 percent since 1990.

Despite such successes, official support for voluntary measures will lead to marked improvements only if protecting the environment pays off for livestock farmers and if they can factor it in over the long term. From the point of view of water protection, environmentally friendly livestock production can succeed only through policy instruments. Those include capping the surpluses of nitrogen and phosphorus that a farm is allowed to produce, and reducing EU agricultural subsidies for farms that exceed the limits.