Digitalisation has already changed urban micro-mobility. The next step is the development of a single app for all mobility services.

The ongoing transitions in the automotive sector and in the new emerging mobility alike rely on hyper-connectivity via the internet of things (IoT), which means an interconnectedness of tools and services.

Car ownership in the EU-28 area increased considerably between 2000 and 2017, growing from 411 cars per thousand inhabitants to 516. However, the industry is now expected to reduce its carbon emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. The question remains whether the classic fossil-fuel car will be replaced by another service or another type of car, either electric, powered with hydrogen, leased or as a service, whether public, private or collaborative.

A new emerging and connected mobility is changing the urban micro-mobility: bikes, shared bikes, e-scooters, for passengers and for the delivery of the last miles, ride-sharing, car-sharing, either in parking or in free-floating. They have changed short-distance journeys in the city centres and, above all, have revolutionised trips from suburbs to city-centres and inter-suburb journeys, thereby offering a new territorial network.

All these highly-connected business-to-consumer (B2C) services are developing apps in order to connect service providers with clients. The inflation of apps is an issue for service providers. In particular, independent private chauffeurs and messengers have to work on several platforms at the same time if they want to have access to a higher demand.

The social impact of this transition is important. Platforms such as Uber only provide the software for independent drivers, who cannot rely on any basic income.

To counterbalance this phenomenon, aggregation of services is most likely to be the next step of the mobility revolution. This new reality falls under the definition of Mobility as a Service (MaaS). MaaS aims to create a simplified and unique marketplace where many mobility services will be offered through a single app or equivalent. According to a recent survey, 59 percent of Europeans are interested in using a MaaS-type app. A few stakeholders dominate the MaaS-market: the car industry, big tech companies, transportation companies and public authorities. They all wish to be the unique marketplace for mobility.

The internet of things is fuelled by data, from both service-providers and customers. As a consequence, data interfaces and ownership are key political issues. Anonymous data concerning mobility might reveal the identity of their owner, as they might show a pattern that can easily be tracked.

Autonomous driving is one of the big question marks in the picture. If successfully applied on a larger scale, it will revolutionise the mobility sector (from private cars to the logistic chain) in the next ten years. In view of the technological costs and the amount of data and energy needed to power a vehicle, they will have to be shared and on demand. Based on this assumption, the future of private cars, but also taxis, ride-hailing, metros, tramways and mass transportation, is uncertain.

Transportation, sharing and the collaborative economy were not prepared for a global health crisis that recommends social distancing for all. Uber and BlaBlaCar will have to overcome consumers' misgivings over sharing the same air in a small and confined vehicle.

If the years to come were expected to bring a shift from a highly carbon-consuming, expensive, inefficient transport sector to a low-carbon, inclusive, safer, connected service, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought some uncertainty to this development.

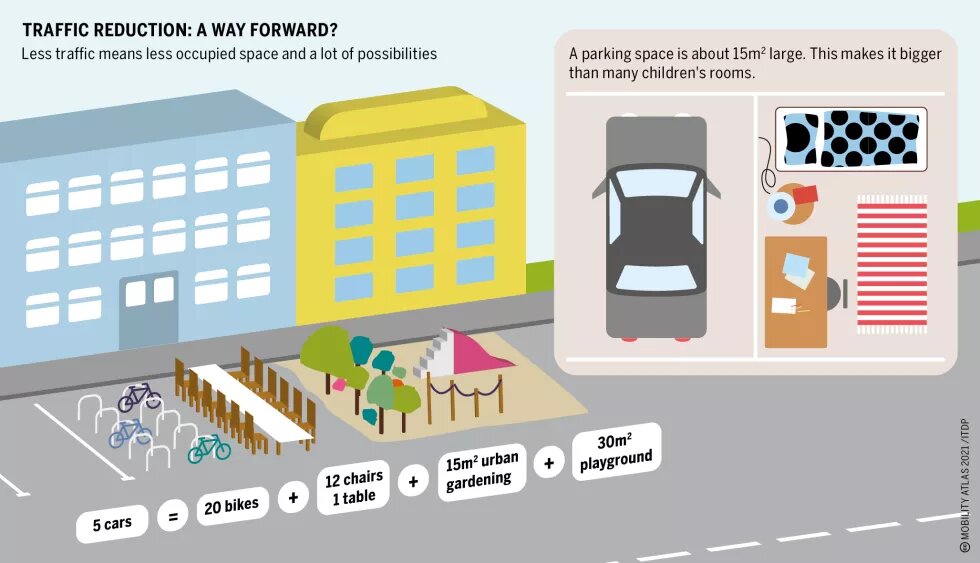

Sources for data and graphics: Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, Sizing Up Parking Space, https://bit.ly/3jF6W2c; ADEME Presse, Quelle stratégies des européens pour leurs mobilités?, https://bit.ly/2HHEvUn; The International Association of Public Transport, Mobility as a Service, p.2, https://bit.ly/2TUXQUP