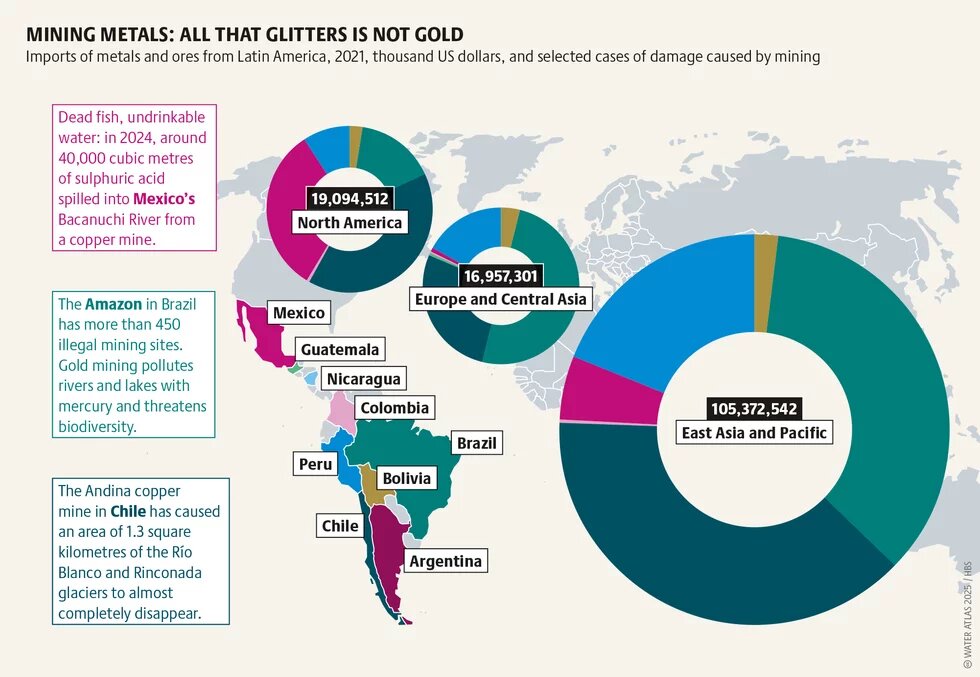

In Chile and elsewhere, multinational mining companies destroy glaciers and displace Indigenous Peoples. With raising demand for minerals there is an increasing threat of resource conflicts because of mining’s thirst for water and its huge impact on water quality. A circular economy is one way to slow down the rush to dig up the ground.

Metals such as copper, aluminium, lithium, rare earths, and gold are a big part of our daily lives. They are found in everything from infrastructure projects, the energy sector, transport and housebuilding. And in our pockets: an average mobile phone may contain up to 66 different metals, according to Germany’s Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. Precious and specialist metals in particular are vital to make them work.

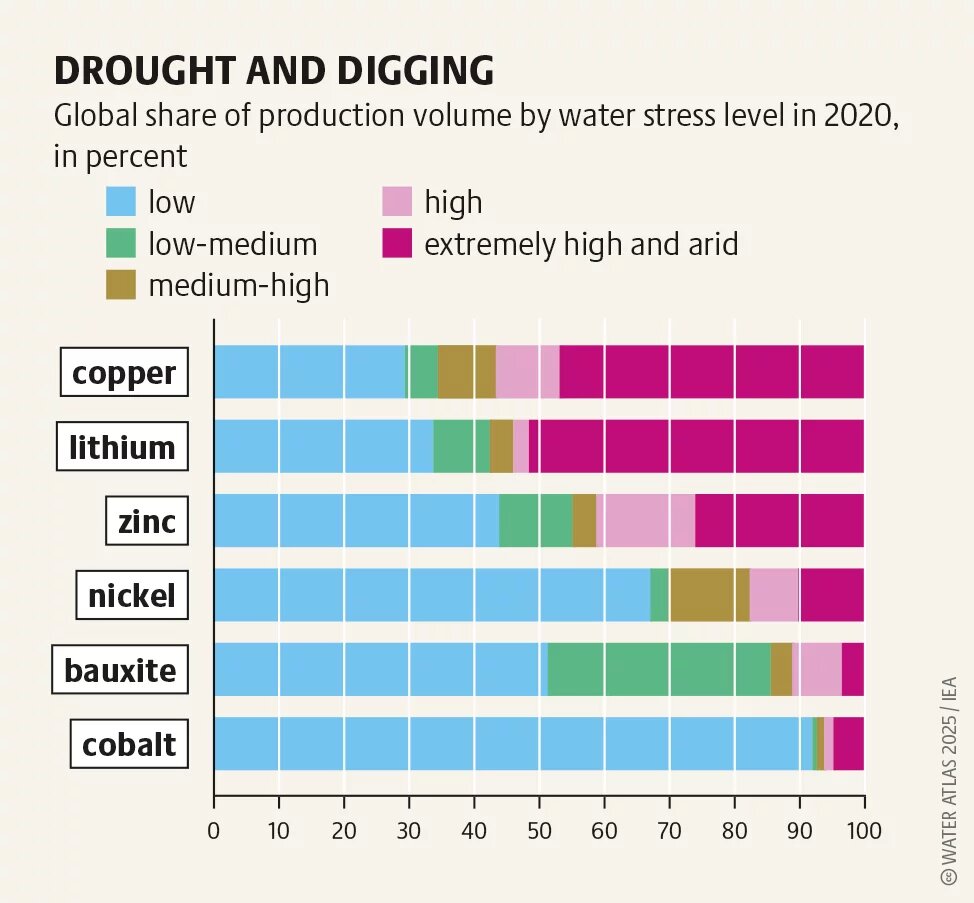

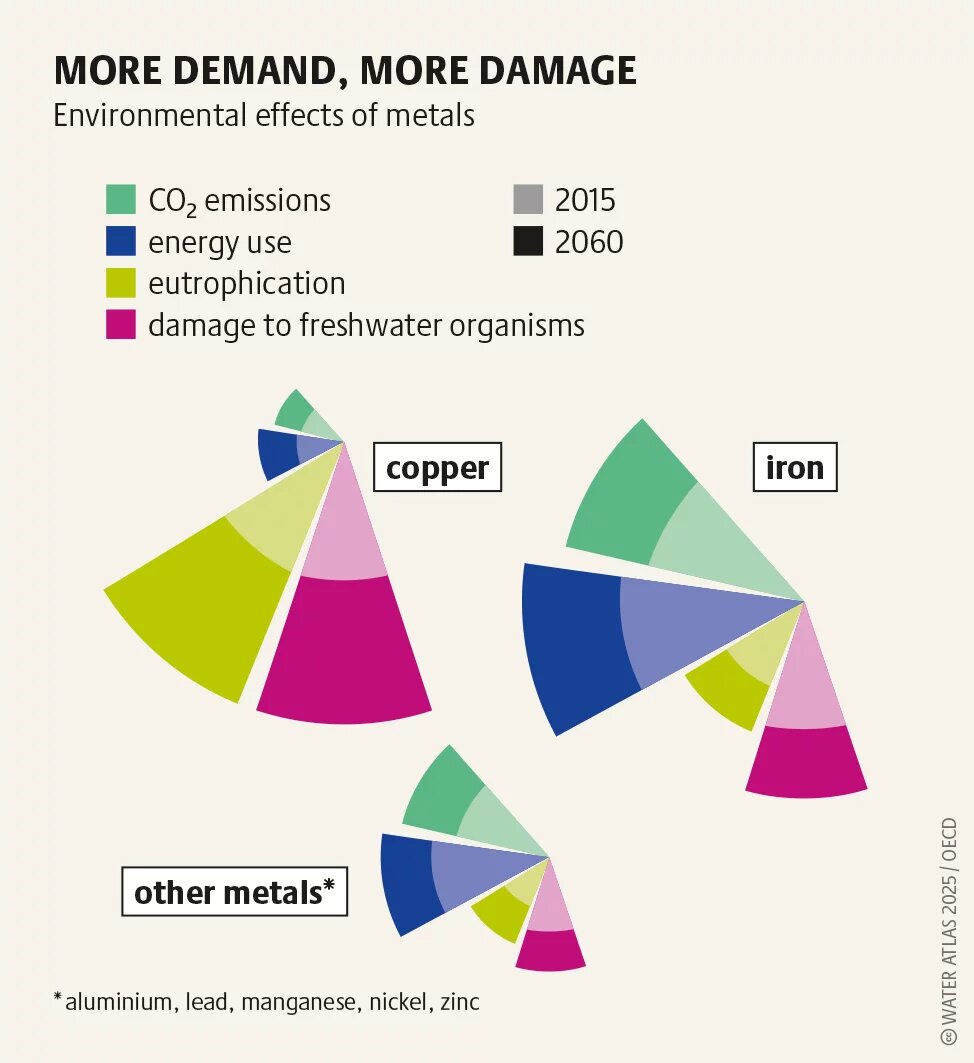

The demand for metals has been steadily on the rise for years. Global demand for rare earths is projected to more than double by 2040, with lithium demand increasing thirteenfold. All that has an impact on the availability and quality of water. Producing one kilogram of the copper that will go into power lines or boilers consumes around 97 litres of water. Thus, the amount of water used for one tonne of copper equals the drinking water requirements of one person in Germany for 177 years. Between 400 and 2,000 litres of water are needed to obtain a kilogram of the lithium needed to make batteries for electric cars.

China and the USA are the largest consumers of minerals and metals, while in Europe, Germany is responsible for the highest consumption. The construction and automotive industries have a particularly high demand as they need large amounts of copper and aluminium.

Over 90 percent of raw materials consumed in Germany are imported, with Chile being a key supplier. That country is the source of almost one-third of the lithium and nearly one-quarter of the copper on the world market.

That has consequences: mines have been encroaching on glaciated areas for years. The glaciers act as reserves of fresh water; their long-term accumulation and melting of ice provide a basic level of water security. Some 70 percent of Chile’s population are currently supplied with water from the country’s glacier-rich mountains. The climate crisis is already taking its toll on the glaciers – and the mining is damaging them further. It blasts them away, dumps waste rock on them, or covers them with dust, which causes the glaciers to melt even faster. Mining also contaminates local water sources, leaving some villages in the Andes reliant on water deliveries. In the Salar de Atacama, one of Chile’s most important mining regions, copper and lithium mining have already used up more than 65 percent of the available water supplies. This disproportionately impacts local communities, as Chile’s water resources are privately owned, and the law prioritises industrial use. In many other countries, too, multinationals dominate the extraction of raw materials. Their profits do not benefit local communities in mining areas, where poverty rates are often especially high.

The Global Environmental Justice Atlas currently documents almost 900 mining-related conflicts worldwide. Around 85 percent of these concern the use and contamination of surface water or groundwater. Displacements are common, and in many cases environmental activists and Indigenous People are killed. In some countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, cobalt and coltan mining relies on forced labour.

The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act of 2024 aims to boost Europe’s mining sector. Doing so will also bring the problems associated with mining more strongly into focus in the European Union (EU). What is certain is that the only way to mitigate the harm caused by mining is through robust political regulation and effective enforcement. Mining should generally be prohibited in areas with springs and in very dry areas with sensitive ecosystems and glaciers.

In terms of water supplies, the population must have the top priority. Companies must prevent human rights abuses and environmental risks throughout their supply chains, and those affected need access to remedy. But in the long term, the environment can be protected from mining only if policies reduce the demand for raw materials as much as possible. The idea of a circular economy offers some guidance on how to do this. The European Union’s Ecodesign Regulation aims to minimise the effects of products on the environment through sustainable design. Because minerals and metals are often used to make solar panels, wind turbines, and electric cars, extending this regulation to cover renewable energy would be a modest but useful step. A shift in the transport and construction sectors is essential to reduce their reliance on raw materials and protect water resources. Basically, this includes a future with fewer cars, more bike lanes, and improved public transportation.