Cargo bikes play a big role in avoiding motorised transport of goods. Many European cities operate successful cargo bike subsidy schemes. Commercial use, private ownership, sharing— all forms of cargo bike use are on the rise.

Thanks to modern cargo bikes and bike trailers, about half of all motorised trips for the transport of goods within European cities could be shifted to bicycles. This objective was already proclaimed by EU transport ministers in their 2015 ‘Declaration on Cycling as a climate friendly transport mode’. Based on a study by the EU funded ‘Cyclelogistics’ project, this potential of shiftable goods transports is divided into 69 percent private and 31 percent commercial trips. A study on the private use of cargo bikes in the US shows that cargo bike owners reduce their car trips by 41 percent after the purchase of a cargo bike.

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, there is an increasing need for invidualised transport that is beneficial for both the environment and human health. Using a cargo bike to transport goods or children fulfills both functions.

While cargo bikes have a long continuous history in postal delivery in many parts of Europe, the its current revival originates in the alternative culture of the 1980s and in kids’ transport. The three-wheeler Christiania Bike from Copenhagen has become a symbol for this revival.

Starting from Denmark and the Netherlands, cargo bikes designed to transport kids have increasingly spread across other European countries since the turn of the millennium. Small innovative start-ups as well as big international logistics companies increasingly test and use cargo bikes as a fast, cost-efficient, zero-emission transport option mainly in dense urban areas. In the logistics sector, this requires infrastructure in delivery areas (‘Micro Hubs’ or ‘City Hubs’) to effectively reload goods or parcels from larger vehicles to cargo bikes.

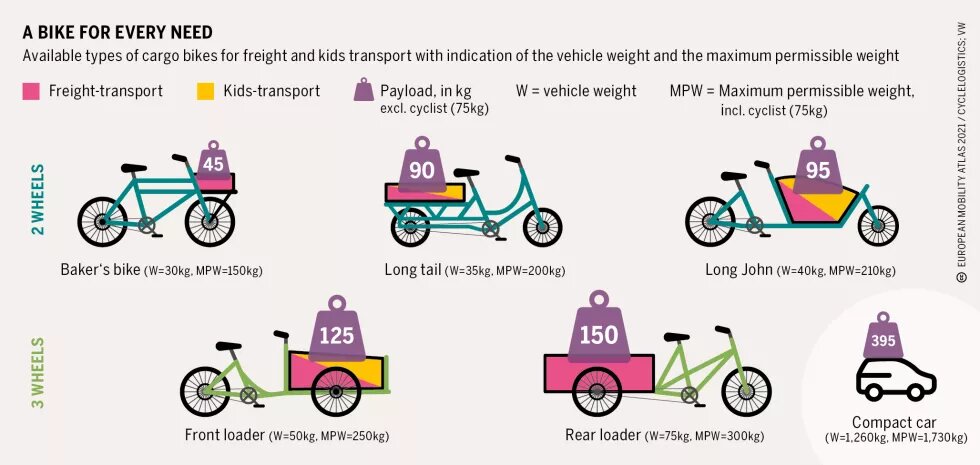

Modern cargo bikes – especially with electric assist – offer transport capacity between 40 over 250 kg for goods and persons. These cargo bikes legally remain bicycles across the European Union as long as their electric assist cuts-off at 25 km/h, has an average power of max. 250 watts and they do not exceed possible limits for dimensions and weights of bicycles in national street codes. There is a broad and increasing variety of mainly two- and three-wheel but also four-wheel cargo bikes for private and commercial use. Their joint characteristics and the best definition of cargo bikes is: they are bicycles that are specifically developed for transporting goods or people and not mainly their rider.

In 2011, the Austrian city of Graz started to subsidise commercial cargo bikes and jointly-used private cargo bikes with up to 1,000 euros. Meanwhile, there are numerous cargo bike subsidy schemes across Europe. Many focus on commercial cargo bikes and are often part of broader e-mobility schemes. In addition, specific subsidy schemes for private cargo bikes recently had overwhelming success in Vienna, Oslo, Hamburg and Cologne. The city of Stuttgart, capital of the German car industry, even pays an extra bonus of 500 euros if families have stayed car-free or reduced the number of cars in their household for a period of three years after their e-cargo bike purchase.

In Germany and Austria, cargo bike-sharing has spread mainly through civil society grassroots movements since 2013. Today, a network of currently more than 70 Commons cargo-bikesharing initiatives exists across Germany and Austria. Commons cargo bikes are rented via a jointly developed booking software and without a fee. The biggest Commons sharing initiative ‘fLotte Berlin’ operates a fleet of 120 cargo bikes in the city.

A survey of 931 Commons cargo-bikesharing users showed that 93 percent of users intend to use a shared cargo bike again while a third (35 percent) of users intend to buy their own cargo bike. There is a continuous demand for shared cargo bikes, while sharing systems also stimulate private sales. The positive environmental effects are evident: about half of the users (46 percent) avoided a car trip by using a shared cargo bike. To foster these environmental benefits, an increasing number of European cities (such as Grenoble, Strasbourg, Hamburg and Stuttgart) are integrating cargo bikes into their conventional bike-sharing fleets. In Switzerland, the commercial cargo bike-sharing system carvelo2go currently runs over 300 e-cargo bikes in more than 70 cities.

In sum, all three forms of cargo bike use – commercial use, private ownership, sharing – are on the rise and have a considerable potential to reduce motorised traffic. However, this potential is not recognised enough. Subsidy programmes, sharing systems and test events for cargo bikes can make an important difference. But exploiting the full potential of cargo bikes also needs more space and better infrastructure (wide bike lanes, secure parking) for bicycles of all shapes and sizes.

The Covid-19 pandemic increases pressure on municipal governments in Europe to give enough space to modes of transport that are good for human health and for the environment: cycling and walking. They reduce the risk of infection, but only if cycle paths exist and are wide enough for cargo bikes. A few European cities implemented pop-up infrastructure for cycling and walking, most prominently Berlin. There, the city government already had a full plan to transform the urban landscape into a cycling city with protected bike lanes: the Berlin Mobility Act. The implementation of this plan might now be accelerated, which will also provide best practices for cycling infrastructure that is ready for cargo bike usage.

Sources for data and graphics: Sophia Becker & Clemens Rudolf, Exploring the Potential of Free Cargo-Bikesharing for Sustainable Mobility, https://bit.ly/3643Pw5; Tom Assmann et al, Planning of Cargo Bike Hubs, https://bit.ly/32hoj3z; Infoportal »Lasten auf die Räder!« des ökologischen Verkehrsclub VCD, https://bit.ly/34CETfA