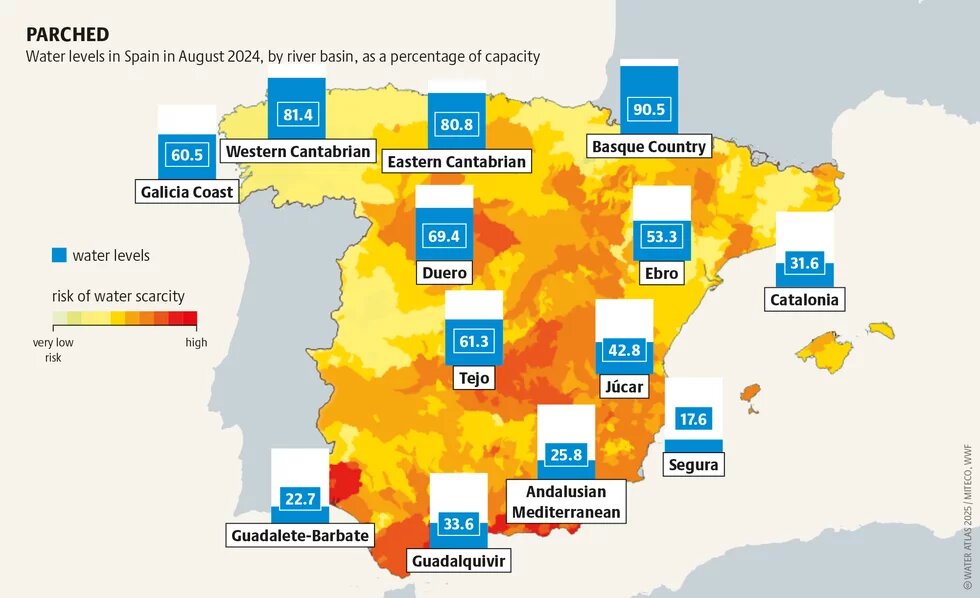

Spain is Europe’s vegetable garden. The country is an example of how export-oriented industrial cultivation methods lead to water shortages and pollution, as well as accelerate the loss of species. To overcome such crises, a sustainable reorganisation of the food system is necessary.

The official figure for Spain’s irrigated area is over 4 million hectares. However, the actual figure is probably a lot higher: it is estimated that roughly another 1 million hectares are irrigated illegally. The high levels of water use for agriculture have drastic and far-reaching consequences for ecosystems. The Doñana National Park in Andalusia is a prime example: this famous UNESCO World Heritage Site with its rare waterbirds, flamingos, and herons was once regarded as one of the most important and diverse wetlands in Europe. But the diversion of water for nearby strawberry plantations and expanding tourist facilities has almost completely dried out this fragile area. In recent years, the park has suffered its biggest decline in species ever. Between 2020 and 2021 alone, the number of birds fell from 470,000 to just 87,500.

In Almeria, also in Andalusia, greenhouses covering an area of over 30,000 hectares are extensively used to grow vegetables, mainly using groundwater. This extraction results in a water deficit of 170 million cubic metres a year. Because the area is very close to the sea, this unsustainable overuse allows seawater to seep into deeper groundwater layers, making the freshwater saline and unsuitable for both drinking and farming. For such reasons, many Spanish provinces have become dependent on external sources of water or expensive desalination plants. The Carboneras desalination plant in Almeria has a production capacity of 42 million cubic metres of water a year, making it the second largest such plant in Europe. It consumes a great deal of energy and emits enormous amounts of greenhouse gases.

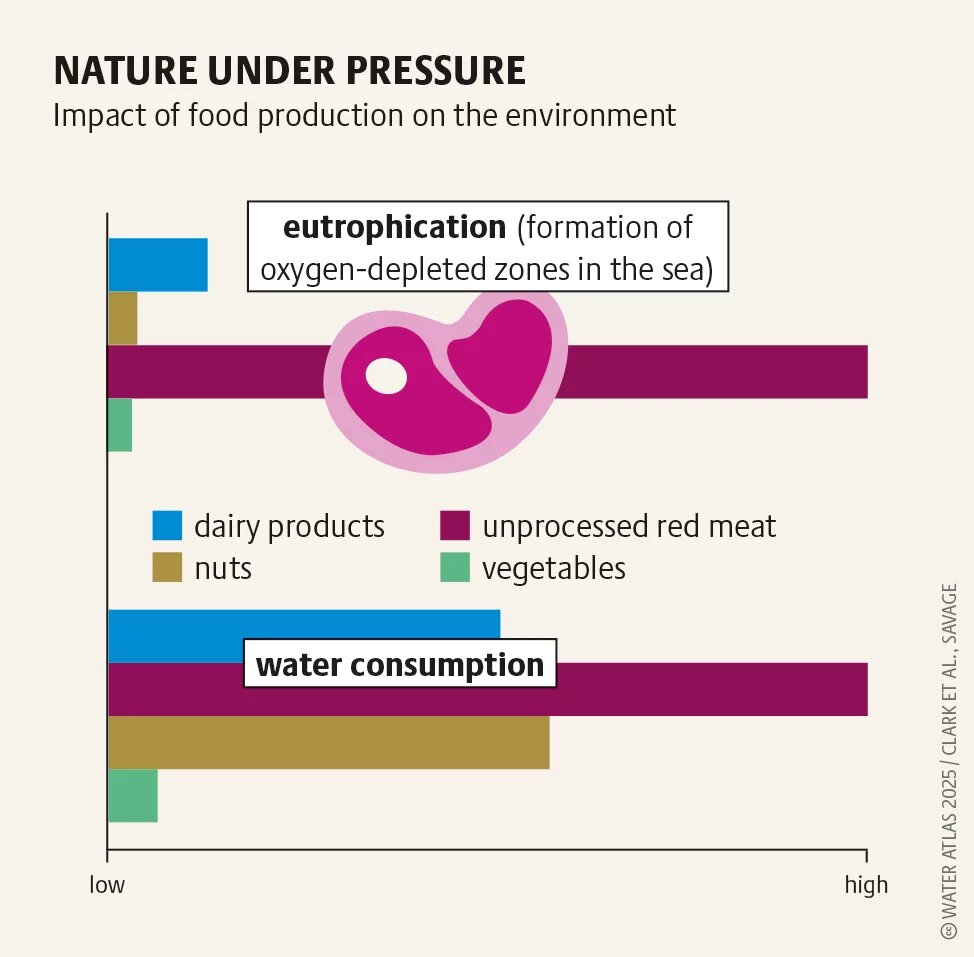

Industrial agriculture not only consumes water but also salinises and pollutes it. In Spain, 11 percent of the surface water and as much as 37 percent of the groundwater have nitrate concentrations above the applicable European environmental quality standards. In 2024, the European Court of Justice ruled against Spain because it had failed to fulfil its obligations to protect water from nitrate pollution from agricultural sources in eight of its autonomous regions.

The best-known case of water pollution is the Mar Menor lagoon in the Murcia region. This is Europe’s biggest saltwater lagoon, and its salt-rich and nutrient-poor water makes it a unique ecosystem. But the Mar Menor has for years suffered from repeated environmental crises, mainly because of large quantities of nutrients entering the water through heavy irrigation and excessive fertilisation on nearby farmland. This has led to a massive decline in native species over several years in a row. In 2016 alone, 80 percent of the seagrass meadows disappeared.

Many water bodies in Spain are also heavily polluted by pesticides. The applicable limits for drinking water were exceeded at 54 percent of the measurement stations for surface water. Analyses show that in three-quarters of the cases, the weedkiller glyphosate and its breakdown product AMPA were responsible for the excessive levels. It is migrant workers who are most likely to come into contact with these poisonous substances in industrial agriculture – and these workers are often paid far less than the minimum wage, while also being subject to precarious working conditions and insufficient health and safety standards. In 2022, some 3,370 people in Almeria’s vegetable-growing region were living in shacks without adequate drinking water, and with no connection to the sewerage system or electricity network.

The agricultural hotspots of southern Spain and the devastating state of their surface and groundwater reserves show clearly how industrial agriculture is nearing a breaking point. Despite all the technical measures to improve efficiency over the last decades, be it drip irrigation or the increased use of biological pest control, the belief that technical advances alone can be a solution ignores the fact that the current crises are rooted in agricultural models aiming at quick profits for the few. Solving water crises will require a major rethink. For example, cooperatives that make affordable agricultural land available to small enterprises must be strengthened. It must be made easier for farmers to move away from a purely export-oriented approach. Shorter marketing channels would guarantee fairer prices for agricultural products. Retailers in importing countries also have a responsibility and must be more closely monitored to ensure they comply with European environmental standards. The changes to our food systems are not of interest only to farmers, but to us all, precisely because they are so closely intertwined with the food we eat, the water we drink, the climate, and rural areas.