The build-up to the UN Food systems Summit 2021 has underlined why systems thinking is essential and action is required now, both concerning the ending of hunger and tackling the web of issues that contribute to sustainability.

There have been demanding tests for the world’s food systems over the last two years, with the pandemic, related economic crises and ever more visible signs of environmental and climate stress. Among numerous effects, food systems in Europe put soils under threat, use a great proportion of land for animal feed production and causes damage for water, biodiversity and humans with the overuse of chemical crop protection and fertiliser. Furthermore, unsustainable consumption patterns and ecological disruptions have been identified as drivers of pandemics. The build-up to the UN Food systems Summit 2021 has underlined why systems thinking is essential and action is required now, both concerning the ending of hunger and tackling the web of issues that contribute to sustainability.

Inequalities in the food system: taking stock

Once the pandemic unfolded, the actions and political choices of the past years magnified the inequalities between urban and rural, poor and rich, and the gender gap. These effects did not come out of nowhere but follow from the unsustainable pillars of ecological, economic and social practices that have accompanied us for decades. The interplay of inequalities and environmental challenges were exacerbated, throwing the world further behind in reaching the UN Sustainable Development Goals, including achieving zero hunger (SDG2). Building a sustainable and fair food system, stretching from primary production to consumption in the home, is one of the greatest challenges of our time.

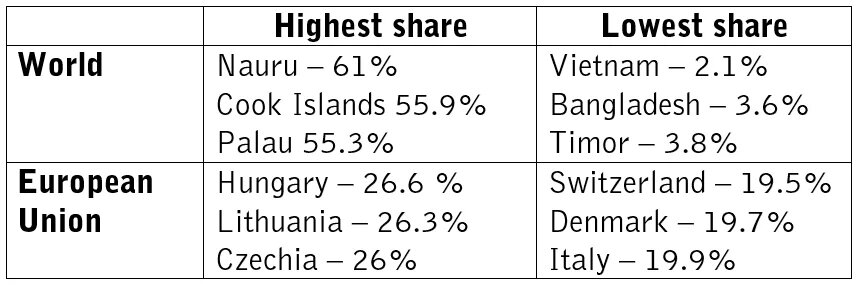

Building towards a sustainable food production system is the goal of SDG 2.4, and there needs to be considerable progress in Europe to move to a system which can be considered as balanced. Particularly certain types of livestock production have been recognized as key driver of pollution and natural resource depletion. To provide the meat for the high levels of consumption, about 67kg per capita availability per year, and for the growing export market, the EU produced 43.6 million tonnes of meat (bovine, pigs, sheep and goat, poultry) in 2019. The sector creates the direct environmental impact of emissions from (especially methane and nitrous oxide), which amount to nearly 70% of the EU’s agricultural GHG emissions. Indirectly, the production of feed crops for animals, estimated to take up 72% of the EU’s agricultural land, drives water pollution, soil erosion and biodiversity loss. Not only is European land use affected by intensive livestock production but the environmental effects are mirrored in the countries which export feed to the EU. The indirect effect of intensive farming system has resulted in a decline of farmland biodiversity of more than 30% since 1990.

Across the world, the cumulative effects of income loss, more volatile and often higher food prices and strained logistics lead to an interruption of access to healthy and nutritious food. In Europe, while it was possible to hold up against the shocks created by the pandemic, the vulnerabilities and embedded social, economic and environmental inequalities in our food system were laid bare. An increase in household food insecurity arose from declining incomes and a consequent decrease in diet quality and diversity. Approximately half of the European population currently suffers from a form of micronutrient deficiency, particularly obesity, and health care costs arising from disease-related malnutrition are estimated at €120 billion annually in the EU. At the same time, the interest in local and sustainable food production spiked among those with the means and time to consume more healthy produce. The pandemic has widened this gap and we can observe how economic, environmental and nutritional crises go hand in hand.

Share of adults that are classified as obese according to the body-mass index greater than 30

Responding to disruptions in the food system

The European food system connects a diverse set of actors, within and outside of the EU. The food system describes the journey of our food from planting to the harvest and the processing stage, over to transport, food marketing, all the way to how we consume food and then its disposal. For a food system to work for all, it needs to be geared towards health, sustainability, inclusivity, efficiency and resilience.

The emphasis on a resilient EU food system emerged in the COVID-crisis, which encompasses the ability to return to a normal state quickly or to bounce back, after a shock. Resilient agriculture and the associated robust production of food should have the capacity to respond to disruptions and crises and to learn from them without causing system breakdowns, including a meaningful response to social and environmental inequalities, and economic volatility. The food system of the future should be one where a shock is a) less likely to occur and b) if it occurs, we know what to do and it then c) has a lower impact, allowing life to continue or adapt quickly.

Preventing future crises by moving to a sustainable food system

Building a resilient food system that works for all requires the right framework of change. Embedded diversity in the food system facilitates the deployment of different options for a robust reaction when a shock occurs, in nature, society, agriculture and the choice of diet. Collaboration and diverse opportunities in the food system create flexibility.

Over the past 20 years, making this change has become more a question of how to govern the interconnected actors. Creating the right food environment for systemic change is a responsibility of governments and retailers. It shifts the responsibility for making all the right decisions for food and nutrition away from the individual and towards the creation of better choice options (income, availability, time). Food habits are shaped by, among others, public policies including procurement and fiscal measures, advertising regulations as well as social systems for equal access to sustainable and nutritious food. Both policy changes and market incentives can incentivise changes and encourage innovative solutions, both social and technological.

Using the political opportunity to refashion the food system

The need for nutritionally and environmentally sound food production has been broadly acknowledged in research circles, long before the pandemic. However, political discussions on reforming the food system frequently result in a dead-end, with far-reaching change being shrugged off as unattainable due to the sheer complexity of the multiple systems involved and the challenge of realigning them in a coherent way. There are many actors to be coordinated and innumerable relationships to be addressed as well as some brave choices to be made.

This hesitation to act is now starting to diminish somewhat within the EU following the high-level commitment to a European Green Deal, including a Farm-to-Fork (F2F) Strategy, as well as the recent experience of the pandemic. The current Slovenian Council presidency has vowed to put resilience and preparedness for pandemics at the centre of their agenda. The proposals in the F2F strategy aims to address both the production and consumption side of the equation, although the main focus is on the former. It also lays the ground for a potentially crucial legal framework for sustainable food systems, with a legislative proposal from the Commission due in 2023. This has the potential to introduce a more cross-cutting approach for a transformation involving a synchronised shift in dietary patterns and food choices alongside changes in production, land use, food processing and marketing pursuing both greater sustainability and improved public health. Still, the main financing instrument, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), as recently agreed for the period post 2022 presents a concerning reduction of environmental and climate ambition initially proposed by the European Commission. It is even more so worrying that the European Court of Auditors, just before a deal was found on the future of the CAP, concluded that the budget attributed to climate (€100 billion) had little impact on GHG mitigation efforts. The fate of the transition towards sustainable farm systems in the EU is now in the hands of the farm ministers and indeed some elements of the deal could still lead to environmental improvements on the ground and improve the resilience of rural areas to climate change, if, and only if, these ministers make the best use of the high degree of flexibility given to them within their CAP strategic plans.

The European food system has an impact well beyond the continent and new generation of policies must take account of this global footprint. They need to actively promote a systematic and fair transition to sustainability on a planetary scale. What we need to see is a U-turn on food system related policy in the EU, with includes the CAP and the F2F. For the CAP, the national agricultural plans must match the long-term strategies (European Green Deal, including F2F) to have a positive climate and environmental impact. Accountability, robust monitoring and transparency plays an essential role to deliver on promises. Now is the time to seize the opportunity to create the food environments that erase economic and social constraints and inequalities that hamper sustainable diets for all.