The UK government has some good ideas for improving the rail network, says Ros Taylor. But cheap fuel, costly buses and a deep-seated aversion to road pricing have driven people away from public transport – and that was before the pandemic.

‘Much of the old demand will return,’ states the Great British Railways Plan confidently. But it is just as well for its authors, transport secretary Grant Shapps and chair of the rail review Keith Williams, that the pandemic has put an end to press conferences, because the obvious rejoinder is, ‘How can you possibly know?’

When Britons were told not to go into the office or make non-essential journeys, they obeyed. The consequences for public transport would have been catastrophic had the government not spent £12bn on bailing out the railways, £1bn on buses and £4bn on Transport for London (TfL), which manages the Underground, buses, trams and some of the capital’s trains.

As England emerges from its third lockdown, it is obvious that office workers are not rushing back to the city centres. ‘Hybrid working’, where staff come in a couple of days a week, is proving attractive. Some employees are not returning to the office at all. At the university where I work, students have (rightly) taken priority: I have not visited the campus for 15 months.

Yet people have not stopped travelling. Motor traffic, which fell 63% in April 2020 – with an overall fall of 21% last year – has come roaring back. Data from London’s road traffic cameras confirms what any Londoner can see, smell and hear: in May, car traffic was at 118% of the levels recorded before the first lockdown. It is true that cycling is up (123%), but from a very low base. Pedal bikes travelled just five billion miles last year, as opposed to 210 billion by cars and taxis. As I look out of my kitchen window, dozens of cars – directed here by satnav systems - wait to turn onto the gridlocked main road. The queue has been building for two hours. Until this year, the road was invariably quiet.

Train companies and the Underground are doing their best to allay fears about the virus. Masks are compulsory and the majority of passengers wear them. The Tube points out that its draughty trains and frequent stops result in a change of air every three minutes. Yet either people are still afraid of catching COVID on public transport, or they have got into the habit of using a car during the pandemic and are reluctant to abandon it.

So the question of how to reorganise and promote public transport is urgent. Although more people travel by train than they did before the railways were privatised in 1994, splitting up responsibility for tracks, stations and trains created enormous inefficiencies. The government’s answer has been to not renationalise the railways, but to simplify them. ‘In short, we need somebody in charge,’ declares the Williams-Shapps review. Tickets, which are infamously complex, must be easier to buy, and more trains should run on time; one in three are currently late.

Railways are seen as a way of affirming Boris Johnson’s commitment to the north of England. After the expense of Crossrail, an east-west London route that was supposed to open in 2018 but is still not functional, the government wants to reward the North. The High Speed 2 route from London to Birmingham, Manchester and Leeds is going ahead and should open in 2029, and money has been spent on upgrading tracks and trains in the North.

In some ways buses have suffered similar problems to the railways. In London, fares are relatively cheap and planning a journey is simple. Elsewhere, however, they are expensive, fragmented and tickets are difficult to buy. Unfortunately, Johnson’s introduction of ‘Bus Back Better’ – ‘our vision for the future of buses’ – does not inspire confidence. ‘I love buses,’ declares the prime minister. ‘As mayor of London, I was proud to evict from the capital that mobile roadblock, the bendy bus, and to replace it with a thousand sleek, green, street-gracing New Routemasters.’ While the New Routemaster is certainly distinctive, its design flaws are legion, and bus ridership started to fall when Johnson was still London mayor. Outside the capital, it is falling even faster.

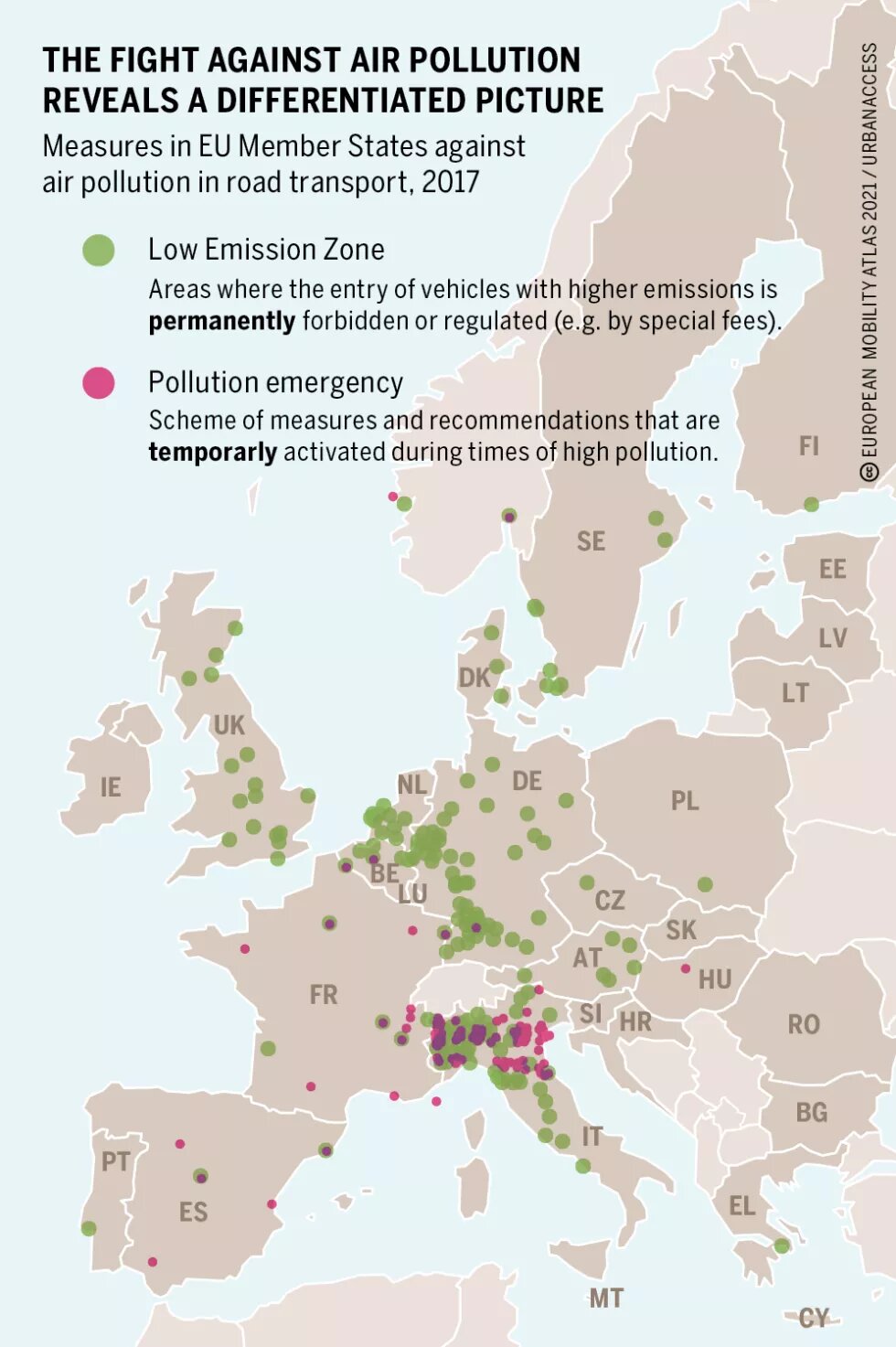

‘Bus Back Better’ aims to enable local authorities to set up ‘enhanced partnerships’ in which authorities have more of a say over ticketing, pricing, timetables and routes. Some of these may eventually become franchises, although the government does not intend to give local authorities as much power over services as TfL has. In short, the document is mostly aspirational. But, as it points out: ‘In congested areas, substantial modal shift away from the car will soon be needed if clean air targets and the government’s broader climate goals are to be met. The only mode capable of sufficient expansion in the time available is the bus.’ Indeed.

The problem is that driving is so cheap (although the real costs are hidden in many countries by cross-subsidies/tax breaks). The cost of driving a car has risen 9% since 2011, while bus fares are up an extraordinary 75% and train fares 37%. Certainly, buses need to be cheaper and more frequent. But unless the cost of motoring rises, people will stick to their cars. As the Harvard economist Edward Glaeser puts it:

‘There is no substitute for doing something that functionally taxes carbon. You can’t just subsidise alternative uses of transportation and hope that it will work out. You need to do something that actually limits people’s incentive to fly or drive, and that requires a tool like congestion pricing.’

What are the chances of Britain adopting widespread road pricing? At the moment, they look slim. Raising fuel duty has been considered politically toxic since 2009. Road pricing was mooted but fell out of favour at the same time – except in London, where gridlocked traffic has made the Congestion Charge acceptable. The current mayor will extend the Ultra Low Emissions Zone into suburban London in October, but this is an attempt to improve air quality rather than tackle congestion. And while the extent of the exodus from cities during the pandemic is not yet clear, rising demand for homes in rural areas can only drive car ownership up further.

It would be foolish to bet on a renaissance in public transport in the UK. A few developments, however, do offer some hope for change. One is the growth of carpooling schemes such as Zipcar that target the occasional motorist: when each journey must be booked and paid for, people are more likely to walk, cycle or take the bus for short trips. Another is the increasing sophistication of transport apps and the possibility that they might one day support buses on demand as well as Ubers. ‘Bus Back Better’ predicts that they could become particularly useful in the countryside and for women who are nervous about travelling at night, because they would offer a door-to-door service. Electric bike hire is gradually becoming more common in some cities and, again, is enabled by apps.

Perhaps in time it will be possible to apply the principle of surge pricing to car use: when pollution is high or the roads congested, the cost of driving will become prohibitively high. If predictions about electric car use come true, air quality may cease to be a problem. But right now, the public are choosing the cheap, convenient and COVID-free option: their own cars.