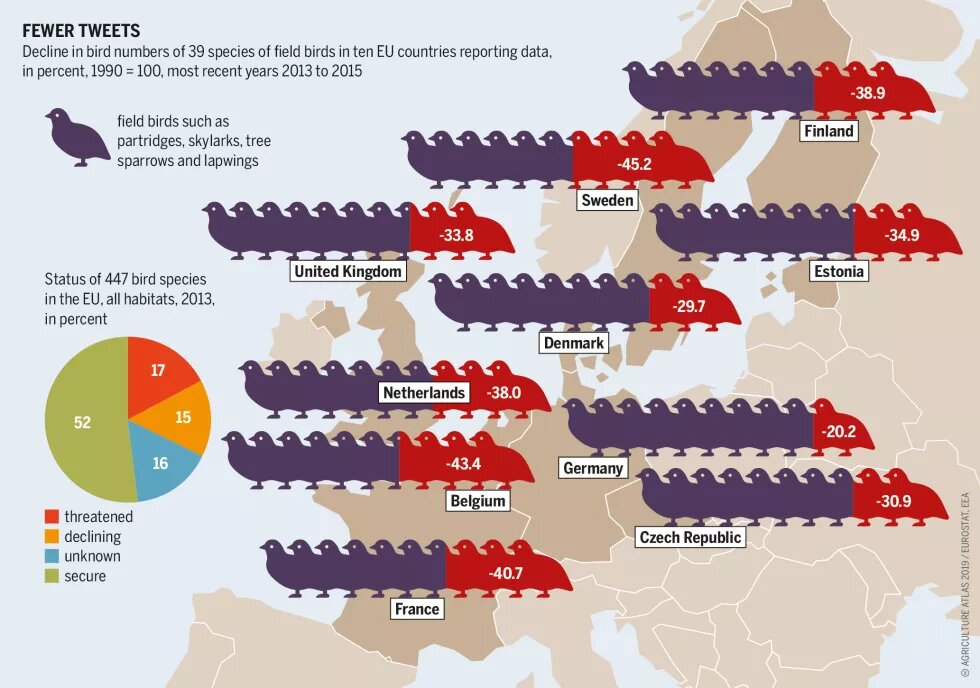

Wildlife is under severe pressure in the EU, with 60 percent of species and 77 percent of habitats classified as having “unfavourable” status. The number of farmland birds has declined by 57 percent since 1980, and there are almost 35 percent fewer grassland butterflies than in 1990. Even once-common farmland birds are disappearing. For example the European Turtle Dove is facing extinction: its numbers declined by 77 percent in Europe between 1980 and 2012.

In Germany, insect numbers have fallen by over 75 percent since 1990. In France, a third of farmland birds species have vanished in the last 15 years. “Generalist” species that can live in different types of habitat have done worse in farmland than in urban areas. In central and eastern Europe, the numbers of farmland birds fell by 41 percent from 1982 to 2015, compared to a 6 percent drop in forest bird populations.

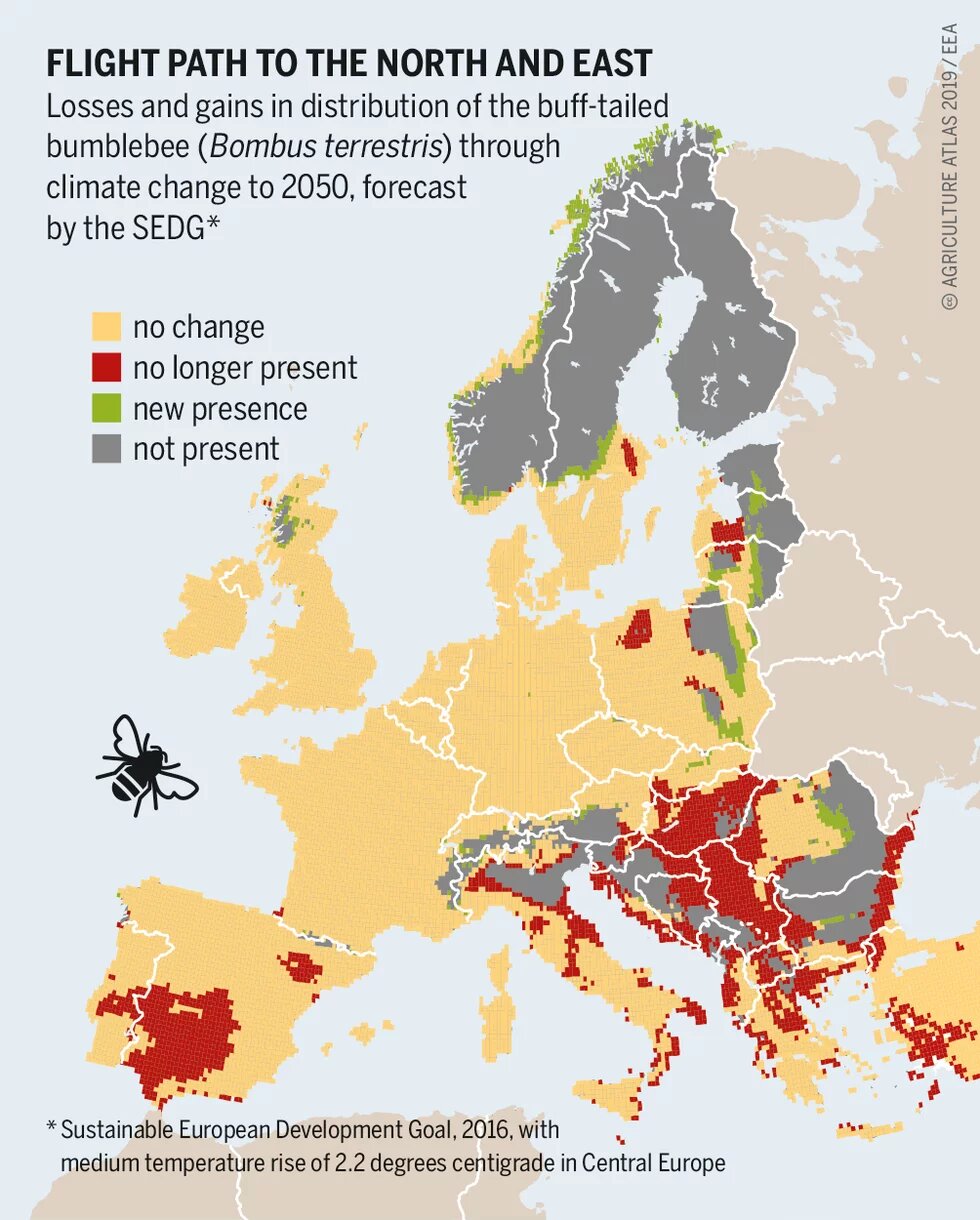

According to the European Environmental Agency, agriculture is the biggest threat to biodiversity. That is mainly due to intensive farming, which has an impact independent of other factors such as climate change.

Practices that maximize short-term yields mean less food for wildlife. Monocultures, a loss of natural vegetation, along with pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers, reduce the food supply for species that eat weeds, seeds and insects. In the UK, bat populations bounced back quickly when farms converted to organic production because insects became more abundant.

Using farmland intensively means less breeding habitat for wildlife. It involves removing landscape features such as small wetlands, and ploughing up or intensifying the use of grasslands. In France, there was a 95 percent decline in the numbers of Little Bustard between 1978 and 2008 because grasslands were converted to cropping.

Intensive farming also has an indirect impact on wildlife. Agriculture is the biggest threat to Europe’s wetlands. It diverts or pumps water for irrigation, and pollutes it with fertilizers and pesticides. Excess nitrogen in soils from fertilizers and manure reduces plant diversity in fields, which in turn cuts the number of species they can support. Nitrogen runoff causes algal blooms that kill aquatic species.

The EU spends 39 percent of its total budget under the heading “Sustainable growth: natural resources”. This covers the Common Agricultural Policy, fisheries and marine funds, and an environment fund named LIFE. The CAP receives 97 percent of the funding within this budget; LIFE gets just 0.8 percent.

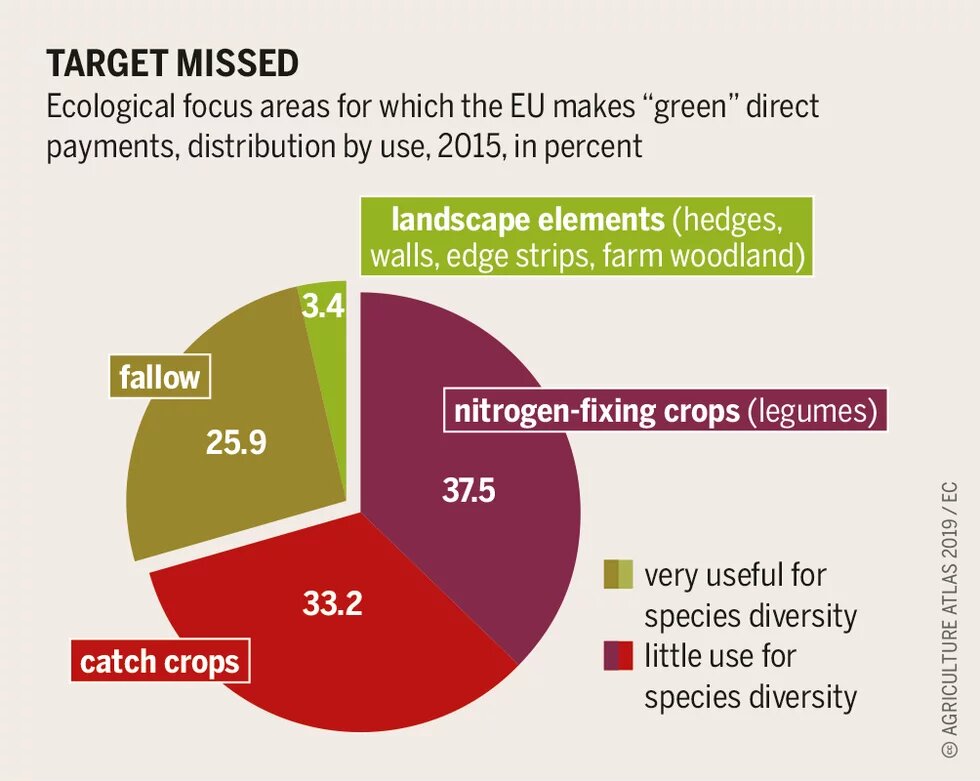

The EU is obliged by law to fund its nature protection laws, and EU leaders have promised to do so. But the current budget has no guaranteed spending on biodiversity. Nor does the next budget. Rather than designating a stand-alone pot of money, leaders chose to integrate nature funding into the Common Agricultural Policy. But this fails to deliver significant support for biodiversity conservation, while subsidies instead go towards further intensification.

Reforms to the Common Agricultural Policy in the 1990s and early 2000s tried to break the link between payments and production levels that led to wine lakes and butter mountains. They introduced agri-environmental schemes and basic environmental conditions for payments. Despite these, the CAP remains heavily biased in favour of intensive farming. That can be seen in the Czech Republic: a 2018 study shows that farming intensified and farmland bird populations declined steeply after the country joined the EU.

The CAP measures that get the most money are the most “perverse” – a term used by the Convention on Biological Diversity to describe subsidies that harm the environment. Nearly three-quarters of the funding (around 293 billion euros for 2014–2020) goes to direct payments that favour the most intensive and damaging forms of farming: cereal and livestock production. These payments are made for the area farmed, rather than being linked to practices or meaningful rules on sustainability. Another 15 percent of the funds go to production support (e.g. paid per animal or unit yield of grain); this goes mainly to the meat and dairy sectors, contributing to overproduction. The vast majority of “investment aid” (one-off grants for farm investments) also supports intensification, for example to purchase heavy machinery, build processing plants or set up intensive livestock pens.

Of course there are many good local examples of schemes that work and farmers who support biodiversity. But their impact is undermined by a lack of funding and the considerably larger spending on perverse subsidies, or they are “out-competed” by less demanding or bogus schemes. For example, Cyprus has a generous (800 euros per hectare) scheme for the “environmentally friendly” management of banana plantations, which even allows herbicide use. This is justified by claims that it avoids construction development and is somehow good for wildlife. To halt and reverse biodiversity loss due to intensification, adequate funding is needed for specific biodiversity measures on farms, along with the right rules and incentives to spur a transition to less intensive farming.