Since the 1980s, the Common Agricultural Policy has frequently been the subject of criticism for subsidizing the export of farm products to other parts of the world. This use of taxpayers’ money led to a decline in world market prices and forced farmers in the developing world out of their local markets. Area payments – subsidies per hectare farmed – have been the Common Agricultural Policy’s principal instrument since the 1990s. Export subsidies shrank, and were banned in 2015 worldwide after a ruling by the World Trade Organization.

Disagreement exists as to whether the area payments have a negative effect on developing countries. The payments are made regardless of what is grown or how it is grown. A large majority of agricultural economists assume that the payments barely affect production and have little international impact. But economic modelling shows that both production and exports would change significantly if no area payments were made. A 2012 study by the Norwegian Agricultural Economics Research Institute concluded that net exports of wheat from the EU would decline by 20 percent, pork by 15 percent, and poultry by 75 percent because eliminating area payments would push up cereal prices, increasing the cost of feed. According to the authors of this study, these effects are minor. However, NGOs have a different opinion. They say that the effects would be significant if the EU, a major exporter, were to reduce its commodity volumes to such an extent.

Current trade figures show that the EU now has a trade surplus in agriculture: it earns more from commodity exports than it spends on equivalent imports. Things were the other way round in the era of export subsidies. In particular, the export volumes for wheat, pork and milk have risen, with exports now taking up a bigger share of the EU’s total output.

Africa is an important market for many commodities. In 2017, North Africa, with its limited potential to grow its own food, took 35 percent of the EU’s wheat exports. Sub-Saharan Africa took more than a quarter – and two thirds of the EU’s flour exports. Admittedly, wheat can be grown in only a few places south of the Sahara, but imports compete with locally adapted crops such as millet, cassava and yams. Around 43 percent of the EU’s poultry meat exports went to sub-Saharan Africa in 2017, mainly to West Africa. Abolishing the area payments would, according to the model, reduce exports and raise meat prices in the importing countries. That would stimulate investment in local production and improve the current low productivity in this industry.

Most scientists and NGOs agree that the EU’s export successes depend on more than subsidies alone. The EU has long pursued the explicit goal of boosting its farm productivity. Because sales in the EU have stagnated, production can only be increased by boosting exports. The construction of ever-bigger livestock houses, plus lax environmental and animal-welfare controls, have led to higher production and lower prices for producers.

The milk market shows how things can go wrong. The EU milk policy was liberalized in 2015, and the production limits introduced in the 1980s were abolished. That allowed European dairies to export more. But the higher exports led to a collapse in world market prices. The big European dairies simply passed on the lower prices to the farmers, forcing many out of business, or necessitating state support in the form of emergency loans.

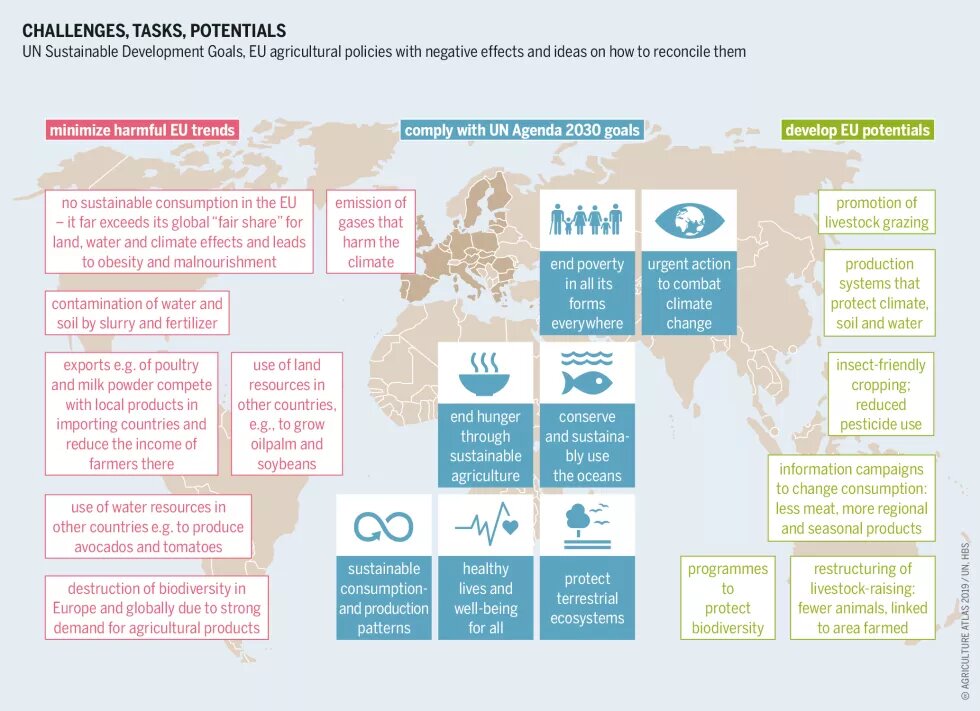

By getting rid of export subsidies, the EU has eliminated an element of its agricultural policy that was particularly damaging to developing countries. But that does not make the Common Agricultural Policy blameless. Agricultural imports into Europe are of particular concern. Most of these still consist of traditional raw commodities and former colonial products: palm oil, soybeans, cacao, coffee, bananas and cotton. Conflicts over the use and distribution of productive land, along with deforestation, water use and pesticide applications have negative effects on food, health, human rights and global sustainability. Soybeans, used in the EU for animal feed, are an example. The Common Agricultural Policy promotes the production of pork and chicken, driving the demand for soya, which is grown on huge estates in Latin America on land once covered by forest and savanna.

The task is enormous, but the goal is clear: the EU must fundamentally restructure its agricultural and food systems, on which it currently spends 41 billion euros for direct payments. It must make them both ecological and globally equitable. Only then will it make a tangible contribution to the global goals of sustainable development and the UN Agenda 2030.