Questions of environmental and climate policy remain relevant even during a pandemic, as the protests and debates about the stimulus package to fight the crisis show. The German states have taken on a deciding roll regarding questions of implementation – which started already during the negotiations for the climate package. The Greens contributed the most to the climate package's increased substance.

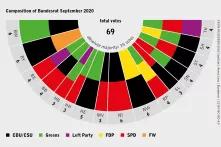

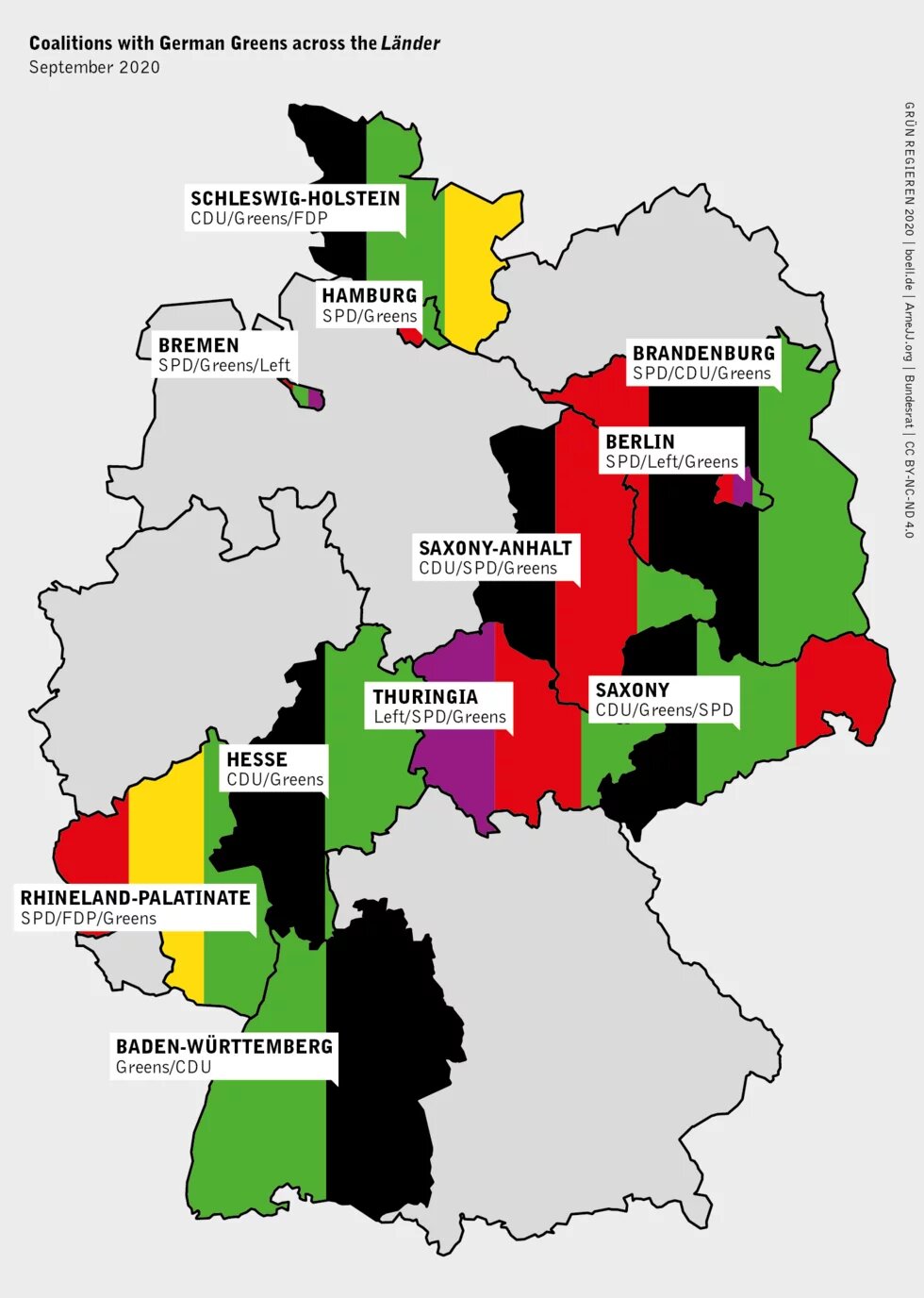

In Germany, the climate crisis and the state of the environment remain highly urgent matters even in times of pandemics, as the protests and debates around the economic stimulus packages to combat the effects of the crisis show. In Germany’s political system, the 16 Länder in particular play a decisive role when it comes to implementation. As of August 2020, Alliance 90/The Greens, Germany’s Green party, governs in 11 out of the 16 Länder. This presence has allowed the Greens to shape and improve the most recent climate package of the Grand Coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD. Media overwhelmingly agreed that the involvement of the Greens clearly improved the federal government’s original draft.

The Greens have exerted pressure on the national coalition through their Länder governments in the Bundesrat, the upper house of the German parliament. In particular, they brought about a higher carbon price (Tagesschau). Because they threatened to block the climate package, the conservative CDU/CSU gave in on the issue (Der Spiegel). The Greens flexed their muscles in the Mediation Committee, whereas the coalition partners on the national level would not have succeeded in getting the Greens on their side in a single Land (FAZ). Armin Laschet, CDU state premier of North Rhine-Westphalia, subsequently declared that the compromise was "naturally ... a result of Green influence".

The starting position for the Greens was not necessarily favorable, as the national coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD had structured the climate package so that important measures - including the carbon price - were included in laws that did not require the Bundesrat’s approval. In the Mediation Committee, which negotiated the final compromise on December 18, 2019, the Greens only have two of the 32 members. So why were the Greens able to push through improvements despite an unfavorable starting position?

Weak draft of the Grand Coalition

After tough initial deliberations between CDU/CSU and SPD, the federal government adopted its draft of the climate package on 20 September 2019. Environmental groups and climate scientists were sharply critical. Germany’s section of Fridays for Future, the movement whose protests brought around 1.4 million people to protest on the same day in Germany alone, spoke of a slap in the face for future generations. The pressure that the movement had effectively built up over months was expressed in surveys. In the ZDF Politbarometer published the following week, 53 percent of all respondents criticized the climate package as not far-reaching enough – including 39 percent of CDU/CSU supporters. 59 percent of those surveyed stressed that climate change was currently the most important problem in Germany. The Greens were not only held to have the greatest competence of all parties in climate protection, but most of those surveyed (55 percent) said that the Greens represented their stand on the issue.

In short, the coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD presented a weak draft that did not even convince their own supporters. In the course of the next few weeks, several state premiers from the coalition's own ranks also demanded changes. Lower Saxony's state premier Stephan Weil (SPD) criticized the carbon price for being too low. He said that the symbolism did not fit: one ton of CO2 only cost as much as three to four beers. North Rhine-Westphalian premier Armin Laschet (CDU) and Bavarian premier Markus Söder (CSU) also called for changes to the package.

Green unity: increasing the carbon price

The Greens worked early on to find a common position between the federal leadership (both the board of the national party as well as the parliamentary group in the Bundestag) and the Greens governing in the Länder. As the climate package concerns their core issue, they wanted to demonstrate unity under all circumstances. Differences within their own ranks were to be avoided for two reasons: contradictions, especially in the Green core issue, have a negative effect on public image; and internal disputes weaken the Greens’ position in federal negotiations, as shown in the 2014 reform of Germany’s Renewable Energy Law EEG. At the time, the Greens pursued a dual strategy, in which they tried to improve the reform via the Länder, but opposed it on the national level. This tactic proved to be a difficult balancing act.

Therefore, the Greens did not want to retreat to a veto position in the Bundesrat on the climate package. They wanted to demonstrate their ability to govern and also to substantially improve the package. The aim was to appear as a strong political force with their own concepts. To underscore this, the Greens published an Emergency Climate Program on 28 June 2019 presented by three top Green politicians: Federal Party Chairwoman Annalena Baerbock, the Chairman of the Bundestag parliamentary group, Anton Hofreiter, and Baden-Württemberg's Minister President Winfried Kretschmann. In the Program, the Greens proposed a rapid coal phase-out, a carbon price of 40 euros per ton, and a climate protection law.

The carbon price would play the most important role in the negotiations, as the Greens considered it not only to be an effective measure to reduce emissions but also as a high symbolic value and easy to communicate. With relative ease, the Greens at the federal and state level were able to agree on a common position here - unlike, for example, on financial incentives for commuters and a series of smaller tax rules within the climate package.

For drafting the Emergency Climate Program, the Greens used their G-coordination, an informal structure that the party has built up over the last ten years. Its purpose is to deal with the differing interests between the state and federal Greens, to moderate conflicts and to identify common priorities. The Emergency Climate Program was not adopted in a formal party committee, but published as an authors' paper of the top federal and state Greens. In addition to Winfried Kretschmann, all the Green deputy state premiers from the Länder signed the paper, making it a first signal that the Greens wanted to achieve improvements through the Bundesrat.

In September 2019, the Greens in the Bundestag confirmed the introductory price of 40 euros per ton of CO2. A month later, the Greens’ convention (Federal Delegates Conference) called for a carbon price of initially 40 euros, which would rise to 60 euros in 2021. In particular, the increase in 2021 allowed the Greens governing in the Länder to credibly tell their respective coalitions that they could not agree to a climate package with a low carbon price. Thus, the Greens demonstrated unity at an early stage and built up the threat to veto the climate package (or parts of it), if necessary. This threat was credible because public opinion was on the Greens’ side. The public would not blame them if they vetoed the package. Failure of the negotiations was therefore a real option. The federal government was under pressure.

A very Grand Coalition reaches a compromise

The Bundestag passed the initial draft of the climate package on 15 November 2019. The governing parties of CDU/CSU and SPD supported it, the Greens voted against it. Two weeks later, the Bundesrat dealt with the package. For tactical reasons, the federal government separated the draft into two parts: one part considered subject to objections(Einspruchsgesetz); the other, subject only to consent (Zustimmungsgesetz). The Bundesrat has less influence on objection bills than on consent bills. To reject a consent bill, a majority in the Bundesrat is needed. Consent bills, however, can only come into being if the Bundesrat and Bundestag are in agreement. Should the Bundesrat reject a consent bill, the bill in question returns to the Bundestag, which must then address the Bundesrat’s complaints.

In the case of the climate package, the objection bills included the Act on the Introduction of Emissions Trading in Transport and Housing, the Climate Protection Act (which sets binding annual CO2 targets for all sectors), and the Act on the Increase of the Air Ticket Levy. Raising an objection would have required a majority of 35 votes in the Bundesrat, which was out of reach. So the Bundesrat approved the first part of the Federal Government's draft.

The second part of the package included those laws requiring consent from the Bundesrat. Here the Greens, governing in 11 state governments, were in a strong veto position. Without their state governments voting for it, this part of the climate package would have failed. The consent bills of the climate package included an increase in the commuter allowance, a reduction in the VAT on train tickets, and tax incentives for building renovations. Several state premiers across party lines complained the Länder would suffer unilaterally from tax shortfalls under the federal government’s plan. The original draft threatened tax losses of around 2.5 billion euros in the coming years for the Länder, while the federal government was expecting an increasing revenue from the carbon price increase. Naturally, the Bundesrat unanimously called the Mediation Committee, which resolves such disputes between the two chambers of parliament.

The Mediation Committee consists of 16 members for the Bundesrat and 16 for the Bundestag. The Greens have had only two seats at the table: state premier Winfried Kretschmann for the government of Baden-Württemberg and Anton Hofreiter for the parliamentary group in the Bundestag. The Mediation Committee set up a working group with representatives from SPD, CDU, CSU and Alliance 90/The Greens to negotiate a compromise.

The resolution reached expresses the desire for a "fundamental revision" of the bills and served as the basis for the Greens to later to include a higher carbon price in the discussions (the Emissions Trading Act having already been approved). In the political debate, the Greens succeeded in combining their demand for a higher carbon price with concessions on the commuter allowance, which was a matter of particular concern to the CSU.

The working group agreed to redistribute the financial burden of the package in favor of the Länder. In addition, it proposed to increase the commuter allowance for longer distances and to significantly raise the carbon price for buildings and transport in a new legislative procedure. Instead of the 10 euros per ton in the original bill approved by the Bundestag, the carbon price would now be 25 euros from January 2021, then gradually increase to 55 euros in 2025 and up to 65 euros in 2026. On 18 December 2019, the Mediation Committee agreed on these changes to the climate package. The Bundestag and Bundesrat adopted them in the same week, this time with support of the Green Party.

In the aftermath, the Greens have made a balanced assessment of the negotiated compromise: the package was improved, but the compromise is only an intermediate step insufficient with regard to the challenge of the climate crisis.

Conclusion

Despite an unfavorable starting position, the German Greens have improved the climate package. An important condition for this strategy was the party's united stand for a higher carbon price. The Greens have learned from previous experience and made considerable efforts to coordinate internally at an early stage in order to achieve a joint position at the state and federal level. They have demonstrated that they are a federal climate force. This success was possible partly because the Fridays for Future movement had made it clear for months that the vast majority of the population demands more ambitious climate action. The tailwind of public opinion and the coalition's weak initial draft enabled the Greens to credibly build up the threat to block at least parts of the climate package.

Conversely, the example reveals that this Green negotiating power cannot be randomly called upon or transferred across the board to other legislative procedures. For example, the interests of Greens in Länder governments differ more when it comes to the coal phase-out, for instance: Länder without much coal-fired power generation are pushing for a more rapid shutdown of coal-fired power plants than those in which comparatively modern coal-fired power plants are in operation. Likewise, governments with opencast lignite mining are pushing for more generous structural aid than those Länder where no coal is mined.

Ultimately, the example shows that the federal government is master of the procedure. It has the right of proposal. Currently only in opposition at the federal level, the Greens can at best achieve improvements through the Bundesrat, but they are only in a reactive role. Federal elections are up in September 2021. Entering a coalition in the Bundestag would offer greater scope for the Greens to raise ambitions of Germany’s climate policy.

This text is an edited version of the German text Grüne Gestaltungskraft aus den Ländern, which was published by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung here. It was first published by our Washington D.C. office.