The Covid-19 pandemic affects different groups of people differently. It is, however, possible to argue that asylum seekers, migrants and refugees scattered across the globe are among the most vulnerable groups to the outbreak. Yet, what are the key challenges facing migrants and refugees in Turkey, particularly challenges in accessing healthcare services during the pandemic?

According to the Turkish Ministry of Interior’s official data, as of April 17th, 2020, the number of Syrians under temporary protection in Turkey was 3,583,584. Yet, only 63,518 of this number were housed in camps. In other words, millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey are struggling to survive in urban areas. Along with the Syrian refugee population under temporary protection, Turkey is also a hub for irregular migration, hosting an unknown number of undocumented migrants. Turkey offers two separate healthcare tracks for those under temporary protection and others. While persons under temporary protection are entitled to benefit from free healthcare services at primary care stations and hospitals, irregular migrants aren’t afforded this opportunity. However, following the adoption of a decision in April 2020, this situation has improved, at least for the time being, to a certain extent.

As per a April 13th, 2020, Presidential Decree issued as part of the measures against the outbreak, every individual who approaches a hospital with a suspected case of Covid-19, regardless of their health coverage under the social security system, shall be granted free of charge access to personal protective equipment, diagnostic testing and medical treatment. Dr. Deniz Mardin, a public health specialist, believes this decision might be interpreted as an additional measure taken in an effort to tackle the outbreak. Personal protective equipment, i.e. face masks, is on the other hand one of the most controversial topics amid the Covid-19 related agenda in the country. On April 3rd, 2020, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced facemasks would be made mandatory in public spaces, such as markets and supermarkets, and authorities started to distribute free face masks as of April 5th, 2020. On April 6th, 2020, however, the government introduced a ban on the sale of face masks. Although, thanks to the said-decree, persons lacking social security coverage were also introduced to this scheme and migrants still experience challenges in accessing face masks. For instance, just like Turkish citizens, they also couldn’t benefit from free face mask distributions at pharmacies due to various obstacles regarding access. As problems have grown more complex, the government later announced the ban on the sale of face masks would be lifted as of May 4th, 2020.

Returning to the subject of healthcare services provided to migrants in Turkey, there are a total of 180 Migrant Health Centers (MHC) across 29 provinces in the country. Currently, professionals deployed at these centers carry out body temperature screenings on people suspected of having Covid-19, and where necessary, refer these cases to hospitals. As everybody else does, irregular migrants approaching healthcare facilities with a suspected Covid-19 symptoms should also be registered. However, how do authorities register an undocumented person or a person who is under temporary protection and yet currently residing in another city? The answer is these irregular migrants are recorded as “stateless persons” under the Public Health Management System. While this possibility to benefit from healthcare services is a welcome improvement, there are, however, reported difficulties in patient monitoring. A major challenge in this regard is the ongoing risk of possible notification to law enforcement authorities of irregular migrants and refugees registered in other provinces. The risk of deportation can therefore make migrants and refugees more reluctant to approach public hospitals. Civil society organizations and professionals working in the field of migration have repeatedly raised the urgent need for measures that would help eliminate this risk.

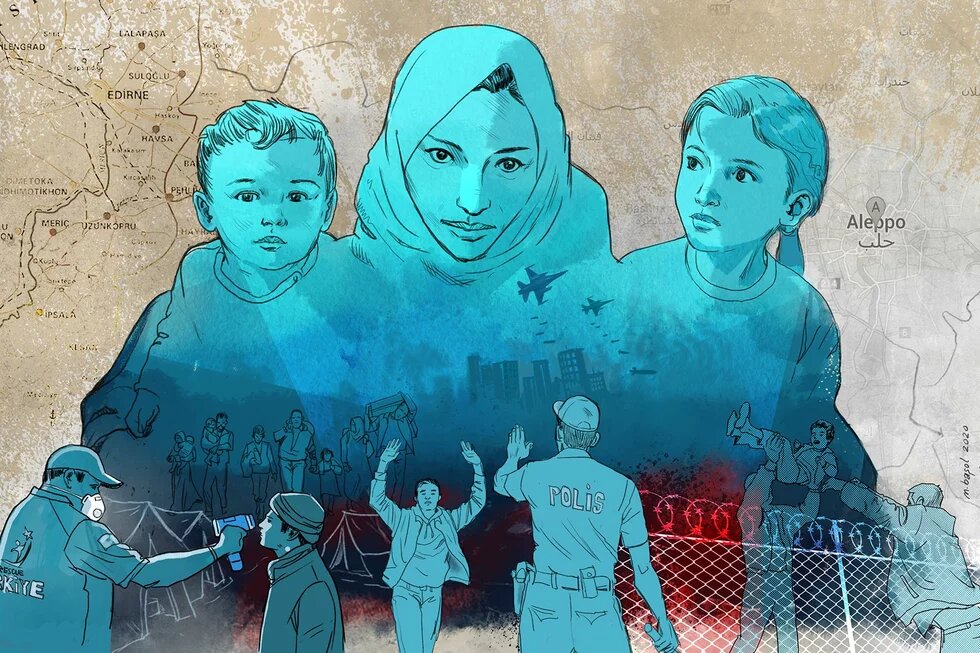

Speaking of the “outbreak” and “migrants”, it is impossible to forget the thousands of migrants who rushed to the land border at Edirne or to the Aegean shores, in hope of crossing into Greece. On the night of February 27th, 2020 and immediately after the killing of 33 Turkish soldiers in Syria’s Idlib province, Pres. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced law enforcement officers would no longer prevent migrants from crossing into Greece. Following this declaration, thousands rushed to the land border in Edirne and camped out near the Pazarkule border gate. Yet, the tide seemed to turn when Turkey confirmed its first Covid-19 case on March 11th, 2020. In its statement entitled “Measures Taken Against Covid-19 With Respect to Migrants Transferred from Pazarkule”, the Directorate General of Migration Management under the Ministry of Interior stated that after the confirmation of the first Covid-19 case in the country, thousands of migrants were provided information about the outbreak via speakers, tents were disinfected at least twice a day, and authorities deployed thermal cameras for elevated body temperature screenings. A while later, however, fearing that crowds in the border region could pose a public health threat, authorities decided to evacuate the area and transferred a total of 5,848 migrants either to removal centers or student dormitories under the General Directorate of Credit and Dormitories (KYK). Meanwhile, footage floated online showing migrants’ tents at the border were deliberately set on fire. Migrants interviewed stated police had forcibly evicted them from the Pazarkule area. Individuals were moved into quarantine for 14 days and monitored by doctors assigned by the provincial directorates of health. The Ministry later announced no cases among this population were detected.

But, how were the material conditions at the removal centers used for the purpose of the quarantine? The Asylum and Migration Commission of the Izmir Bar Association recently published a report titled, “Covid-19 Pandemic at İzmir Harmandalı Removal Centre”, which included a number of allegations including the lack of regular cleaning at the center, poor ventilation, limited hygiene products apart from one bar of soap and a pack of detergent given to persons at the admission, rubbish disposal issues, and limited access to doctor. The report added the current sanitary and material conditions at the centers pose a risk. The Directorate General of Migration Management under the Ministry of Interior, however, rejected these claims and argued the centers are disinfected on a frequent basis and that there was neither overcrowding nor health issues experienced at the centers. In the same report, however, the Izmir Bar Association further noted that 30 refugees and 1 security guard tested positive for Covid-19 at Harmandalı Removal Centre. There is currently no publicly available information on the number of confirmed Covid-19 cases among the migrant and refugee communities in Turkey. I filed a Freedom of Information Request (a FOIA) to the Ministry of Interior in effort to seek responses for the following questions: “What is the number of confirmed Covid-19 cases among migrants?”; “How and which health services can migrants with confirmed Covid-19 cases access?”; and “Are there any plans or measures taken with respect to migrants within the context of the pandemic?” At the time of writing, however, I have yet to receive a reply. The report of the Izmir Bar Association highlighted yet another critical issue. That is, under the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (No. 6458), it isn’t permissible to use removal centers as quarantine areas. The report further noted that “to date, the Ministry of Interior has yet to issue a circular authorizing the use of these centers as quarantine areas”. This may indicate that in an attempt to create a legal basis for the current situation, persons, including those registered under international protection applications in Turkey, might have been issued unlawful deportation orders. As borders remain locked down due to the pandemic, no deportations are currently taking place. However, we will only be able to have a full grasp of the implications of these decisions in the coming days.

At the end of the 14-day quarantine period, some migrants were evacuated from the bordering region and were transferred to their original cities of registration, whereas others were asked whether they wanted to proceed further. Those expressing their wishes to make another attempt in crossing to Greece were left at the centers in Izmir and Çanakkale. However, these individuals later left these provinces for other cities in Turkey, either by their own means or they were transferred by the provincial directorates of migration management. According to information received at the time of writing, there were no migrant groups huddled around Turkey’s Aegean shores, trying to find ways to cross.

I met a group of Iranian, Afghan and Pakistani migrants, a total of 23 people, who spent a month at the Pazarkule border gate in Edirne. The group was later moved from place to place, initially in Malatya for quarantine, then to Kırıkkale, Gebze, Kırklareli, and finally to İstanbul, respectively. When I asked about their wishes, they said: “We want temporary protection. We want to go to the hospital to seek help for our health problems. We want face masks for protection against the virus. Until we manage to cross into Europe, we want these. We need food and we need housing.”

In the time of pandemic, access to healthcare services isn’t the sole issue. Hygiene and nutrition are equally important in supporting a strong immune system. Yet, the living conditions of migrants do not always provide the necessary resilience to confront the outbreak. Employment is a critical factor towards building resilience. However, a large share of migrants work under informal arrangements without social security coverage. While the government continues to issue “stay-at-home” calls, refugees and migrants are among those who have to keep working. This, in turn, increases the risk of infection. But that’s only the half of the picture. Struggling to survive in tough times also means people cannot risk losing their jobs. Fearing a confirmed Covid-19 case might lead to a loss of job and “exclusion”, there might be some refugees and migrants who haven’t reported their health conditions. As Dr. Mardin reiterates, such reporting failures may result in symptoms developing into more severe forms, since people can’t afford sick leave to rest at home. Although the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Services in Turkey may provide financial assistance to persons in need due to the pandemic, only citizens are entitled to these benefits. This, however, exposes migrants to a situation where they can’t afford risking their jobs.

Self-isolation is equally problematic for a migrant with a confirmed Covid-19 case. In larger families, isolating from other family members is particularly more difficult. Dr. Deniz Mardin, of the Association of Public Health Specialists, states that in such cases migrants and refugees who have tested positive for Covid-19 should be provided temporary housing for a month.

The report titled, “The Impact of Covid-19 on Refugees and Migrants”, published by the Association of Public Health Specialists (HASUDER) is one of the most comprehensive sources covering the plight of refugees and migrants in Turkey during the outbreak. The findings of the report indicate that when a person under temporary protection or international protection is diagnosed with Covid-19, due to language barriers, performing filiation has not always been as ideal as it would be, and that there is a need for health professionals speaking Arabic, Farsi or English. The report further reveals that under the “Improving the Health Status of the Syrian Population under Temporary Protection and related Services Provided by Turkish Authorities” project, also known as the “SIHHAT project, videos on individual measures specific to the outbreak were published in multiple languages on social media, and leaflets on maintaining hand hygiene were made available in Arabic both at migrant health centers and online. While the translation of brochures covering basic information on Covid-19 into Arabic is a welcome step, the lack of availability of public service announcements in other languages is certainly a gap.

For some time now, anti-immigrant rhetoric has also been on the rise in Turkey. This makes everyday life more difficult for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Unfortunately, the outbreak of Covid-19 has become yet another excuse exploited by proponents of this rhetoric. That is, migrants fear being stigmatized by the society if they are diagnosed with Covid-19. Yeşim Yasin, a member of the Department of Public Health at Acıbadem University, believes the number of Syrian patients seen by a doctor dropped from 50 per day prior to the outbreak to the current 5 per day level, due to this fear as well as to lockdown restrictions. Polat Alpman, from the Association for Migration Research, on the other hand, states that the securitization of policies hampered migrants’ access to healthcare services, and fear of discrimination has further increased their reluctance in approaching public hospitals where the provision of interpretation services has already been inadequate. The HASUDER report also found migrants with symptoms have belatedly sought medical treatment due to fear of stigmatization and forced evictions, thus showing that these afore-cited concerns were far from being unfounded. For this reason, some migrants feel compelled to resort to “under-the-counter” healthcare providers. There is, certainly, a gender dimension of the living conditions of migrants and refugees amid the outbreak. It is a well-established fact that women and LGBTI migrants and refugees have more limited access to healthcare services even during normal times. Thus, it seems highly likely such access has become even harder these days. As Dr. Yasin points out, there are certain setbacks in the provision of information to migrant and refugee communities. These include, among others, a lack of proper guidance on the necessity to refer pregnant women to hospitals that have not been declared as “pandemic hospitals” and fetal monitoring.

Women’s lives have become even harder under the pandemic as they have to shoulder most of the extra household work on an unequal basis. While global research findings suggest a marked increase in domestic violence, the ruling authority in Turkey has yet to address this issue. This lack of political will had inevitable consequences on migrant and refugee women. So far, the government has yet to adopt measures to prevent the risk of domestic abuse, which is soaring in migrant households, or issue informative public service announcements in this regard.

With the arrival of summer, another noteworthy topic will be migrant seasonal agricultural workers, a lingering social problem. For decades, agricultural workers have been shouldering the heavy burden of Turkish manual labor under inhumane conditions, and all attempts to improve their plight hitherto have regrettably proved unsuccessful. In a recent report entitled “The Virus or Poverty?”, The Development Workshop highlighted the critical need for sheltered tents, the provision of electricity, utility and safe drinking water, as well as sanitary facilities, environmental disinfection, routine disinfection and waste collection. Yet, even if the need for housing and necessary hygiene could be wholly met, there will be a huge question mark over the effectiveness of such measures.

When it’s about migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees, resolving problems has never been easy. Although the Covid-19 is taking its toll on both the rich and the poor, neither opportunities nor challenges are equal. The social and economic impacts of the crisis hit particularly marginalized group hardest. According to Polat Alpman, in times of crisis, states may revert to their primitive predispositions. In other words, political establishments may lean towards taking actions to generate the consent of their citizens, serving the interests of the dominant classes. This also leads to a very justifiable question, touching on the very core of challenges facing migrants, and as a matter of fact, carrying its own answer along with it: “Are immigrants human beings, too? In order to qualify for being a human, they first have to be citizens. A 25-years old migrant youngster vs. a 70-years old senior citizen… If it comes to making a decision about who would get a ventilator, the answer is fairly simple: the citizen. This is the case everywhere…”