2014 is a crucial year for the French Energy Transition. Will the French government really take this major energy, societal and economic change forward and seize the opportunities the Energy Transition offers? Or will it listen to vested interests in nuclear power and fossil fuels and postpone it?

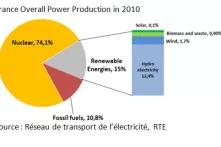

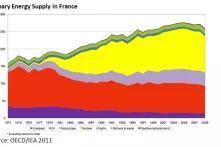

As a candidate to the Presidential Elections, François Hollande committed to decrease the share of nuclear power in France’s electricity production from 75% to 50% by 2025, in the aftermath of Fukushima. Shortly after his election, he also committed to make France “the nation of environmental excellence.”

As a first means to achieve this transformation, the government launched a “National Debate on the Energy Transition,” which lasted 8 months. This debate was meant to serve as basis for a Framework Law on the Energy Transition (Loi de programmation sur la transition énergétique) that would launch the Energy Transition in France (including elements about governance, financing, energy efficiency, renewable energy deployment, nuclear power phase down, competitiveness, and RD&D/innovation).

The French Energy Transition is a challenge, partly because it will cost EUR 20 to 30 billion investments in building retrofitting, the development of renewable energy sources, and the improvement in transport infrastructures. However, most of these investments will be cost effective by 2030 and reduce the French people’s energy bill in the long run. National scenarios based on deep cuts in energy consumption result in net saving up to EUR 159 billon per year (source: SOB scenario studied in the National Debate) . Workable solutions are already tested and implemented on the ground, especially by local authorities, which are still waiting for a national and European governance system that enables them to scale up their efforts, in a country where the tradition is still very much the one of a central state. The Energy Transition is also a job challenge but in France experts have assessed that it would create at least 632,000 net jobs by 2030, especially in the renewable energy and building sectors.

The French National Energy Debate: Lessons Learned

Several thousand people got involved – both at the national and local level – in the National Debate on the Energy Transition, which started at the end of 2012 and ended in July 2013. The main bases for discussion were the commitments to decrease domestic final energy consumption by 50% by 2050 and to bring down the share of nuclear power to 50% by 2025. In addition, France has committed to divide its emissions by 4 by 2050 – this target is inscribed in the law.

Discussions were divided into working groups on:

- Energy efficiency,

- The energy mix,

- The financing of the Energy Transition

- Economic elements (new value chains and renewable energy)

- Governance (including the role of local authorities)

- Distribution networks.

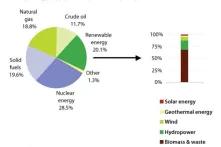

In parallel, an expert group worked on 25 national scenarios to achieve the division by 4 of France’s greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Only a handful of scenarios was consistent with this objective and the phase out of nuclear power - or at least decreasing it to 50%. These scenarios include the ones by: negaWatt , Greenpeace , and the National Agency for Energy and Environment (ADEME) . These scenarios rely on a high share of renewable energy or deep cuts in energy consumptions, or both.

A citizen group was also created and discussions were organised at the local level in different parts of the country.

Overall, the National Debate lacked visibility in the media, which was due to a lack of communications capacity and resources. The Environment and Energy Ministry’s budget has been shrinking every year. While the government has made the Energy Transition a top priority, this shows how little it has been translating its political narrative into action and public investments so far.

At the end of the National Debate, stakeholders agreed upon a written synthesis of the most consensual elements. It contained many interesting proposals. For instance, all stakeholders but the French branch of Business Europe (Mouvement des entreprises de France, MEDEF) supported 3 binding European 2030 targets for greenhouse gas reduction, renewable energy and energy efficiency. Yet, many elements were missing from this text, including specific indications on how France will achieve its target to reduce the share of nuclear power to 50%.

At the last minute, some business organisations and unions refused to draw formal recommendations from this document – to be forwarded to Government and Parliament. MEDEF, representing among other large utilities, was the main opponent. However, many companies do not agree with the current MEDEF position. They include large players in the energy efficiency or renewables sector, who have been asking for a binding EU 2030 renewable energy target. However, these progressive voices are still weak, mainly because of the highly centralised and monopolistic energy system in the country. Unions were also divided on the nuclear issue because some of them are represented by worker federations from the nuclear industry.

An interim Committee of experts, NGOs, unions, and business organisations was established in the summer of 2013 to monitor the law-drafting process. A permanent institution was also created to monitor progress in the Energy Transition. This “National Council on the Energy Transition” includes NGOs, unions, business organisations, experts, and parliamentarians. It is very much linked to state institutions and does not play the role of an independent advisory body.

The draft Framework Law on the Energy Transition

Based on the synthesis from the National Debate, the government was supposed to quickly propose a bill in 2013. This law is still being drafted. In September 2013, François Hollande announced that the adoption of the law was postponed until the end of 2014, while re-affirming the political objective to decrease domestic energy consumption by 50% by 2050.

The proposal should be finalised after the municipal elections of March 2013. And again, some people say it may only be published after the European Elections (end of May) or even September 2014. Then it will to go through a 2-month consultation at the Economic, Social and Environmental Council, a national institution where civil society, research and business organisations are represented. Finally, the proposal will be discussed and amended in Parliament.

A preliminary draft of this law was published in early December 2013. It was very weak on the trajectories for achieving both the 50% nuclear power target and the 50% energy savings target. It was also very weak on the transport sector (first emitting sector in France), as well as the issues of financing and labour market transformation (including training):

- The draft Framework law does not propose a trajectory to achieve the objectives that laid the foundations of the National Debate. It does not include any 2030 milestones for achieving France’s 2050 target for greenhouse gas reductions and therefore does not give any indication of what the future French and European energy and climate policies will look like.

- Transport sector: while the transport sector is the main source of GHG emissions in France, and the cost of fossil fuel for transportation is increasingly high for French households, the draft proposal does not contain any measures among those proposed by citizens and local governments during the National Debate (reform land planning policy, alleviate constrained mobility, favour public and alternative transports, improve the consumption of cars, encourage a real modal shift for commercial transportation, etc.). The only elements that were included are electric and hybrid mobility.

- The financing of the Energy Transition is not addressed in this draft proposal. For instance, the draft law does not suggest the creation of a national financing institution like the German KfW that would offer cheaper loans on significant financial volumes, without deepening public deficits. The draft law does not propose any measure related to local and direct financing, which would help collect private savings in order to invest in local energy projects. Tax reform is mentioned in the draft text, which only refers however to what has already been agreed - the carbon tax that was decided in 2013 and has no fiscal impact in 2014. There are also some concerns around the reference to “financial gains from the performance of nuclear power plants” – this may hide another attempt by the government to extend the lifetime of these plants.

- Local authorities and citizens can and must be an engine of the Energy Transition. Community energy can facilitate the financing, ownership and acceptance of the Transition. However, so far the proposal does not give them a voice and does not give them the financial nor the regulatory means that they should have at their disposal to be plain actors of the Transition.

- Finally, the draft proposal does not mention anything about the urgent needs for professional training and solidarity, which is crucial to promote social acceptance of the Transition. While the Energy Transition will help create several hundred thousands of new jobs in France – requiring new skills and therefore education and training needs – it will also cause job losses in some sectors. Planning the professional transitions and job changes at the regional level is essential.

In mid-March 2013, the proposal was not published yet and many parts of the bill remained empty. The most important elements of the conclusions of the National Debate are being excluded one after the other (for instance, on the 3 climate and energy objectives for 2030). Faced with this lack of progress, French environmental NGOs published their own legislative proposal on the Energy Transition. This proposal relies on ambitious 2030 climate and energy targets at the national level, coherent with ambition EU 2030 targets. These include targets for GHG emissions reduction (45% by 2030), renewable energy development (45%), energy savings (-35%), a determined amount of retrofitted buildings and the phase out of nuclear power. Elements of the proposed law also include a set of clear measures to:

- Promote energy savings in industrial sectors.

- Rapidly improve the energy efficiency of buildings, such as creating a single financial body to help finance the retrofitting of buildings and mandatory insulation of existing homes when large renovation works are carried out.

- Launch the Energy Transition in the transport sector - which has been excluded from most discussions, including: no new road or air transportation infrastructure, reducing speed limits, funding for sustainable transportation.

- Make RES the source of power production by preserving and clarifying support schemes, simplify administrative processes, forbidding non-conventional fossil fuel exploitation in France as well through public investment abroad.

- Finance in the Energy Transition, such as the establishment of a single financial institution, the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies, easier community investment and tools to leverage household’s savings (Livret A) etc.

- Plan and monitor job transitions, and especially training and retraining.

- Improve governance and promote the role of local governments, citizen investment in RES as well as private actors.

For further information on the NGO’s REAL LEGISLATIVE PROPOSAL (in French) click HERE.

Conclusion

France is hosting the UN Climate Change Conference at the end of 2015 – where an international agreement on climate change is supposed to be adopted. Will the French government show that they can be exemplary as a nation and a key EU member state to implement an ambitious Energy Transition and lead the climate trajectory?

In 2014, the French government will show whether it really intends to launch the societal shift that the Energy Transition is, or whether decisions will only be made at the margins. Signals do not look very promising so far. Firstly, France’s position ahead of the European Council on Energy and Climate (20-21 March 2014) is increasingly leaning towards the UK’s single climate target approach – opening doors for nuclear development in Europe. At this summit, the European Heads of State and Government may adopt a framework for Europe’s 2030 Climate and Energy policies. While President Hollande is committed to supporting a binding greenhouse gas reduction target of 40% by 2030 at EU level, his position on binding renewable energy and energy savings targets is still unclear. In addition, 40% emissions reduction is far below what would be needed to achieve the higher end of Europe’s long-term targets (-95% by 2050).

Attempts to reactivate a French-German cooperation on energy (via a French-German Ministerial summit on 19th February) still have to deliver uncertain results. Such an approach may be promising as it may help reduce the strong differences between both countries’ industrial and energy systems and enhance their common features. However it must be based on a political agreement between both countries on an ambitious EU roadmap, and promote cooperation at the local level between SMEs in both countries. This could start on both sides of the borders. This is not the direction taken by bilateral talks so far.

The role of Parliament will be key to more ambition in the various articles of the law. Discussions were ongoing within Parliament on whether the Committee charged with this bill would be the Economic and Finance (more conservative) or Sustainable Development (weaker within Parliament) Committees. Supporters of the Energy Transition supported the creation of an ad-hoc parliamentary committee composed of MPs from various Committees in order to promote policy integration and ownership.