Returning the land to nature and agriculture that restores the soil can create so-called climate landscapes that are able to soak up carbon and water. That helps against droughts and floods, promotes biodiversity, and cools the climate. It also maintains the local and regional water cycles that sustain life on Earth.

Imagine Earth as an enormous living being, its rivers and the groundwater beneath our feet become its arteries and veins. They regulate the planet’s metabolism. The soil is the Earth’s skin. Trees and other plants are like sweat glands – they release water through evaporation, which cools the land surface. But these water cycles are threatened by the destruction of intact landscapes. Deforestation, monocultures, soil degradation, river regulation, and the degradation of peatlands lead to the loss of fertile soils and natural vegetation. Climate scientists have long sounded the alarm about global tipping points. The disruption of water cycles by soil degradation and the loss of natural vegetation may constitute a tipping point, one that irreparably damages vital processes that make large parts of the world green and habitable.

Such a tipping point can be averted through decisive action. More vegetation and fertile, humus-rich soils could cool and revitalise entire landscapes. Water can literally be cultivated. Plants consist mainly of water, and their leaves transpire enormous amounts of moisture, which then becomes part of the water cycle again. On a summer’s day, a single large tree transpires several hundred litres of water, generating as much evaporative cooling as two air conditioning units.

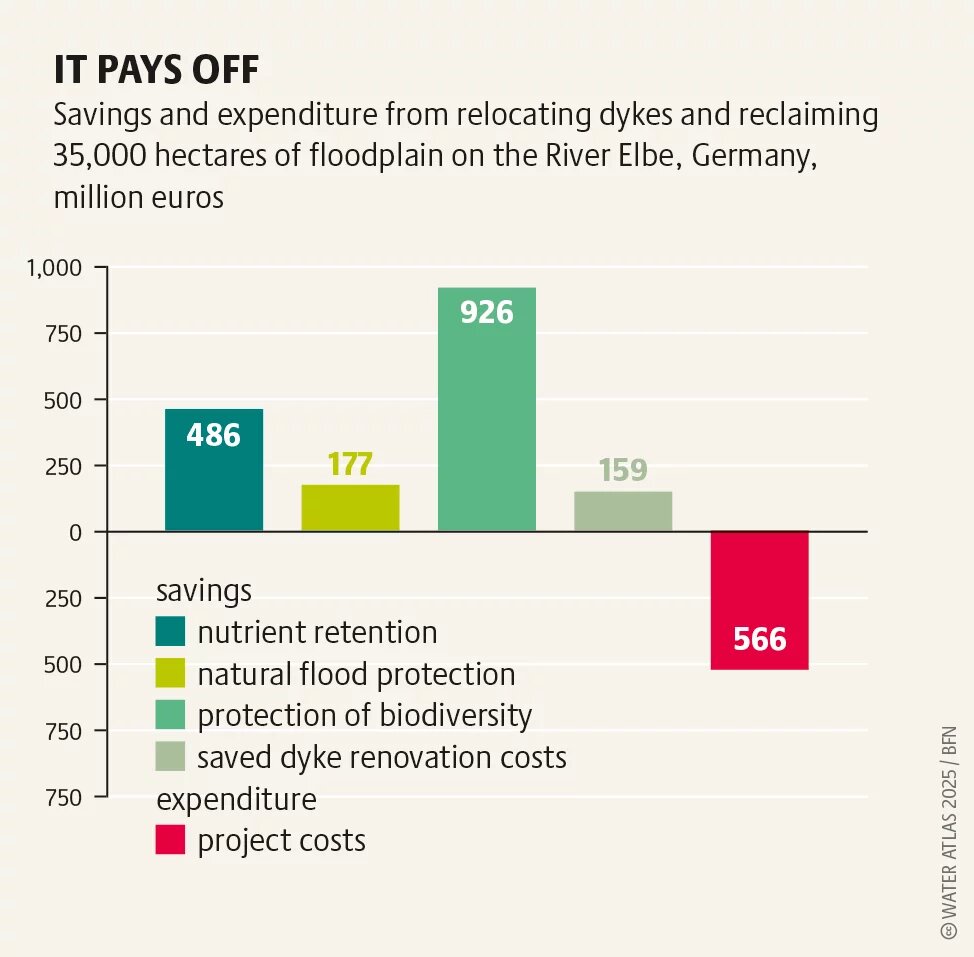

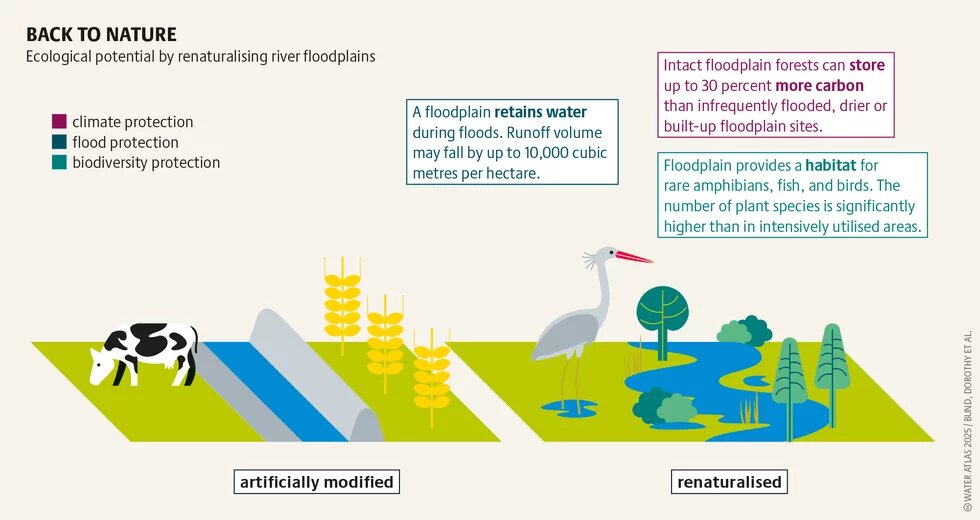

This can work only if the rain that falls can soak into the soil and can stay there for as long as possible. The key to this is slowing down the water cycle. Rivers and streams that have been straightened, obstructed, or canalised must be permitted to meander and overflow their banks once more. In cities, as much of the surface as possible should be freed of concrete and asphalt to let rainwater seep in. The richer the soil is in humus, the better: the more water it can store.

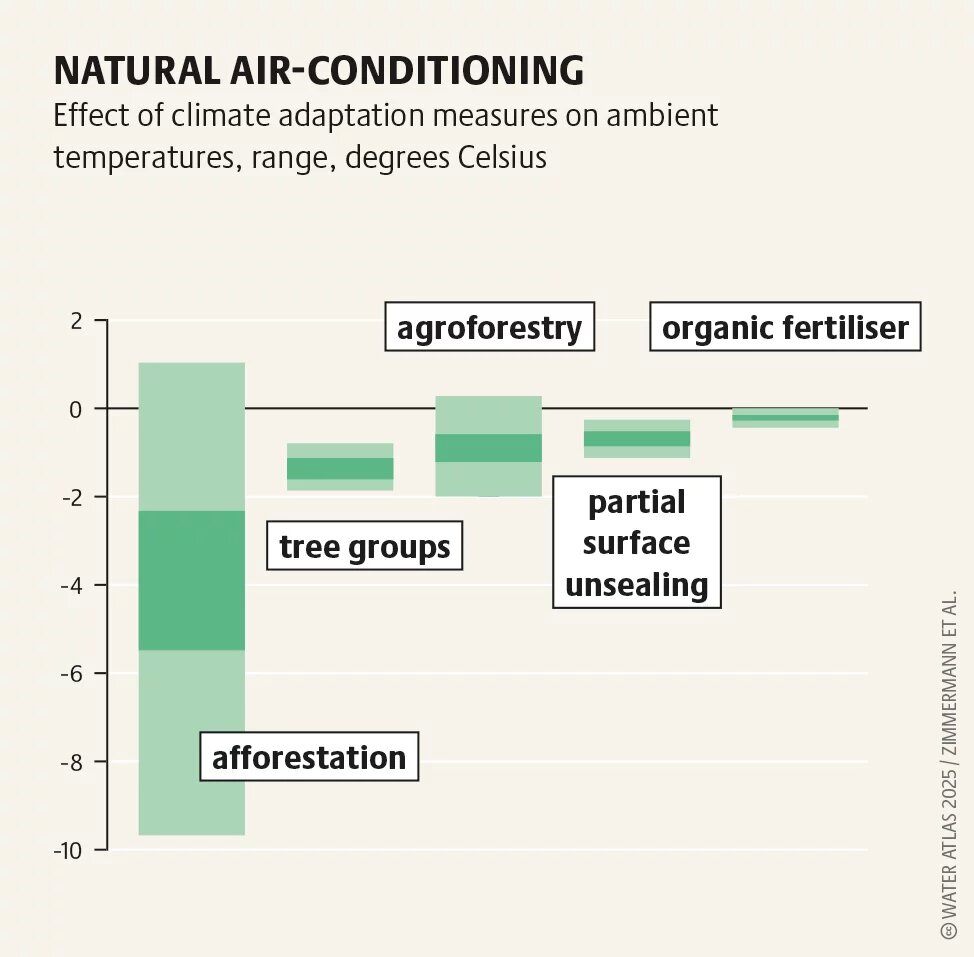

In farming that means keeping the soil surface covered to protect it from evaporation and erosion. One way to do this is by undersowing: sowing a second crop a few weeks after the main crop; this undersown crop will cover the soil after the main crop is harvested. Other possibilities are planting cover crops, avoiding ploughing, and applying compost. Agroforestry, which integrates trees and hedges into fields, can build up the soil, slow down the flow of water, and store it. These measures have huge effects: areas planted with trees can cool their surroundings by several degrees, break the wind, and increase biodiversity by providing habitat for birds and insects. Planting trees and shrubs can even increase the total output by producing wood, berries, and nuts that can be harvested.

Natural climate protection has huge potential to restore disrupted cycles and reverse environmental damage. The renaturation of just 15 percent of global ecosystems could prevent 60 percent of species extinction as well as help stop around 300 gigatonnes of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂) from being released into the atmosphere. But such measures can only help tackle the climate crisis if other climate actions are also implemented. Carbon storage projects cannot replace the phase-out of fossil fuels.

Protecting and rewetting peatlands should be given priority. Around 95 percent of Germany’s peatlands have been artificially drained for agriculture, forestry, and peat extraction. Renaturing the four million hectares of wetlands that have lost their natural functions as a result of human interventions would enable them to store between 100 and 400 gigatonnes of CO₂. The figure of 400 gigatons is roughly ten times the current annual global greenhouse gas emissions. Renaturation also has a positive effect on species protection and water storage. The rewetted peatlands could still be used for agriculture. Paludiculture possibilities include grazing by water buffaloes or growing reeds for use as building materials.

Regenerated water cycles, more vegetation, and fertile soils can revitalise whole landscapes to adapt to the climate crisis. Examples are restored forests, meadows, wetlands, arable land which integrates agroforestry, and rewetted peatlands. And last but not least: sponge cities, where unsealed surfaces absorb rainwater and so prevent flooding, and where greened rooftops cool the microclimate. A 2024 study has revealed that forests in the eastern United States cool the land surface by 1 to 2 degrees Celsius annually, and by 2 to 5 degrees Celsius at midday during the growing season. Young forests between 20 to 40 years old have the strongest effect. This cooling also lowers near-surface air temperatures by up to 1 degree Celsius compared to nearby non-forest areas. Analyses of historical land cover and temperature trends show that areas surrounded by regrowing forests were up to 1 degree Celsius cooler than nearby regions without land cover change.

Developing such climate landscapes requires a clear and reliable political framework. Agricultural businesses that specialise in paludiculture require planning security and financial incentives. At the same time, value chains must be developed that involve the construction industry, for example, and that promote the sale of sustainable products made from peatland plants such as reeds and peat moss. That would restore water cycles, sequester carbon, cool the Earth and allow biodiversity to flourish. In turn that would create valuable spaces for humans, plants, and animals alike.