Access to clean water is a human right. But with the climate crisis and population growth, water is becoming an ever-scarcer resource – over which different groups may compete fiercely. International agreements can help promote cooperation rather than conflict.

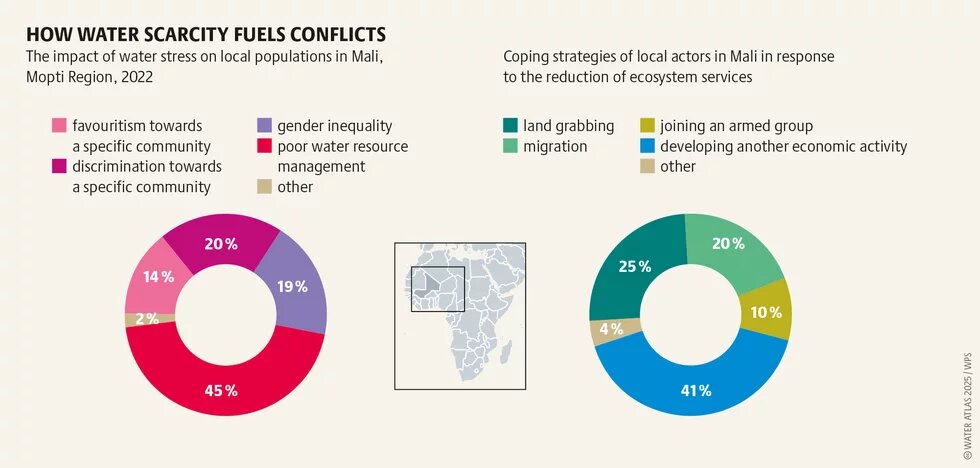

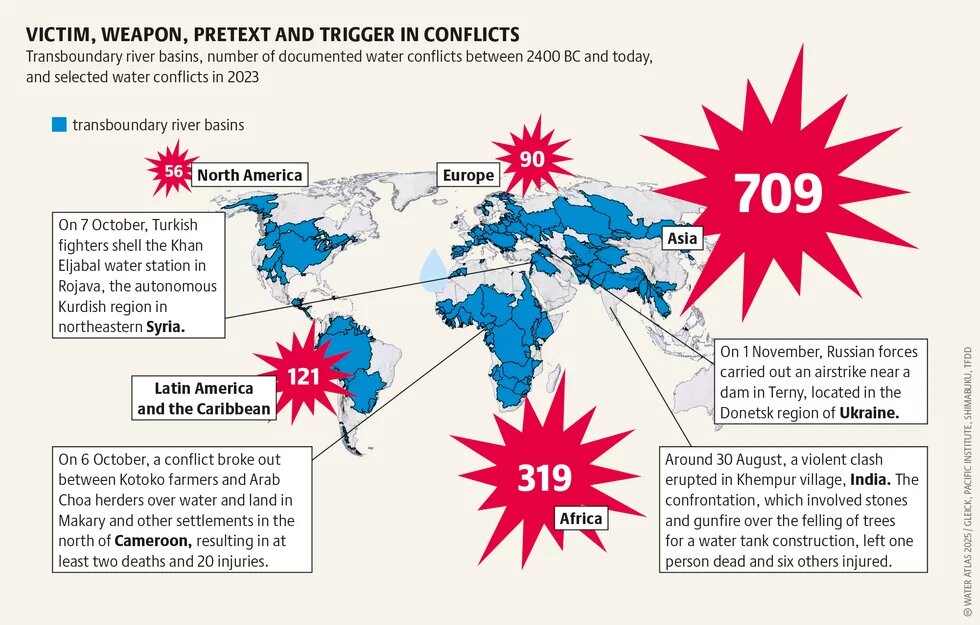

Disputes frequently erupt over the distribution, use, and protection of water resources. Examples abound all over the world. In the Inner Niger Delta in Mali, there have been violent clashes between herders and farmers competing for water, which is becoming scarcer because of the climate crisis and newly built dams on the upper reaches of the river. In Iran, water shortages arise due to the climate crisis and are exacerbated by mismanagement. The result is tensions between people in rural areas and those in the cities. The Iranian police routinely suppress protests against the government. In armed conflicts, water infrastructure often becomes a target: armies and terrorist groups deli-berately destroy irrigation canals, desalination plants and dams, as happened in Iraq, Syria, Gaza and Ukraine in recent years.

The situation gets especially complicated if the rivers, lakes or groundwater bodies in question cross international borders. Worldwide, there are in fact 313 such transboundary surface water bodies, almost 600 groundwater reserves, and around 300 wetlands. These cannot be administered by one state alone, and in such cases the economic and security interests of several states may collide. The Nile is an example: in 2011, Ethiopia started building a dam on the upper reaches of the Blue Nile to generate electricity to provide the Ethiopian people with clean power. But far downstream, Egypt sees this as an existential threat to its own water supplies, 97 percent of which depend on the Nile. For years this has given rise to diplomatic tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia, as well as with Sudan, which lies between them.

The dispute over the Syr Darya River in Central Asia also highlights the significant conflict potential of transboundary rivers. The core issue is that the Toktugul dam, controlled by Kyrgyzstan, seeks to release water during winter for hydropower production, while Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan depend on summer water releases for irrigation, particularly for cotton cultivation, which is a major part of Uzbekistan’s economy. Disagreements over the timing of these discharges have brought the countries to the brink of conflict following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Tensions escalated as Kyrgyzstan repeatedly reduced water outflows to maintain reservoir levels. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan accused Kyrgyzstan of using water as a political bargaining tool.

The loss of state institutions can make water management less efficient. In Afghanistan, the gradual loss of power by the previous government meant that ageing infrastructure was no longer maintained and eventually ceased to function. As a result, it was no longer possible to ensure the equitable distribution of water. The Taliban succeeded in taking control of an increasing number of local water-management institutions, such as the so-called mirab system. This also contributed to the Taliban’s recruitment success in the later 2010s, which ultimately, and after all, brought them back to power in 2021.

Despite all this, the modern era has not yet experienced an inter-state war directly over water. Research shows that conflicts over water are actually fairly rare, at least when compared with cases of cooperation. A systematic analysis shows that only 28 percent of all interactions between states over water are conflictual in nature. They are even less likely to turn violent.

However, the data also show that conflicts over water have been on the rise in recent years. Water is often one of several different factors that contribute to a conflict, and it can lead to an escalation of the situation. That is the case in the Lake Chad basin in Central and West Africa, where ethnic and religious tensions fuel conflicts between different groups of water users.

States and other institutions have meanwhile created legal and political mechanisms to help organise the distribution and use of water in a peaceful way. Global water agreements set legal standards and offer states a framework to guide their actions. Over 800 intergovernmental agreements regulate the distribution of water, pollution, and fisheries. The International Court of Justice and the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague also serve as places for arbitration. In 1997, for example, they mediated a dispute between Hungary and Czechoslovakia – a country that had ceased to exist – over the Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros dams on the Danube. In 2013 they led negotiations between India and Pakistan over a dam on the Kishenganga, a tributary of the Indus. Both sets of negotiations were able to prevent an escalation and stimulated all parties to work together.

History shows that for both sides, cooperation brings long-term benefits that would be unattainable through the unilateral use of the cross-border water resource. Since the 1970s, cooperation between the countries along the River Senegal in West Africa has permitted the joint construction of two dams that enable year-round irrigated farming, deliver electricity to neighbouring countries, and facilitate navigation. None of the states would have been able to finance these projects alone. This is one of many examples of what is possible if one shares water instead of fighting over it.