After years of setbacks, the UK is finally pushing ahead with two carbon capture and storage projects. While there is scepticism about the technology, says Ros Taylor, its supporters argue the cost is justified if the UK means to reach net zero.

“It would be terrible if it were the best idea ever that was never given a chance,” the late MP Bob Blizzard told the House of Commons in 2004 — the first time that carbon capture was mentioned in Parliament. Two decades later, carbon capture and storage (CCUS) has just been given another big chance worth up to £21.7 billion over the next 25 years.

But not everyone has been convinced. The Green Party of England and Wales, Greenpeace and the prominent environmental campaigner George Monbiot are among the opponents. For them, CCUS is a bad idea that props up fossil fuel industries.

Their objections are threefold. First, they argue the technology is unproven; second, that it is very expensive; and third, that it will encourage fossil fuel companies to carry on emitting carbon dioxide, rather than getting out of the extraction business and switching to renewables.

They point out, correctly, that previous CCUS projects in the UK have failed. The first project, which would have captured CO2 in the Scottish port of Peterhead and stored it in the Miller oilfield, never got beyond the conceptual stage because of a lack of funding. The government then launched a CCUS competition but cancelled it in 2011 after negotiations failed. A year later, it tried again with two preferred bidders. This too went nowhere, largely because the department involved never agreed with the Treasury how much financial support would be available.

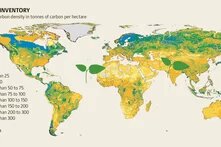

Yet as a Commons committee report argued in 2014, the UK is geologically and geographically ideally suited to CCUS. Five offshore storage sites — four in the North Sea and one in the Irish Sea — were identified years ago as suitable for sequestering CO2. The problem is the cost of developing the technology and confidence in the government to shoulder the risks. “Many stakeholders think the government needs to carry more risk if it is to enable CCS to be deployed affordably to consumers,” said the National Audit Office after the failure of the second competition.

That lesson has been learnt, and the new Labour government has pushed forward with plans for a new hub in Teesside in north-east England. It will collect and pipe CO2 to the Endurance store and is a partnership between BP, Equinor and Total Energies. A second site in Merseyside will use a store in the Irish Sea. Both will also use to CCUS to produce blue hydrogen.

Fourth time lucky?

But will this time be different? Dr Steve Smith, the executive director of CO2RE at Oxford University, thinks so. “It’s the first time that contracts have actually been signed to go ahead with CCUS in the UK. This time around it seems we’ve got a government that is taking this seriously. They’ve been a lot more proactive and done more work on the risk sharing.”

Esin Serin, a UK policy fellow at the Grantham Research Institute at the London School of Economics, agrees. “It’s a necessity, not an option, if the government is going to reduce to net zero.”

“The difference is that the investments are now founded in the budget, there’s clear buy-in from the Treasury, and the government seems to grasp the fact that it’s a priority within an industrial strategy for growth. They’re looking at it as an economic opportunity.” She adds that the investment frameworks are better designed this time and have been developed in partnership with the private sector. “They’re separate for the transport and storage of CO2, and this gives revenue certainty for CCUS.”

The Low Carbon Contracts Company is a counter-party in the business models. It was set up a decade ago to facilitate investment in renewables using Contracts for Difference. Essentially, it reduces the financial risk for the companies involved in carbon transportation and storage.

Part of the rationale for investing in CCUS is that it will both boost struggling post-industrial areas — both Merseyside and Teesside suffered large-scale unemployment in the 1980s from which they have never fully recovered — and provide opportunities for North Sea oil and gas workers to retrain as their industry shrinks. “They match up to the levelling up agenda [a drive to improve the economy outside London and the south-east]. There is a natural fit,” says Smith. The Unite trade union has welcomed the CCUS investment, although it complains that there was nothing for Scotland. Reviving ailing industrial centres is also less controversial than building new energy infrastructure in rural Britain. Even in remote parts of Scotland, some locals are fighting plans for new pylons.

The role of fossil fuel companies

Still, many green campaigners are deeply unhappy that the Treasury is committing money that could be spent on developing renewables or rewilding. “It licenses continued fossil fuel production,” says George Monbiot, who would rather see green hydrogen (generated from renewable energy) than blue (from CCUS). Greenpeace also argues it incentivises fossil fuel companies to continue extracting.

The counter-argument is that crucial parts of the UK economy, such as cement and steel manufacture, are impossible to decarbonise completely. The Climate Change Committee has predicted it will be impossible for Britain to reach net zero by 2050 without using carbon capture.

“We really need to make sure we need to do all of those things together,” says Smith. He says that by 2050 most carbon capture will need to be from biomass and directly from the air rather than from fossil fuels. At the same time, implementing the Committee’s recommendations would mean a far bigger switch to heat pumps and electric vehicles, and Britons cutting their meat consumption by a third.

He says fossil fuel companies are not as keen on CCUS as some environmental campaigners believe. “Compared with the huge profits they make from their current business model, when they talk about doing CCUS they end up often having to have very deep contractual conversations for low promised returns. Currently there’s no easy contractual template to follow, and governments even turn around and renege on the discussions.

“It’s a much more sketchy, much lower reward proposition.” Nonetheless, “if I was a forward-thinking oil and gas company, I’d be putting a lot more money into CCUS.”

At the same time, Serin says, CCUS needs to be used judiciously. “There are sectors where it will be a necessity but in others it will not be needed so much. It would be a disaster to lock us up into avoidable gas consumption.” She does see a role for hydrogen, “but over time I’d expect green hydrogen costs to come down rapidly.”

The CCUS plans have attracted very little attention outside Teesside and Merseyside. Many Britons are completely unaware that carbon can be stored under the seabed in disused fields. Media coverage tends to be sceptical or non-existent.

Given the history of CCUS projects, and the fact that it will be 2028 at the very earliest before any carbon is captured, perhaps it is best to be circumspect. “It’s not something that can be built incredibly quickly at incredibly low cost,” says Smith. But after so many false starts, investors are newly confident that the government is serious about implementing the technology.

Read more on carbon capture and storage in our Energy Transition Blog.

The views and opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.