The world’s soils store more carbon than its forests, and this storage capacity is increasingly discussed as a contributor to climate protection. Tradable carbon credits were designed to incentivise the build-up or retention of carbon in the soil. However, they may in fact undermine efforts to reduce emissions.

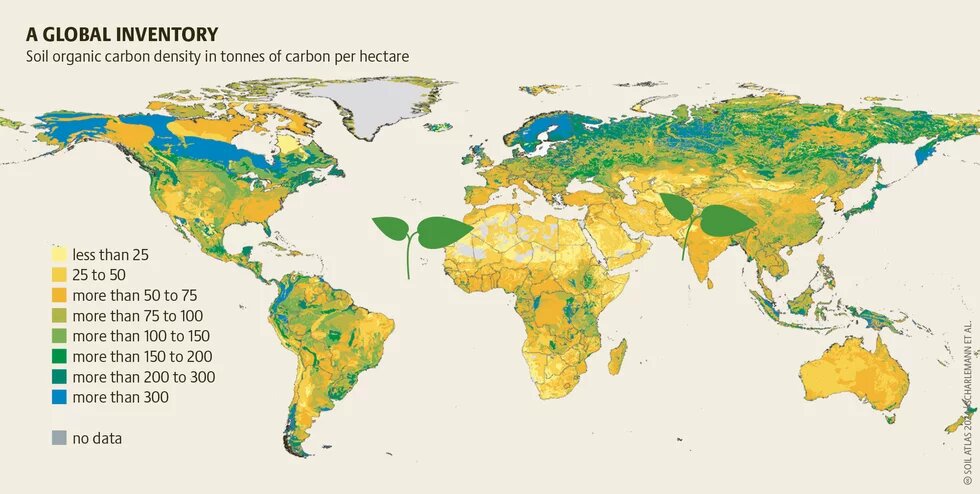

Soils contain vast amounts of carbon, mainly in the form of humus, the organic matter formed from decomposed plants and animals. It is estimated that the top 30 centimetres of the Earth’s soil contain close to 700 billion tonnes of carbon, exceeding the 560 billion tonnes stored by plants, especially in forests. As a natural sink for the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂), soils are an important factor in climate mitigation policy. Modelling suggests that between 2 and 5 billion tonnes of carbon could potentially be sequestered in soils each year. However, this potential depends on future land use and the progression of the climate crisis. Today, in many parts of Europe, soils are net carbon sources: they emit more carbon than they absorb. For example, drained peatlands are significant carbon emitters.

Reducing emissions must remain the priority for achieving the Paris Agreement’s climate goal of limiting global temperature rise to well below 2 degrees Celsius. In addition to deep emission cuts, sequestering carbon in soils can play a limited but important role in climate policy. Beyond climate mitigation, building up carbon in soils is crucial for adapting to the climate crisis and restoring healthy soils. Consequently, scientists, practitioners, and policy makers are increasingly exploring the potential of soils as natural carbon sinks. One such approach is carbon farming, which encompasses a range of activities that aim to increase the amount of carbon in soils and forests. Practices include improved crop rotation, direct seeding, mulching, rewetting drained peatlands, planting trees on deforested land, as well as agroforestry—an approach that integrates trees and crops on the same area of land.

Carbon farming is expected to be financed through the sale of so-called soil carbon credits, which would compensate for the emission of greenhouse gases like CO₂. The European Union (EU) is currently attempting to outline a legal framework for carbon offsetting, including through storing carbon in soils. The principle is simple: farmers commit to increasing the carbon content of their soil over a certain period of time using specific methods. For each tonne of CO₂ they store, they receive a carbon credit. Companies can then purchase these credits to offset their own emissions and claim their products or services as climate neutral. But this approach to carbon offsetting is controversial. Research has shown that many companies rely heavily on carbon offsetting to meet their climate action goals. By buying credits, they can continue emitting greenhouse gases as usual while still claiming to be climate neutral—a practice often criticised as greenwashing.

Carbon offsetting is based on the idea that each credit represents a tonne of carbon that is stored in the ground. However, a precise and standardised method for measuring soil carbon sequestration does not yet exist. Soil organic carbon content can vary greatly, even within the same field, and it is never certain that the stored carbon will remain in the soil indefinitely. To genuinely compensate for CO₂ emissions, the carbon would need to stay in the ground for the same period of time that CO₂ remains in the atmosphere. But long-term or permanent sequestration cannot be guaranteed, as the carbon content of the soil is easily reversible. Changes in cultivation practices or extreme weather—occurring more frequently due to the climate crisis—can release the stored carbon at any time.

Criticism of carbon trading schemes has led to new proposals, such as retaining a portion of the sequestered carbon as a reserve rather than selling the entire amount as credits. However, experience with the trade of forest carbon credits has shown that this approach also entails serious risks. In California, forest fires have already consumed up to 95 percent of carbon credits reserves in less than a decade—reserves that were intended to compensate for carbon releases over the next century. As climate change continues to intensify, the likelihood that sequestered carbon will be released back into the atmosphere increases. The EU hopes to tackle this problem by creating carbon credits that expire after a certain period of time. This approach will create new challenges in overseeing the use of credits.

In countries like Australia and Scotland, trading soil carbon credits has driven up land prices, making it harder for young farmers and smallholders to access land. Years of experience with forest carbon credits have also demonstrated that the potential for financial gain from selling carbon credits has incentivised land grabbing in various regions. In Uganda, thousands of people have been displaced for tree plantations established by a Norwegian company. The international trade in carbon credits thus runs the risk of perpetuating neo-colonial structures, allowing companies from the Global North to maintain their climate-damaging business models by appropriating land and soil from communities in the Global South.

A robust humus layer is essential for resilient ecosystems that ensure food security, support biodiversity, and mitigate droughts and floods. However, soil protection measures should neither replace measures for deep emission cuts, nor restrict human rights or people’s right to land. It is crucial that any efforts to enhance soil carbon sequestration are integrated into broader strategies that prioritise social equity, environmental sustainability, and the long-term well-being of communities.