Soil plays a major role in protecting the environment. It serves as carbon reservoirs, the plots into which trees are planted, and a steward for producing climate-neutral fuels. But land-intensive climate action can give rise to conflicts and erode people’s rights. Even so, there is yet to be a resolution for this mounting global challenge in sight.

At the heart of the Paris Climate Agreement rests the goal of limiting the average global warming to 2 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial era. Such efforts aimed at realizing a climate-neutral economy are founded on two principles. First, greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide (CO₂), must be significantly reduced. Second, these climate-damaging gases must be removed from the atmosphere and sequestered. The central goal of this combined approach is to achieve net zero, which requires striving to both curb emissions and compensate for those that may be unavoidable by storing them in trees, soil or by other means. Greenhouse gases, for example, could be sequestered using the carbon capture and storage (CCS) process. In the CCS process, CO₂ is removed during industrial processes, transported, and stored in underground reservoirs instead of being released into the atmosphere. Other potential options to reduce greenhouse gases, which environmental associations favour, centre on nature-based carbon removal: rewetting peatlands, reforestation and afforestation, and sustainably managing pastures and agricultural land.

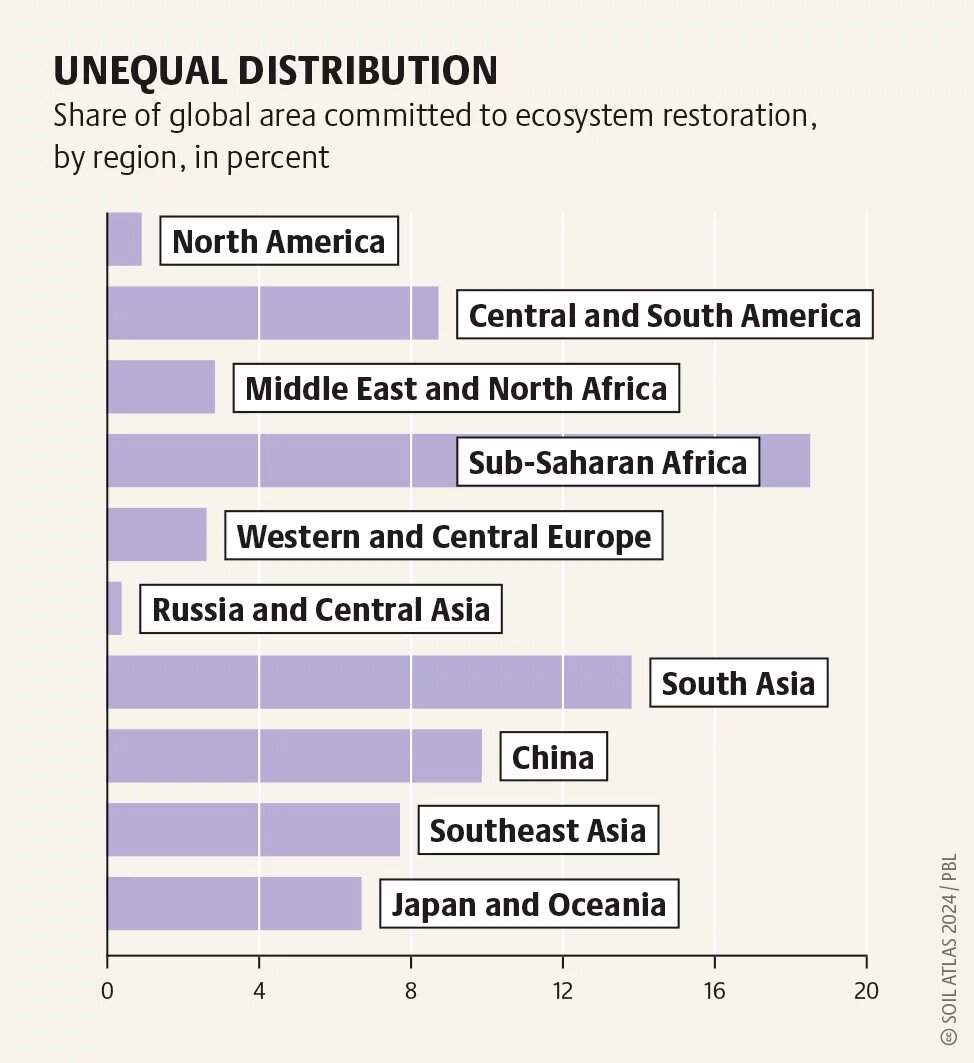

As large-scale CO₂ offset measures, governments and firms employ similar nature-based carbon removal tactics, such as protecting forests and planting trees on fallow land. Large German corporations are also investing in projects that depend on land-intensive climate action to offset their emissions. For example, cosmetics producer Beiersdorf promotes such initiatives in Paraguay. Moreover, nearly all Member States party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change have agreed to national climate commitments that include nature-based climate action. However, meeting these pledges require 1.2 billion hectares of land – almost three times the total area of the European Union.

Indeed, to make progress on achieving the net zero target, over 630 million hectares of land is expected to undergo land-use change and over 550 million hectares of degraded ecosystems must be restored. This overreliance on land-based carbon removal poses risks for local communities. For example, land-use change could mean converting agricultural land into forest, which can subsequently erode pre-existing land rights for farmers, herders, and Indigenous Peoples. More-over, conflict arose between local communities during prior land-intensive climate projects, which aimed to minimise emissions released by deforestation and forest degradation. In light of this, governments must uphold their human rights commitments, which entail protecting the land rights of local communities and Indigenous Peoples. At its essence, implementing net zero measures responsibly therefore requires well-functioning state and civil society structures.

Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are heralded as countries with the greatest potential for nature-based climate action. However, state institutions in rural areas of both countries are often not sufficiently equipped to manage the land demand arising from climate projects. In addition, the countries in the Congo Basin and Amazon are home to massive rainforests, often described as the Earth’s lungs. However, forestry projects in these areas repeatedly violate the rights of local communities and Indigenous Peoples, hindering their access to forests: a critical source of food, traditional medicinal plants, and cultural sites. Furthermore, there are recurrent cases of violent expulsions and targeted killings of land rights defenders.

As it stands, there is no comprehensive international approach that would regulate the extraordinary land demand arising from climate commitments. Future climate policy must account for this by featuring land rights as an integral component. This will ensure communities made vulnerable by these commitments are protected, as well as globally agreed climate goals can be achieved. As many studies have shown, secure land rights provide an incentive to sustainably use and manage land and forests. Without those rights, that incentive is lost. So too are the hopes invested in the success of nature-based climate action.