Modern farming techniques were introduced to India during the Green Revolution of the 1960s to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population. However, the overuse of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, alongside the cultivation in monocultures, severely damaged soil health. In response, many farmers are moving back to alternative soil management practices. Political support for this transition is growing, but requires more flame to ignite change.

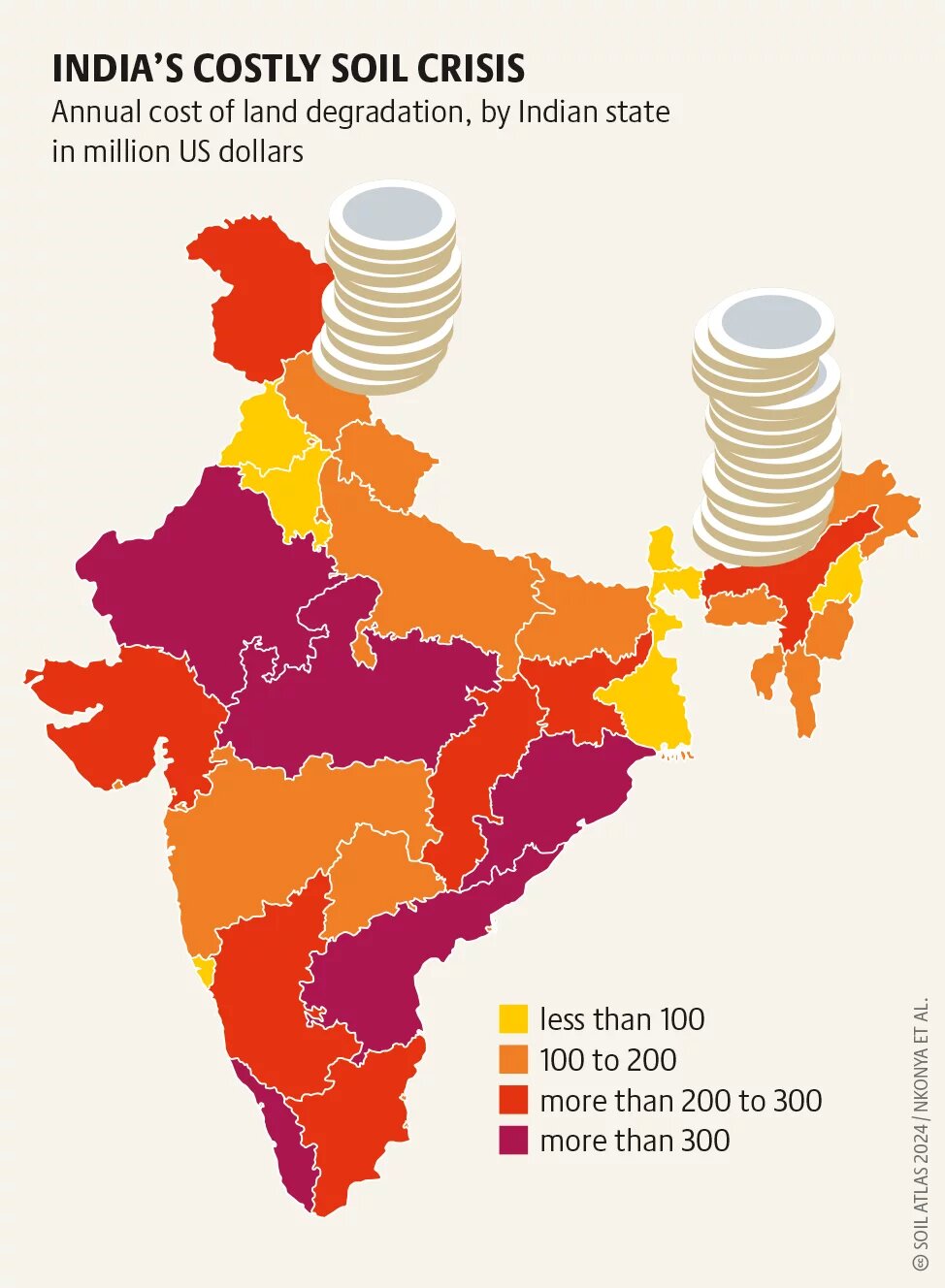

Over the past 50 years, India’s agricultural production has almost tripled, even as the area of available farmland has decreased due to urbanisation, infrastructural development, and industrialisation. However, there is a heavy downside to the intensification of agriculture. The excessive use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides had negative impacts on India’s soil. It is estimated that 37 percent of India’s land is affected by degradation. Furthermore, a study of 50 million soil samples collected across India between 2015 and 2019 found that over two-thirds of samples were deficient in key nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, and 85 percent contained too little organic carbon for functional soil ecosystem. Reduced soil fertility hinders plant growth, leading to knock-on effects such as erosion and increased greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, depleted soils respond poorly to the application of chemical fertilisers. For example, in the 1970s, India’s farmers produced 15 kilograms of grain per kilogram of fertiliser used; by 2015 that ratio has fallen to 5 kilograms of grain per kilogram of fertiliser.

Farmers across India are now turning to a range of sustainable methods to revive their soils. Sustainable soil management (SSM) aims to maintain or improve soil health, productivity, and ecosystem functions while minimising negative environmental impacts. Various plant- and animal-based techniques can be used to improve the biodiversity, structure and fertility of the soil: fertilisers such as compost and manure, bone meal and fish emulsion, cover crops such as beans, and mulching with plant residues. Unlike chemical fertilisers, organic fertilisers nourish the soil microbiome and help crops grow without harming the environment. Practices like minimum tillage, hedge planting, and combining trees with crops in agroforestry systems, not only help combat erosion but can reverse or mitigate soil carbon depletion, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and conserve water. Healthy soils also increase the resilience of agricultural systems to climate-related shocks and stresses.

Organic farming methods are also on the rise. While the share of total farmland under certified organic methods is still low, it has grown rapidly in recent years, from 0.7 percent in 2015 to 2.7 percent in 2022. In terms of numbers of producers, India leads the world, with over 1 million organic food producers. While the total number of uncertified organic growers is unknown, some numbers do exist. For example, community-managed natural farming, which emphasises sustainable and chemical-free agricultural practices, covers about 6 million households and 6 million hectares of farmland in just one state, Andhra Pradesh.

Policymakers have noted this trend and have begun taking steps to encourage the transition to SSM. For example, in 2015 the Government of India launched the Soil Health Card scheme. This service advises farmers on the types and amounts of fertilisers to use in order to safeguard soil health. The scheme reduced the use of chemical fertilisers by 8 to 10 percent while increasing productivity by 5 to 6 percent.

The use of chemical fertilisers is declining. Meanwhile, the organic fertiliser industry in India has experienced significant growth in recent years; production more than doubled from 28 million metric tonnes in 2016 and 2017 to 61 million tonnes in 2019 and 2020. This market is expected to grow at an annual rate of 13 percent until 2030, with revenues projected to reach 826 million US dollars. Demand for organic fertilisers is driven mainly by changes in consumer behaviour, as more Indians favour sustainably sourced food.

The government, non-governmental organisations, farmer cooperatives, and community-supported programmes are helping farmers learn about and use organic farming methods. But problems persist, including limited availability of inputs such as seeds, insufficient composting, and fragmented landholdings. Chemical fertilisers are still being heavily subsidised, and erosion, salinisation, and nutrient depletion continue to threaten soil health.

A multi-pronged approach is needed to address these problems: more and better training for farmers; improved research on sustainable land management including long-term impact assessment studies; the adoption of advanced technologies such as remote sensing for resource management; and the application of the best practices in organic farming. Changes are also needed at policy level, including the transfer of subsidies from chemical to organic fertilisers, financial incentives for farmers who implement SSM, and technical assistance for farmers transitioning to conservation tillage. Yet, policies need to translate into action. Concerted efforts by government, research institutions, and farmers are needed for the long-term health of India’s soils.