Soil – sometimes referred to as the planet's skin – takes hundreds or thousands of years to form, making it a non-renewable resource on a human timescale. It provides the basis for human life, and its health affects the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe.

Soils are composed of minerals, organic matter, gases, and water. Organic matter includes living organisms such as bacteria, fungi, earthworms, insects, microbes, and plant roots, as well as decomposing material such as animal waste and plant residues. Soil particles are formed through the gradual weathering and breakdown of rocks and minerals. These particles combine with decomposed organic matter and atmospheric depositions to create an ecosystem that supports plants, animals, and humans. Soil types and properties are highly diverse, reflecting the wide range of landscapes and climates on Earth. Nearly two-thirds of all living organisms are found in soils.

Roughly 95 percent of the world’s food is grown on soils. Healthy soils function variously as a sponge, a buffer, and a filter that traps pollutants like heavy metals and pesticides. Within the soil, millions of microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, work tirelessly to break down harmful substances. These microbes can transform dangerous chemicals into less toxic compounds, thus making our food safer.

Soils also play a major role in nutrient cycles, storing, transforming, and recycling the elements essential for life, such as calcium, carbon, magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and sulphur. Soil nutrients originate from decomposed organic matter, weathered rocks, and atmospheric deposition. When plants grow, they absorb these nutrients from the soil through their roots. One of the most critical nutrient cycles supported by soils is the nitrogen cycle. Nitrogen is essential for plant growth, yet most plants cannot harness atmospheric nitrogen. Soil microorganisms convert atmospheric nitrogen into usable forms, like ammonia and nitrates. Plants absorb these nutrients to produce essential molecules. When plants and animals die, nitrogen returns to the soil through decomposition, completing the cycle.

Soils also contribute to flood regulation and water quality by storing, filtering, and purifying rainwater, and making it available to plants. Excess water filters down into aquifers. However, soil compaction, caused by overgrazing and the use of heavy agricultural machinery, hinders water infiltration, leading to run-off that causes floods and landslides. As droughts and water scarcity occur more frequently, sustainable soil management becomes increasingly important: healthy soil can store 250 litres of rainwater per cubic metre. A one-percent increase in organic matter enables soil to retain an additional 150,000 litres of water per hectare. Furthermore, healthy soils are a prerequisite for clean air, as water and wind erosion lead to dust and sand being carried by the wind, diminishing air quality.

Soils are also indispensable in the fight against climate change. They store more carbon than vegetation and the atmosphere combined. Carbon is absorbed from the atmosphere by plants and then stored in soils through the plants’ roots. The top 30 centimetres of soil alone hold approximately 694 gigatonnes of carbon. If soils are not managed properly, this carbon may be released into the atmosphere as the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂). For example, as a result of peatland drainage and forest clearing for agricultural use, cultivated lands have lost between 50 to 70 percent of their original carbon stocks.

Soils, and the plants and animals they support, not only sustain us physically but also enrich our wellbeing and culture in many ways. Soils offer aesthetic and recreational value for people to admire the wealth and beauty of nature. There is growing evidence to support the therapeutic value of direct human contact with soil. A therapy known as grounding, or earthing, has been shown to support wellbeing, relieve mental and emotional distress, and produce positive physiological changes. In many cultures, the soil itself holds profound spiritual and religious significance, serving as the foundation for belief systems. The Indigenous Peoples of the Andes regard soil as a living entity through the spiritual concept of Pachamama. Before undertaking any activity involving soil, they hold a ceremony to feed and honour the living soil. Moreover, soils serve as repositories for the heritage of past civilisations, preserving artifacts and structures that offer insights into our shared history.

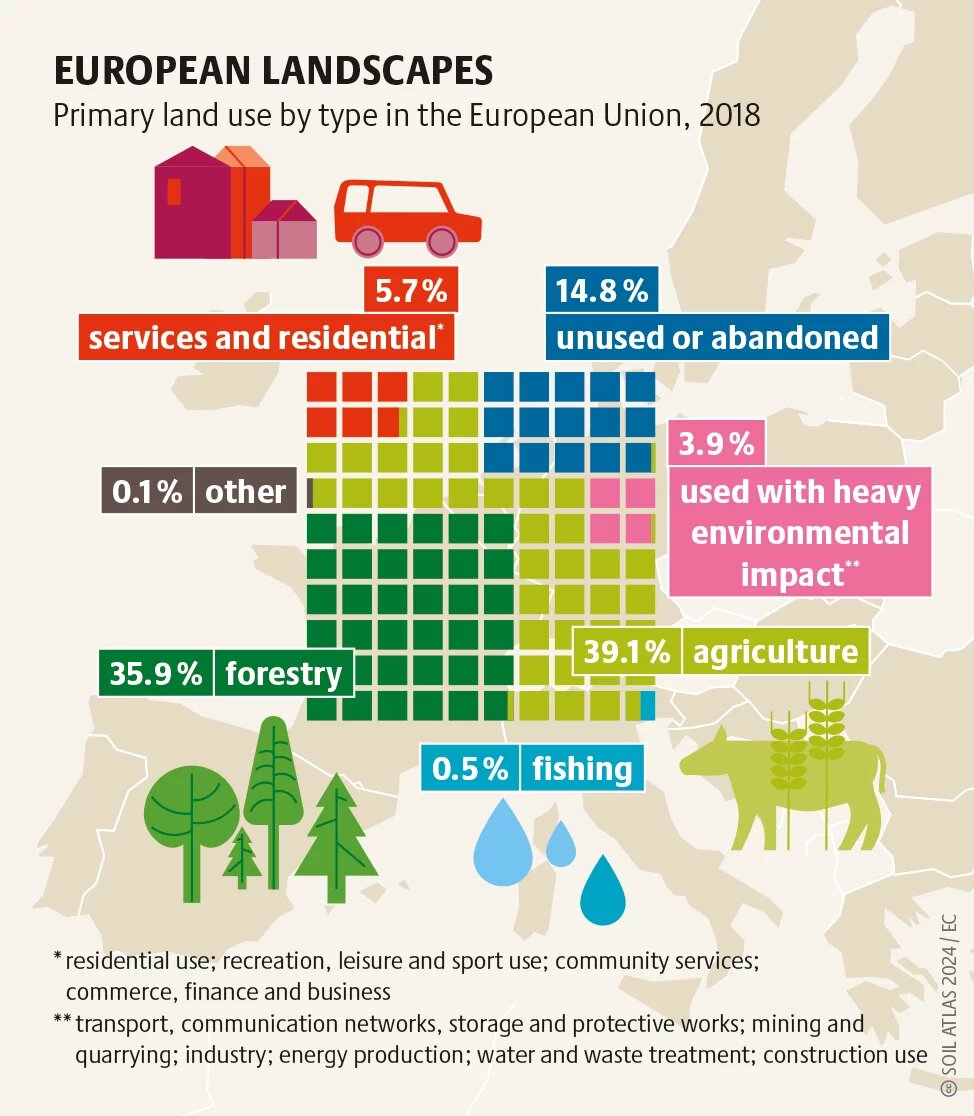

The overall health of soils relies on a balance in their physical, chemical, and biological properties. However, this balance can be disrupted in several ways. Misuse and overuse of fertilisers can render soils acidic, saline, or polluted. Intense ploughing damages the soil structure, contributes to the breakdown of organic matter and the release of carbon dioxide, and exposes the surface to erosion. These threats emphasise the need for sustainable soil management. Although some land use change and soil disturbance are necessary for food production, housing, and road construction, it is vital that we minimise negative impacts on soils. If we look after the soil, the soil will look after us.