Synthetic fertilisers harm the climate, but industrial farming relies heavily on them. Additionally, higher fertiliser prices have pushed up prices for food commodities. African countries, where food crises intersect with debt crises, are hit especially hard.

Between 2019 and 2022, synthetic fertiliser prices have tripled for several reasons. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia and China imposed export bans on fertilisers to certain regions, including Western Europe and India, to protect their domestic agriculture from higher fertiliser prices. The interruption of supply chains during the pandemic also led to temporary shortages in fertiliser supplies on the world market. Moreover, since mid-2021, Russia had restricted its exports outside the Eurasian economic area. Then, after Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine, battles around the Black Sea ports, which are important for the fertiliser trade, led to an abrupt stop in many trading activities. At the same time, the European fertiliser industry temporarily reduced its production by up to 70 percent due to rising prices of natural gas. Another key driver of fertiliser price increases were price spikes in the costs of fossil fuels such as natural gas, oil, and coal that are needed to produce nitrogen fertilisers.

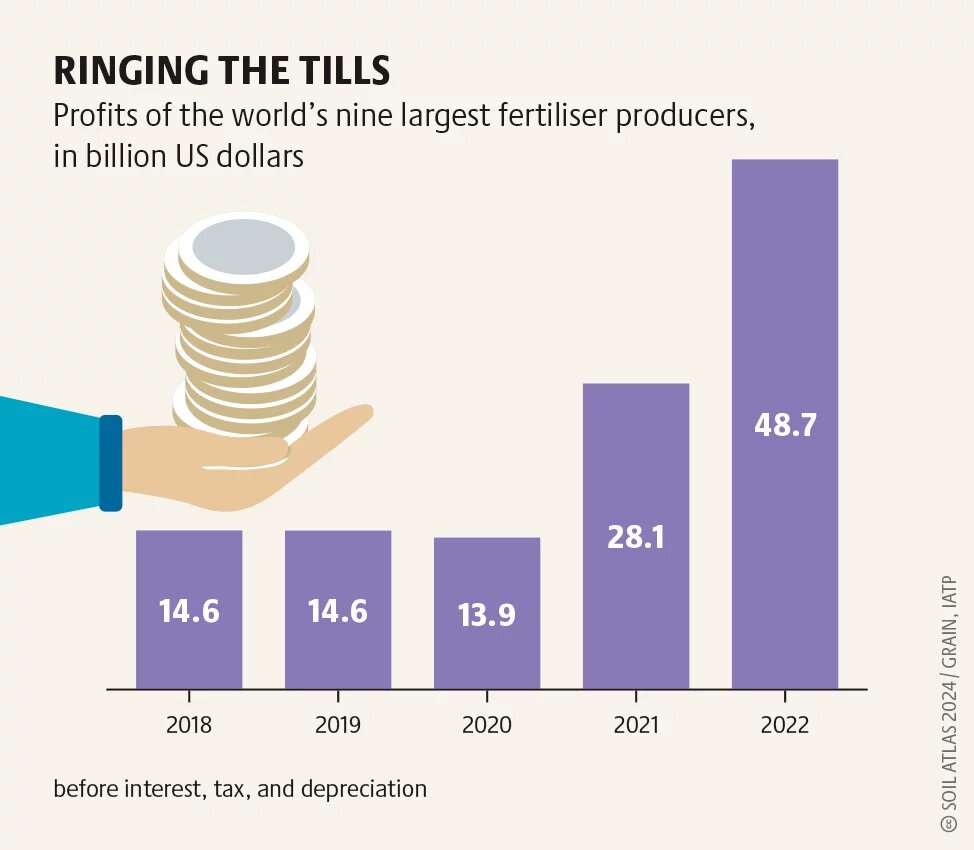

The effects of higher fertiliser prices can be seen at the supermarket checkout. In March 2022, the worldwide Food Price Index, which tracks the prices of food commodities, hit an all-time high. In the food crisis of 2007 and 2008, one study found that the doubling of fertiliser prices pushed up the price of food commodities such as grain, vegetable oils, and milk by an average of 44 percent. As a result, up to 100 million additional people worldwide suffered from hunger. But while price increases affect the global market and average consumers, the fertiliser industry benefited the most from alongside the oil and gas industry. In 2022, the nine largest fertiliser manufacturers registered an average profit margin of 36 percent. With decarbonisation plans and gas prices in the European Union (EU) still at a comparatively high level, some fertiliser companies are now moving their production to the United States, where natural gas is cheaper and government subsidies higher.

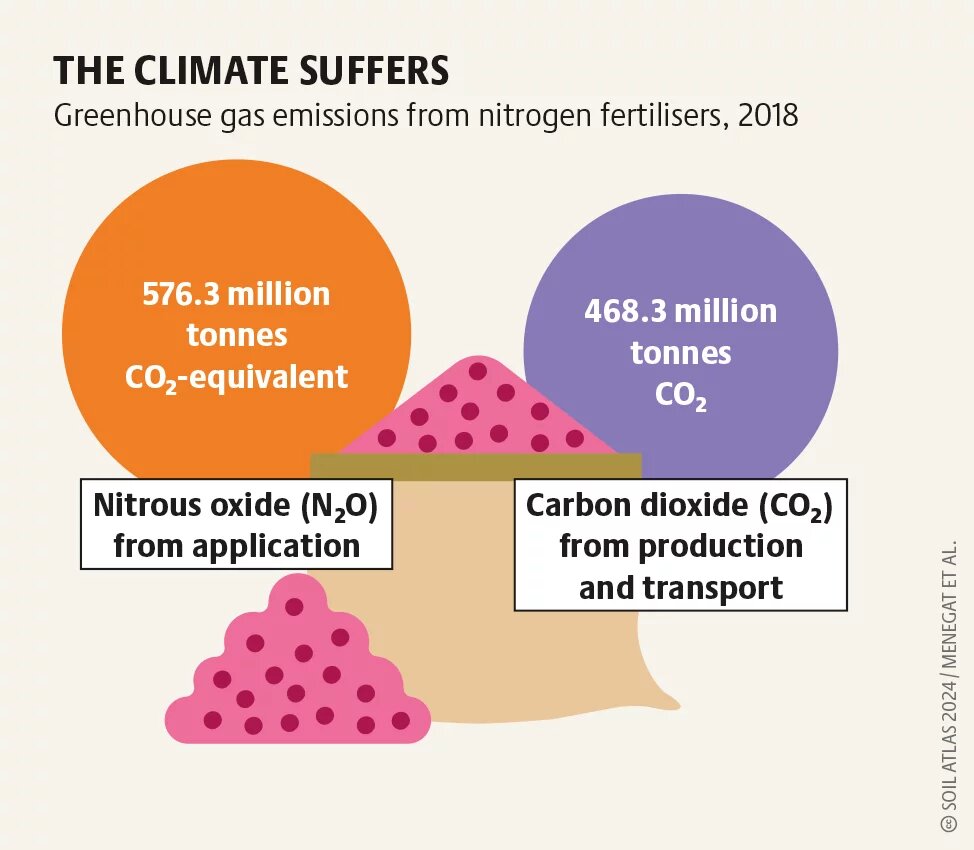

In addition to issues of price volatility, fertiliser production contributes to the climate crisis. The Haber-Bosch process, developed at the start of the 20th century, is central to the production of nitrogen fertilisers. Under temperatures of up to 500 degrees Celsius and high pressure, synthetic ammonia is produced from hydrogen and nitrogen. No other process to produce industrial chemicals emits more carbon dioxide (CO₂). The nitrogen fertiliser value chain alone is responsible for 2.1 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. About one-third of these emissions result from the production process. In addition, ammonia synthesis contributes between one and three percent to worldwide energy consumption every year. Due to its energy-intensive production, the price of nitrogen fertiliser is linked to the price of natural gas by around 90 percent.

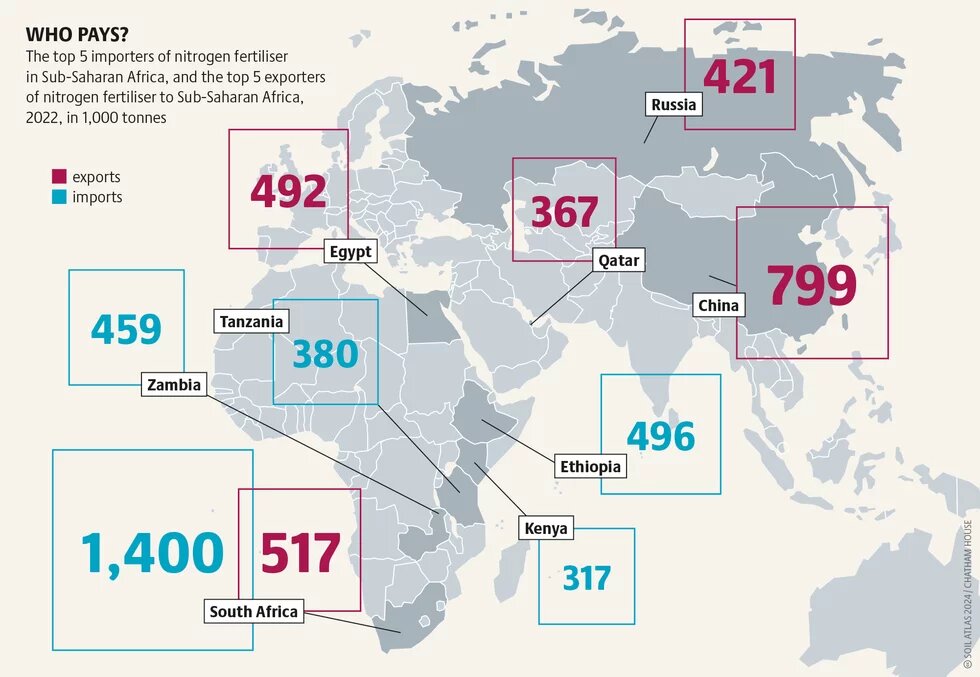

The uneven distribution of fertiliser production capacity means that the Global South depends on imports of synthetic fertilisers. In Sub-Saharan Africa, countries import an average of 80 percent of their fertiliser needs. That leaves them particularly exposed to price spikes. In Kenya, fertiliser prices rose over 150 percent from 2020 to 2022, increasing staple food prices. To partially alleviate the impact of these costs on farmers and the food industry, many African governments subsidise fertilisers. But such emergency subsidies are a heavy burden on the public wallet, demonstrating the risks and hidden costs of relying on synthetic fertilisers produced with fossil fuels. In Malawi, rising costs of fertiliser during the food crisis of 2007 and 2008 meant that fertiliser subsidies rose from 8 to 16 percent of the total national budget. Moreover, the percentage of low-income countries that are under debt distress, or threatened with bankruptcy, has almost tripled since 2013. According to the International Monetary Fund, around 20 countries, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan, face simultaneous debt and food crises.

There is a widespread assumption that high yields attained by applying synthetic fertilisers and pesticides lead to less hunger. But in fact, the connection is far from clear. This is illustrated by the case of Zambia: a country with the highest fertiliser use in all of Sub-Saharan Africa, heralding a five-year average of 65 kilograms per hectare. Zambia is among the top six African countries in terms of grain yields per hectare. However, the 2022 Global Hunger Index ranks Zambia at 110 out of 125 countries for which data is available. The large-scale industrial cultivation of maize and soybean in Zambia does not contribute to its food security.

The 2024 African Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan highlights that more fertiliser alone cannot solve the global food crisis. African heads of state stress improving soil health through holistic methods. The Action Plan promotes organic fertilisers and integrated approaches, but not the phasing out of conventional fossil fuel-based fertilisers. Major civil society organisations have welcomed this shift towards sustainability, but its impact hinges on implementation.