Substances that are proven to present a particularly high level of acute or chronic risk to health or the environment are commonly referred to as Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs). Far too rarely are these substances withdrawn from circulation – especially in the Global South they cause great harm.

To identify HHPs, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have outlined eight criteria: Pesticides are considered to be highly hazardous if they have an acute lethal effect, cause cancer or genetic defects, impair fertility, or harm unborn children. Likewise pesticides are classified as highly hazardous if they cause serious or irreversible damage to health or the environment under normal conditions of use or are listed in internationally binding conventions like the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, the Rotterdam Convention, or the Montreal protocol.

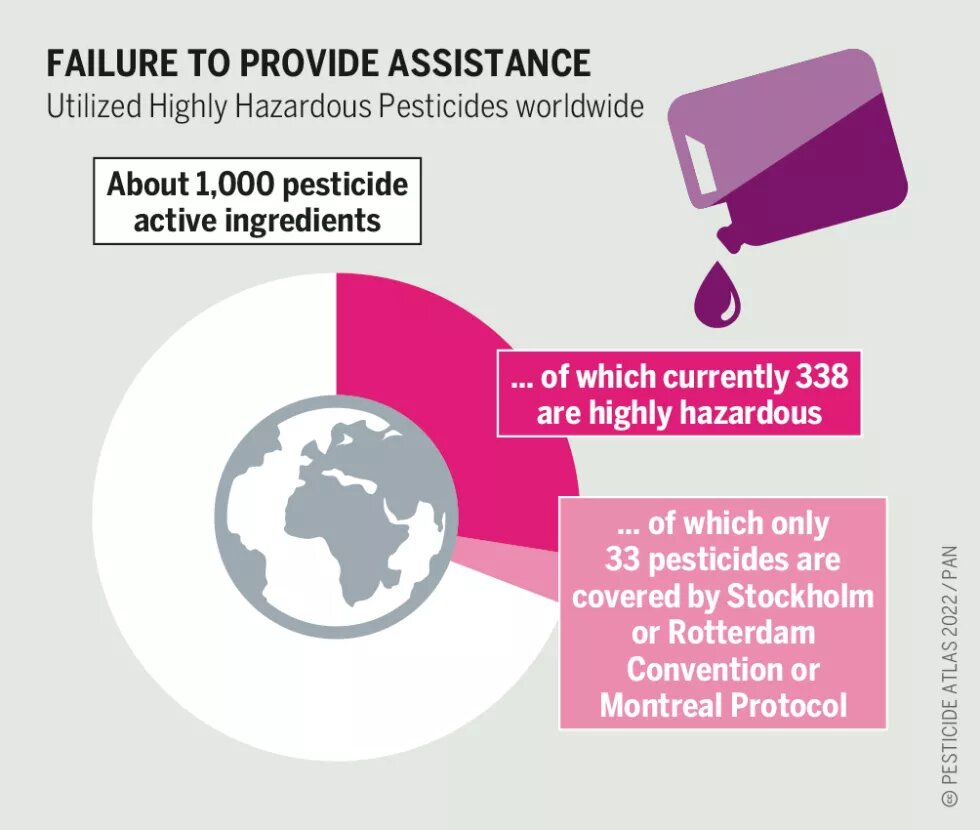

Although the FAO and WHO developed these criteria, they have not published an official list that includes all HHPs used worldwide yet. This makes it challenging for governments, agricultural extension agents, distributors, and appliers to identify and replace HHPs with less hazardous alternatives. The international Pesticide Action Network (PAN) has filled this gap and has published a periodically updated HHP list since 2009. It takes into account environmental criteria as well as additional human health impacts compared to WHO and FAO.

For years, studies have shown that HHPs cause great damage especially in countries in the Global South, and yet massive amounts of these specifically harmful pesticides are still applied to a vast extent there. In 2018, 40 percent of all pesticides used in Mali were highly hazardous, in Kenya 43 percent at the same time. In 2021, even 65 percent of all pesticides used in four states of Nigeria were highly hazardous. In Chile, one quarter of all 400 active ingredients registered were HHPs in 2019, and in Argentina as many as 126 out of a total of 433. The use of HHPs in agriculture is also widespread in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Investigations could show that between 2019 and 2021 more than 70 HHPs were used in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, and as many as 95 in Armenia. Even though the EU has banned many HHPs, some specifically dangerous pesticides remain in use, even though they should be substituted according to EU regulations.

In many countries, the system of pesticide regulation is inadequate. Capacity with regards to quality and use control, advisory services and monitoring of pesticides are often insufficient or even entirely lacking. Many of the workers applying the pesticides are also poorly trained or not trained at all: The lack of safety trainings frequently leaves them unaware of the health hazards involved in handling pesticides. A lack of information about hazardous substances and difficulties in accessing disposal centers for empty pesticide containers impedes the return process. In some countries, disposal centers do not even exist. And in many cases there is not even access to personal protective equipment or hot climate makes wearing such impossible which creates additional problems. This results in a high number of injuries and deaths: 95 percent of 385 million people who suffer from unintended pesticide poisoning each year live in the countries of the Global South. United Nations experts have considered HHPs a global human rights concern for a long time: Pesticides threaten among others the right to live in dignity, the right to bodily integrity, and the right to a healthy environment. Also, pesticides are often applied disregarding mitigation measures like buffer zones to protect surface waters, or specific spraying times to protect pollinators, and even though these measures are practically not feasible in many regions, the pesticides still remain on the market.

Despite their dangers, using HHPs seems normal these days – but it does not have to be. Many regional projects in both the South and the North have demonstrated that agroecological farming practices are a viable alternative. However, this transformation can only succeed if governments and the international community set appropriate priorities. It is particularly important to raise awareness of the risks of pesticides and to push for the development of non-chemical alternatives. Key elements include research funding, and the collection and dissemination of information on viable alternatives to HHPs, ranging from ecological and cultural management measures to biological control measures and as a last resort a restrictive use of biopesticides.

A progressive ban on HHPs was recommended by the FAO as early as 2006. Developing safer alternatives is the goal of the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM), which aims to reduce the usage of Highly Hazardous Pesticides. Nevertheless, there is still no globally binding legal framework that addresses pesticides in their full scope – from production to use to disposal, and with strict deadlines for phasing out HHPs.