There are good reasons to wish for a future with more heat pumps: less fossil gas in the heating sector and therefore less methane leakage and less CO2 and NOx emissions; lower costs for households; and more energy independence for nations. Most of this works best with powering the heat pumps with a bigger share of renewables. In Europe, heat pumps boomed until 2023 and then dipped to 2020 or 2021 levels in 2024. Starting points and paces of change in the heat pump market differ wildly. Let’s have a virtual trip to Sweden, France and Germany and find out why those timelines are so different.

The International Energy Agency calls heat pumps the ‘central technology’ for low-carbon heating. While geopolitical shocks and national decisions shape adoption patterns, for most consumers the decisive factor is the electricity to gas price ratio, a study by the German state-owned promotional bank KfW shows.

Heat pumps efficiently electrify heating, working like reverse refrigerators. A refrigerant absorbs ambient or geothermal energy, which is compressed and transferred indoors via a heat exchanger. Because they salvage thermal energy from the environment, modern heat pumps deliver three to four times more energy than the electric energy they consume, measured by the seasonal performance factor (SPF).

A heat pump with an SPF of 3 produces 3 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of heat per 1 kWh of electricity, while gas boilers convert 1 kWh of gas to almost 1 kWh of heat. Thus, if electricity costs are less than three times the gas price, heat pumps are more economical.

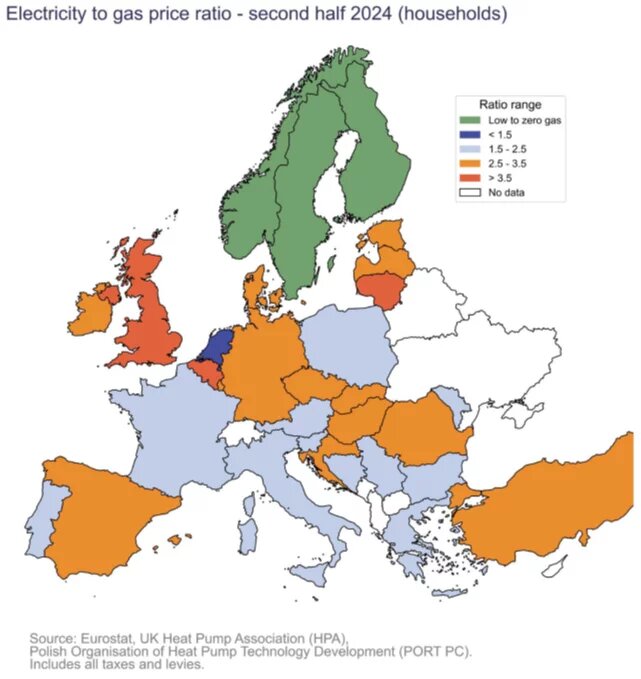

The electricity-to-gas price ratio varies widely across Europe, influenced by historic policy choices – from reactions to the 1970s oil crises to the gas price shocks after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The paths of Sweden, France and Germany illustrate how national structures, energy policies and markets shape this ratio.

Figure 1: Electricity to gas price ratio 2024 (Source: EHPA Market Report 2025)

Sweden: An early switch from oil, early research in heat pumps and a low share of gas in heating

- Electricity to gas price ratio (2024): 1.5

- Heat pump stock (2024): ca 50 per 100 households

- Heat pump sales (2024): ca 3 per 100 households – market share: 92.4%

The Nordics lead Europe in heat pump stock and sales. With no extensive gas grids, households historically relied on oil or electric resistive heating. That and the open architecture of many homes make air-to-air heat pumps especially attractive, with no need for extensive ducting and renovation. The Nordics show that heat pumps work very well in cold climates.

Sweden began adopting heat pumps in the 1990s, with rapid growth from the early 2000s. After the oil shocks of the 1970s, it decided to move away from oil. The Swedish Energy Agency promoted research, and in 2005, the government created a Commission for Oil Independence. Sweden is now one of the world’s top four heat pump exporters. Its large-scale adoption, combined with district heating reform and better building efficiency, makes it a European leader in decarbonizing heating.

Policy drivers

Sweden introduced a carbon tax in 1991 (€21 per ton of CO2), which has risen to €134 per ton of CO2 in 2025. Consumer costs for gas and oil are at the same level as electricity. Households can deduct installation costs for heat pumps but receive no direct purchase subsidies. Government tenders support R&D to increase efficiency and lower costs of heat pumps, while information campaigns and training of installers build consumer confidence.

France: Nuclear power provides 70 per cent of electricity, but fossil fuels dominate heating

- Electricity to gas price ratio (2024): ca 2.5

- Heat pump stock (2024): ca 20 per 100 households

- Heat pump sales (2024): ca 1.7 per 100 households – market share: 45%

With over four million installed units – mostly air-to-water – France has more heat pumps than any other European nation. In stock and sales of heat pumps, it leads the bigger industrial nations of the EU. Yet fossil fuels still dominate heating: in 2024, about 12 million households used gas boilers, and in 2022, roughly 3.5 million relied on oil. In 2020, 36 per cent of metropolitan homes were heated by network gas and 37 per cent by electricity, most of it inefficient resistive heating. Heat pump adoption began rising in the 2010s and accelerated after 2020.

Historical background

In response to the 1970s oil shock, France rapidly built nuclear plants. By the mid-1980s, nuclear supplied 70 per cent of electricity, creating oversupply during certain times. To use this capacity, the state and the state-owned electricity supplier EDF promoted electric heating and capped retail power prices. Fossil fuels were taxed more heavily, and since 2022, new oil boilers have been banned, with a plan to replace all oil boilers by 2028.

The MaPrimeRénov programme, introduced in 2020, offers grants for heat pumps, tiered based on income, household size and region. VAT on heat pumps has been lowered to 5 per cent from the regular 20 per cent. The new building code RE2020 encourages passive-house standards and heat pump use in new construction.

Germany: Expensive electricity and reluctant move away from gas

- Electricity to gas price ratio (2024): ca 3.25

- Heat pump stock (2024): 5.4 per 100 households

- Heat pump sales (2024): ca 0.6 per 100 households – market share: 27%

In my neighbourhood, with its 40-year-old single houses and gas heating all around, the change to low carbon heating moved in stages. People began using solar thermal hot water heating and solar photovoltaics (PV) about 25 years ago, but only on a part of their roofs. Now many equip their whole roofs with solar PV, put batteries in the basement and reconsider heat pumps. They also reconsider when renovating. Heat pump sales began rising after 2015 and surged after 2022 as gas prices soared following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2024, 77 per cent of new single homes installed heat pumps, while gas boilers fell to 5 per cent in new builds.

Historical pricing and policy

Germany’s response to the 1970s oil shocks was different. It introduced the ‘Kohlepfennig’ (‘coal penny’) – a levy on electricity to subsidize coal – keeping electricity expensive. Promoting energy savings through the imposition of higher prices became a centrepiece of German energy policy. Even today, about a third of the electricity price consists of taxes and surcharges, including 19 per cent VAT. As a result, Germany has Europe’s highest household electricity prices.

Gas was long considered a ‘bridge fuel’. Nuclear phase-out and industry interests delayed its reduction. The national emissions trading scheme (2021) added €55 per ton of CO2 by 2024. That and the dependency on Russian gas doubled retail gas prices after 2022.

Recent developments

The traffic light coalition of Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals in 2023 launched a tiered grant scheme covering up to 70 per cent of heat pump costs for low-income households. Yet a media backlash against the new heating law eroded public trust, portraying the shift as coercive. Consumers remain very sceptical after municipalities were tasked with a new local heat plan. By 2025, a new coalition led by Christian Democrats announced plans to slash or fundamentally alter the heating law again.

What now?

After record growth in 2022–2023, the European heat pump market slowed in 2024. Falling gas prices, high interest rates and policy uncertainty reduced sales – down 24 per cent in France and Sweden and 48 per cent in Germany, returning to 2020–2021 levels. Recovery began in 2025 and is expected to continue through 2026.

In 2027, the EU will launch the new Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS2), extending carbon pricing to heating fuels. This will raise gas prices across Europe. The German consumer organisation Verbraucherzentrale calculated that a typical household gas boiler in a single home could incur €9,500 in carbon costs for 20 years. The EU’s Social Climate Fund, financed by ETS2 revenues, could support heat pump adoption and socially buffer the cost for change.

Energy-independent housing also supports the trend. France’s RE2020 standard promotes nearly zero-energy or energy-positive homes, where efficient heating, rooftop PV and insulation complement each other. Rethinking district heating brings change at the communal level, like in Copenhagen or Stockholm, where it includes very large heat pumps and large reservoirs to store heat seasonally. This seasonal heat storage can balance seasonal differences in renewable energy production. Munich, Mannheim, Cologne and smaller cities in Germany that introduced communal heat planning have all followed that model as part of a strategy to become carbon neutral by 2045.

The views and opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.