Plastic waste, industrial effluent, chemicals: scarcely a single body of water is safe. They threaten ecosystems, biodiversity, and human health. The solution to the wave of pollutants? A circular economy that conserves resources.

Starting in the mid-19th century, the first modern sewerage systems were built in the rapidly growing metropolises of Europe and North America. Water was used to flush away street grime, human waste, and industrial discharge. But the idea that rivers would clean themselves soon proved to be an illusion: rivers and lakes became stinking, toxic cesspools.

Around 80 percent of all wastewater worldwide enters water bodies without undergoing treatment. An example of the consequences of industrial effluent is the Citarum River in Indonesia, which is regarded as the second most polluted river globally, after the Ganges in India. The industrial effluent from more than 2,000 factories on its banks makes it a life-threatening danger for those with no alternative water source. Studies point to 50,000 deaths every year.

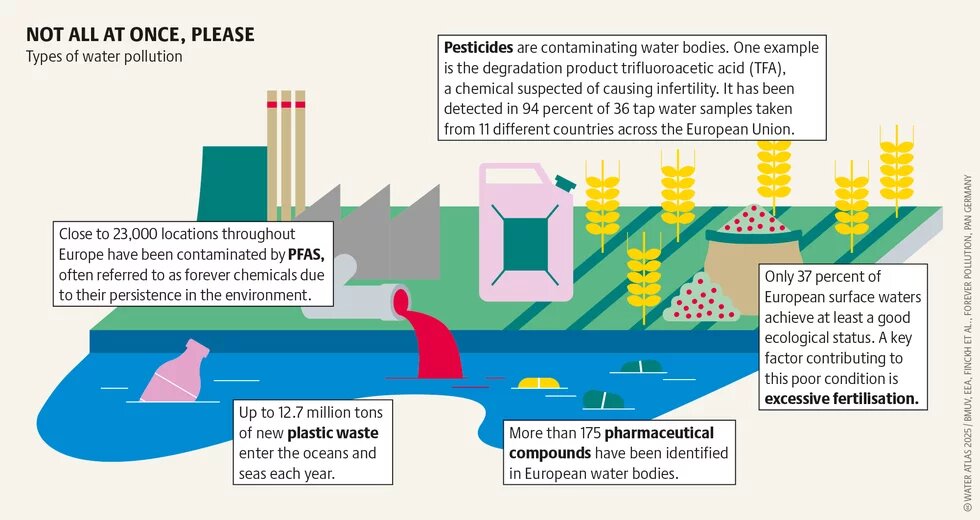

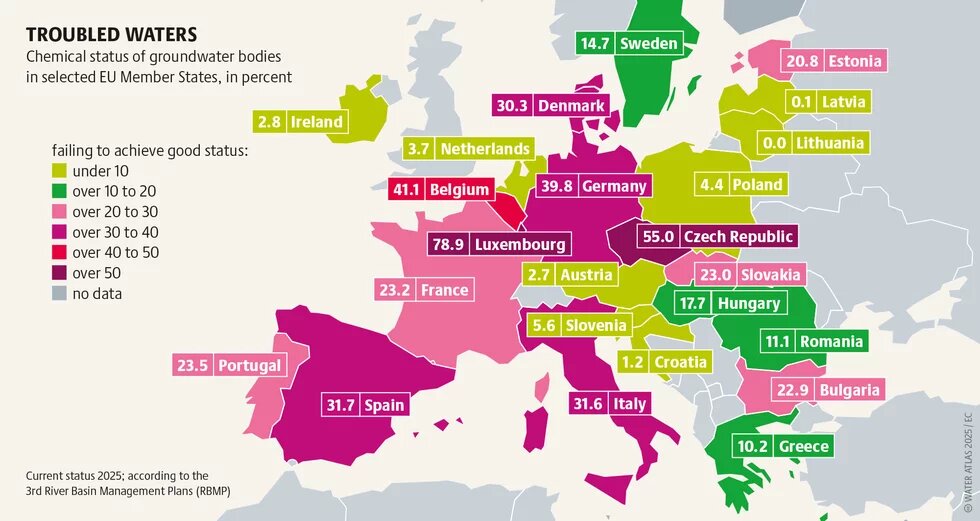

Today, synthetic fertiliser is a major cause of excessive algal growth, oxygen deficiency and fish die-offs in water bodies. In regions dominated by industrial agriculture, far too much fertiliser is released into the environment. Plants absorb only a fraction of the nutrients, while the remainder is washed into groundwater, rivers and ponds by rain and drainage ditches. In 2020, around 859,000 tonnes of nitrogen and 26,000 tonnes of phosphorus were released into the Baltic Sea. The European Union’s acceptable limit for nitrate is 50 milligrams per litre; according to the European Commission this value was exceeded at 14.1 percent of Europe’s groundwater measuring stations. This results in substantial economic costs. Among other impacts, contamination significantly increases water treatment costs. In Europe, the economic costs of nitrates and other reactive forms of nitrogen are thought to be as high as 320 billion euros per year.

Pesticides also pollute streams, rivers, lakes, the sea and groundwater reservoirs. They are used in agriculture to protect harvests from fungi, weeds and insects. Around 322,000 tonnes of pesticides were sold in the EU in 2022. From farmland and fields they run off or leach into water bodies, where they impair the water quality and harm fish and other aquatic life – and ultimately pose risks to human health. Many pesticides also contain PFAS (perfluorinated and polyfluorinated alkyl compounds), which are sometimes called forever chemicals because of their extraordinary persistence. In the European Union, the number of fruit and vegetable varieties containing residues of at least one PFAS pesticide has tripled in the last 10 years.

PFAS are highly persistent industrial chemicals used across numerous sectors, and they can cause enormous damage to the human body. They are also common in plastic waste, which releases additives such as plasti-cisers and breaks down into ever-smaller pieces known as microplastics. Even some fertilisers are now wrapped in layers of plastic in order to prolong their effect. Applying such pellets in this way causes plastic to accumulate in fields, from where it ends up in water. Marine animals are defenceless against plastic waste; they ingest it or become entangled in larger plastic debris. Wealthy industrialised nations export large quantities of plastic waste to the Global South, resulting in significant environmental and public health issues in those regions. Plastic pollution is a financial burden especially for low- or middle-income countries. Even though these countries consume only just over one-third of the plastic per person as wealthy industrial nations, the clean-up costs can be up to ten times higher.

Another problem is oil, which finds its way into the sea through shipping, tanker accidents, leaks in oil platforms, illegal disposal or industrial effluents. Globally, oil slicks cover 1.5 million square kilometres of ocean – an area twice the size of Turkey. The oil suffocates marine life, poisons food webs, and causes long-term ecological damage.

To treat wastewater more efficiently, the European Union plans to upgrade larger sewage treatment plants with an additional fourth treatment stage. But such an upgrade is costly and is therefore unlikely to be adopted globally. And even a fourth purification stage cannot completely filter out problematic chemicals such as PFAS.

It is therefore crucial to act proactively, preventing pollution before it occurs. Clean production methods offer the most effective solution for protecting the valuable resource of water as this avoids pollution right from the start. If water is recirculated and used several times during the production process, this reduces both the amount of water consumed and the amount of contaminated wastewater. Some Mediterranean members of the European Union already use treated wastewater in agriculture.

In some cases, it is possible to avoid using water altogether, for example by installing dry toilets. These are increasingly common in festivals and could help save water in everyday life. Since dry toilets do not require water, they eliminate the need for complex chemical and biological wastewater treatment. Human faeces in fact contain valuable nutrients that can be hygienically processed to reduce the use of synthetic fertilisers and to improve soil quality.

However, isolated solutions alone are not sufficient. Real improvements in water protection require both technical innovations and especially political regulation and social change. Fundamental changes in agriculture, industry, and sanitation systems are needed to achieve real improvements in water protection.