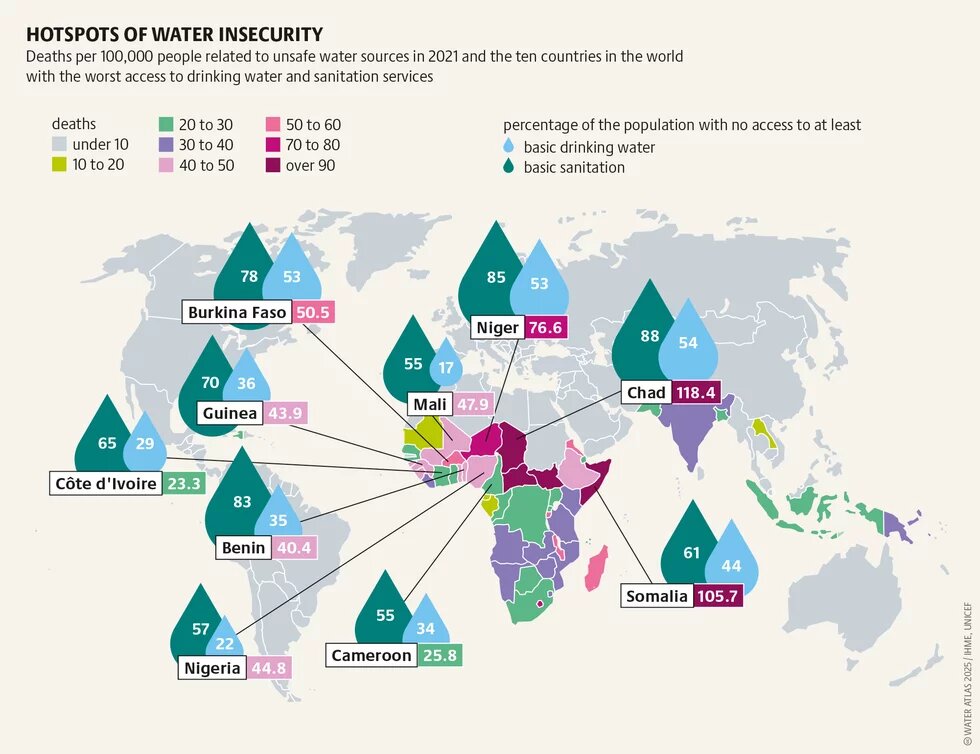

Over a quarter of the world’s population has no safe access to drinking water. To improve this situation, the United Nations has declared water a human right: it must be safe to drink and accessible to all. Decisive political action is required to prevent such well-intentioned efforts from faltering.

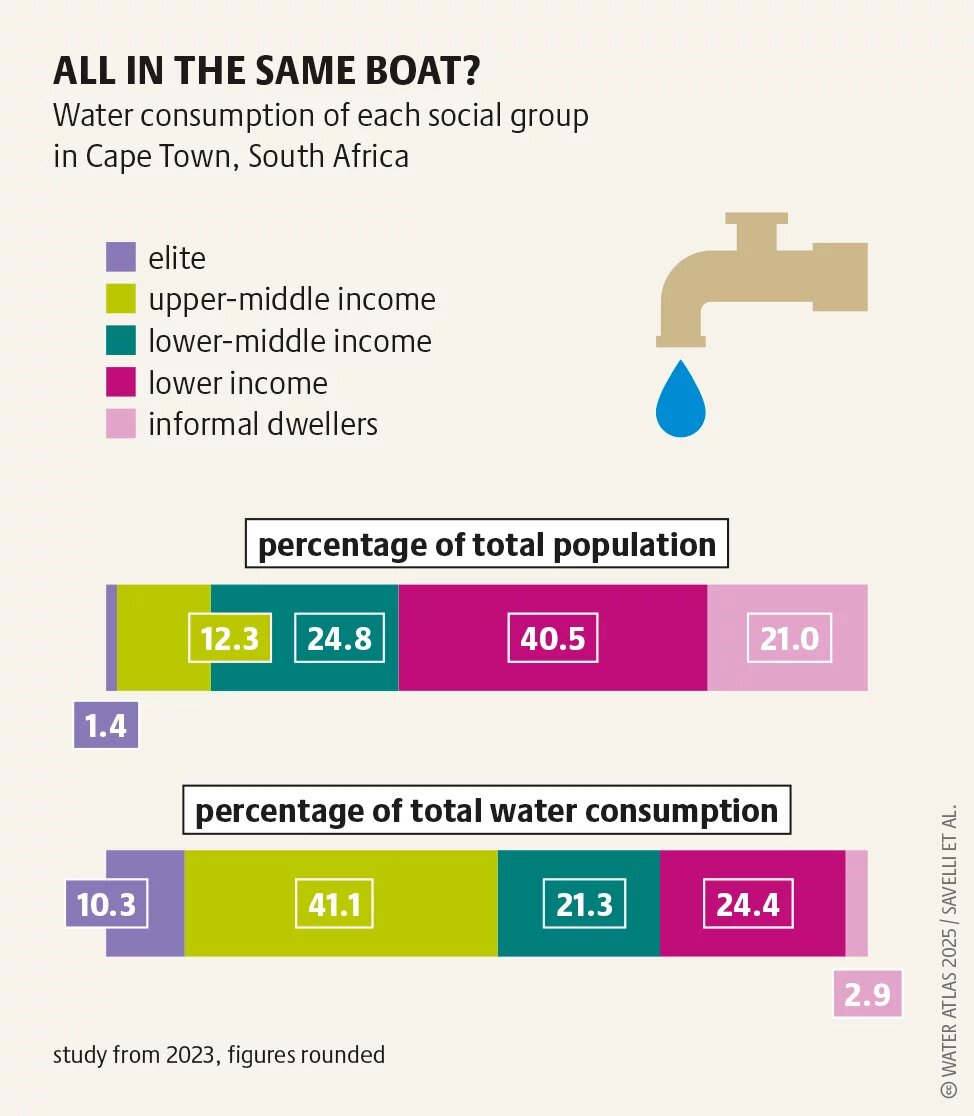

The human right to water does not just mean having enough water to drink. It also means having enough water for cooking, cleaning, washing, and personal hygiene. One person needs at least 50 to 100 litres per day to cover all these needs. The right to water is also closely related to the right to basic sanitation. For many people that remains an unattainable reality: some 3.5 billion people still have no functioning toilet in their home. This is often not due to a lack of water, but to its uneven distribution and poverty.

The rights to water and sanitation have increasingly been recognised in recent decades under international law. These rights are derived from Articles 11 and 12 of the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). Article 11 addresses the right to an adequate standard of living, and Article 12 recognises the right of all to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The Human Rights Council and the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) have recognised both these rights; while their decisions are not binding, they carry significant political weight. To help individuals to enforce guaranteed rights, the European Union (EU) has revised its Drinking Water Directive: a right to water has now been explicitly established at the EU level. This is intended to support vulnerable groups, especially homeless people, who often have limited access to toilets and clean water. One example is Germany, where the official number of homeless people in 2022 was around 262,600 – a figure that includes both those without their own place of residence who are staying with friends or in temporary accommodation, and people who live permanently on the streets. The actual number of homeless people in Germany is likely to be higher. One survey found that 20 percent of the homeless had no access to tap water – and for those without any accommodation, it was as high as 37 percent. Providing drinking water in public places would at least be a first step to alleviating this problem. One-third of the survey respondents also stated that they had access to water for drinking but not for washing.

The climate crisis is making it more difficult to ensure a right to water. A recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) clearly shows this: between 2002 and 2021, 1.6 billion people were affected by flooding, while 1.4 billion people suffered from droughts. In the EU, groundwater levels have been declining for years. Annually, approximately 20 percent of the land area and 30 percent of the population face water stress, with droughts causing economic losses of up to nine billion euros per year, in addition to immeasurable damage to ecosystems. Southern Europe is particularly affected. Around 14 percent of the groundwater monitoring stations in the EU report nitrate concentrations exceeding the maximum permissible level of 50 milligrams per litre. This nitrogen compound can harm the health of babies; it enters the groundwater in the form of agricultural fertilisers.

The right to water therefore requires more than guaranteed access to water: its quality must also be protected in the long term. A large part of the world’s population still has insufficient access to clean water. At least 3 billion people are reliant on water that is not monitored for quality. More than 2 billion people are exposed to drinking water that may be contaminated with pathogens. That is why water should have a much higher priority on the international agenda. The UN Water Conferences in 2026 and 2028 present an opportunity to initiate a binding global agreement to protect water resources.

The textile industry is responsible for around 20 percent of the global water pollution. Textiles for the global market are often produced in regions where water is already scarce. One example is the extremely water-intensive production of cotton in India. There, it takes 23,000 litres of water to produce just one kilogram of cotton. The European Union’s new Supply Chain Law, the Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence, will require European companies above a certain size to identify and minimise risks such as excessive use of water at the production site. This may force companies to invest in infrastructure to treat water, or to require their suppliers to use more efficient irrigation methods. The law came into force in 2024. It remains to be seen whether it can contribute to strengthening human rights and environmental standards along the value chain.

How new legal approaches can lead to better protection for water can be seen in Panama. In autumn 2023, the country saw the largest protests in decades. Tens of thousands of people demonstrated with strikes and blockades in favour of shutting down the Cobre Panamá, the biggest copper mine in Central America. The protests were boosted by the fact that Panama had shortly before recognised Nature as an independent legal entity – one of the first countries in the world to do so. Nature now enjoys similar rights enshrined in law as humans and legal entities such as firms. After the protests broke out, the Supreme Court of Panama referred to this when ordering the mine to be closed. The Court concluded that the continued operation of the mine would violate the Constitution because it threatened the rainforest and thereby the region’s water sources.