The climate crisis is disrupting the balance of the global water cycle. While rain floods entire regions, others suffer from severe drought. Where water becomes either a threat or a scarcity, the basis of life begins to falter. All the more crucial are solutions like restored wetlands and climate-resilient building in sponge cities, practices that can retain, manage – and safeguard – water and lives.

Scientific research shows that global warming increases the likelihood and intensity of heavy rainfall. Warmer air holds more moisture —approximately 7 percent more for every degree Celsius of warming—which results in more extreme downpours. This leads to flash floods that overwhelm drainage systems, damage homes and infrastructure, and disrupt lives. Such events have become more commonplace. For instance, recent flash floods in Spain 2024 and Texas in 2025 have caused widespread destruction and resulted in numerous fatalities. In July 2021, the catastrophic flooding in Western Europe was attributed to human-caused climate change, which had increased the likelihood of such heavy rainfall up to ninefold. Events like these are particularly devastating to communities already struggling with infrastructure that cannot handle sudden heavy water flow.

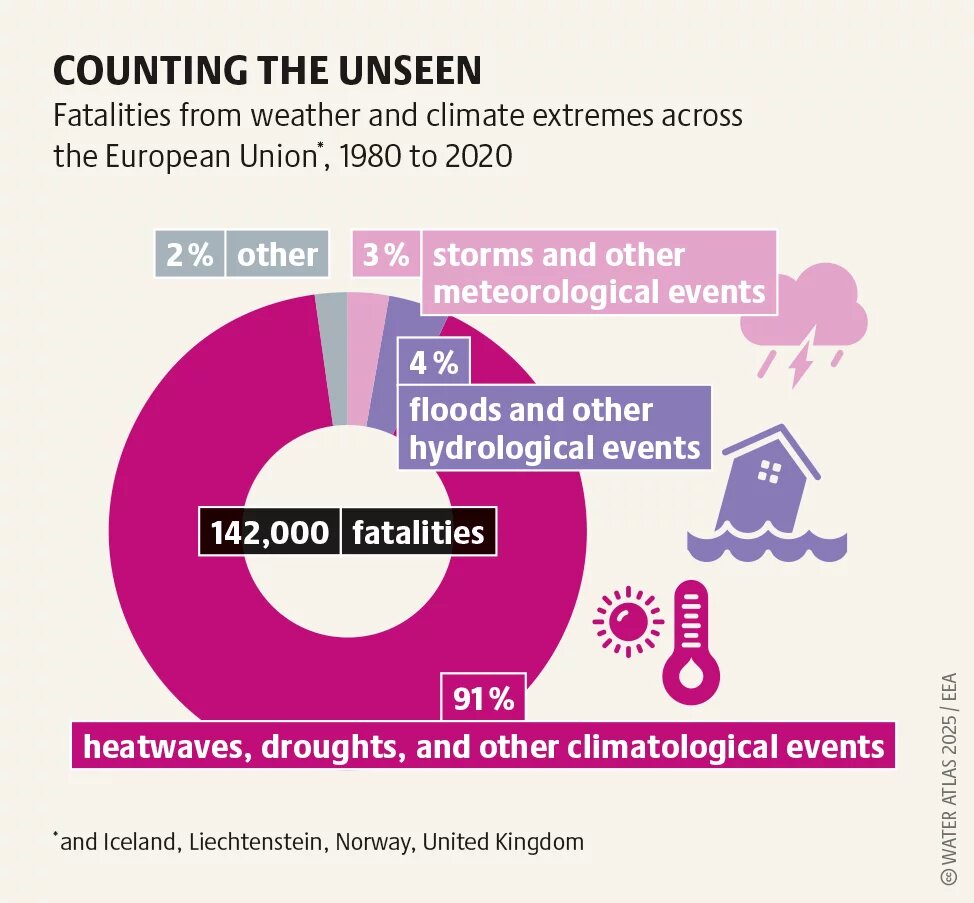

At the same time, other regions face the extreme opposite. Droughts are lasting longer and becoming more severe, especially in regions such as Africa, where rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns are depleting water supplies and undermining agriculture. Prolonged dry periods not only reduce crop yields but also threaten livelihoods, increase the cost of living, and strain social and public health systems. In Kenya, for example, millions have been affected by ongoing water scarcity. In Sub-Saharan Africa, safe drinking water remains out of reach for the majority of the population.

What makes the current moment especially concerning is how these climate-driven events increasingly interact. For example, a drought-stricken landscape heavily influenced by prolonged droughts often loses its capacity to absorb heavy rainfall: When rain finally arrives, water runs off swiftly, triggering flash floods and landslides. These cascading and compounding events can rapidly overwhelm already fragile systems, creating a feedback loop of climate-induced extremes. In 2024, prolonged droughts in Madagascar were followed by a powerful tropical cyclone, resulting in widespread flooding and leaving approximately 220,000 people in urgent need of humanitarian support, including around 22,000 who were displaced from their homes. These compounding events led to crop failure, food shortages, displacement, and a worsening humanitarian crisis, highlighting Madagascar's vulnerability to climate extremes.

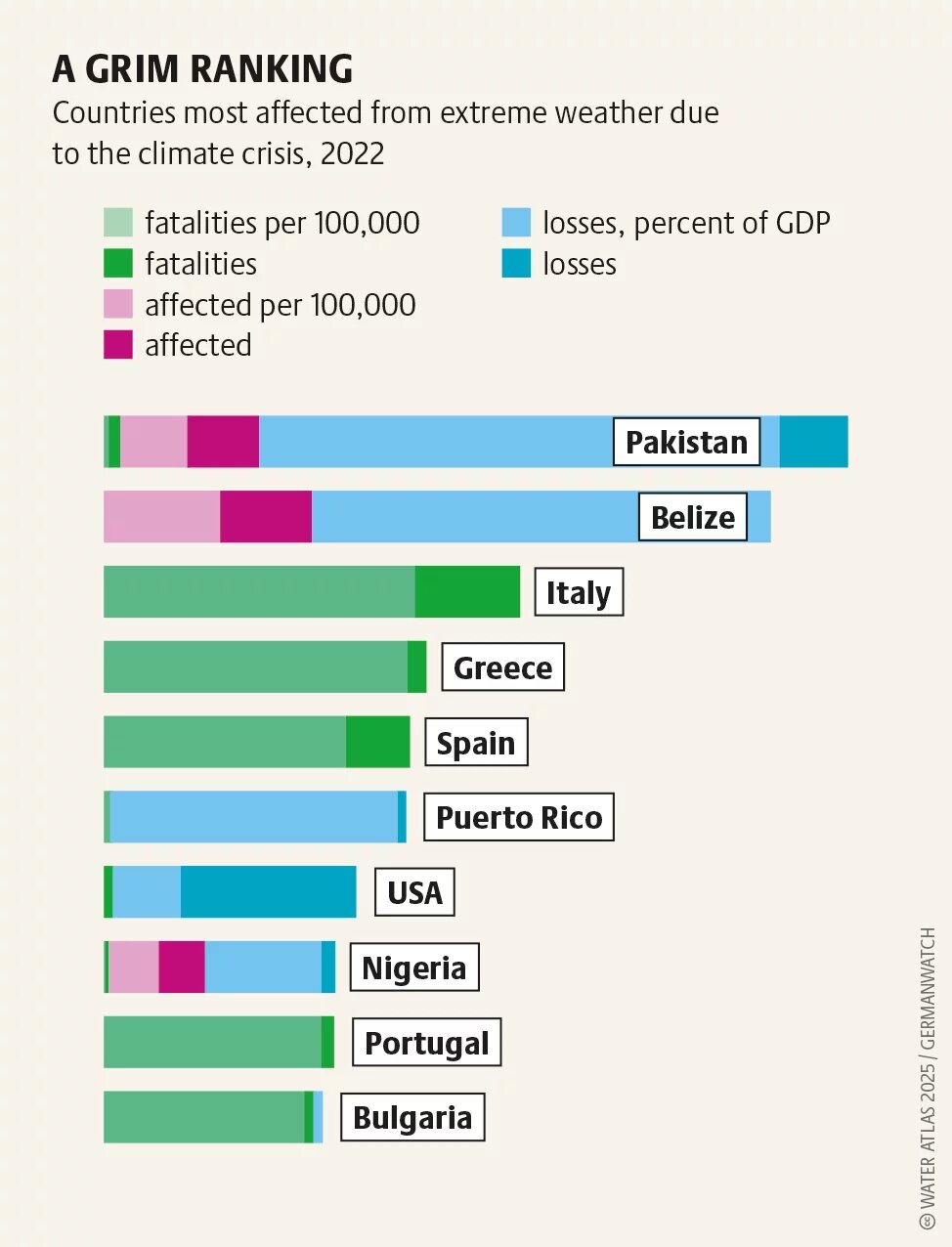

The climate crisis with its extreme weather events is also a crisis of inequality. Vulnerable groups such as low-income communities, women, and Indigenous populations often face heightened risks due to poor water governance and lack of access to resources, leading to social unrest and potential conflicts over dwindling water supplies. Agriculture, which accounts for about 70 percent of global freshwater usage, is under pressure as demand grows with population increases. Water scarcity thus threatens food security and livelihoods, particularly in regions dependent on climate-sensitive agricultural practices.

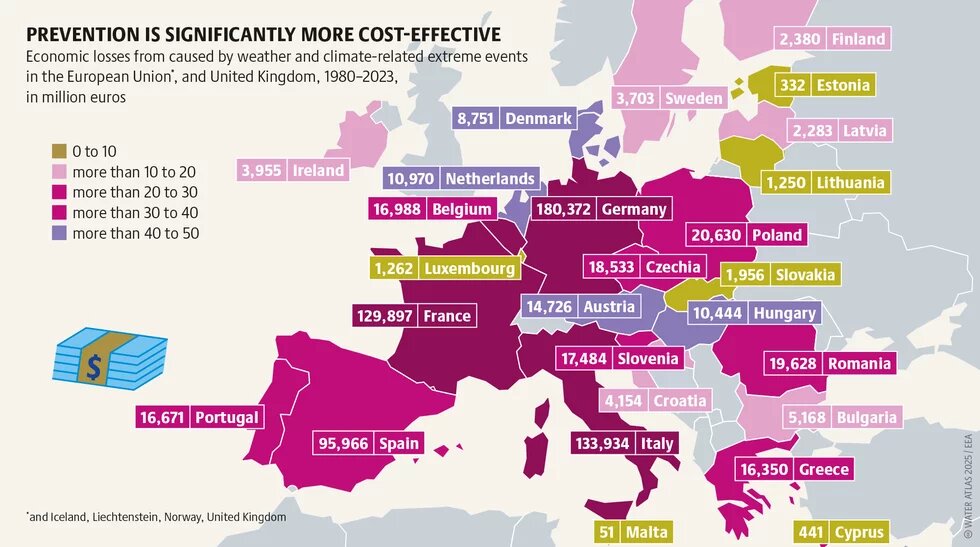

Tackling climate-related water challenges takes bold and coordinated action across all levels of society. Cities and regions need practical, forward-looking solutions that protect people and ecosystems from increasingly extreme weather. First of all, effective early warning systems are essential for protecting communities from the impacts of flooding. And urban planning, building regulations, and water management all play a vital role in protection. Updating building codes can make structures more resilient—for example, by requiring flood-proof foundations or materials that reflect heat instead of storing it. The concept of the sponge city offers a powerful approach: it transforms urban areas into landscapes that soak up rainwater like a sponge, filter it naturally, and release it slowly when needed.

To make this work, cities must replace concrete with permeable surfaces that allow water to seep into the ground. Green spaces help refill groundwater and lower the risk of flooding. Parks are essential, but so are green roofs and planted walls. Depending on the design, green roofs can retain up to 90 percent of rainwater. They also cool buildings naturally—on hot summer days, a roof with 10 centimetres of greenery can keep indoor temperatures up to 8 degrees Celsius lower than a bare, sun-heated flat roof.

The more green space a city has, the better it can handle heavy rains and rising heat. But resilience doesn’t stop at city limits. Restoring wetlands and protecting watersheds creates natural buffer zones that absorb floods and hold water during droughts. Climate-smart planning must bring these elements together so that cities and landscapes are not just protected but prepared.