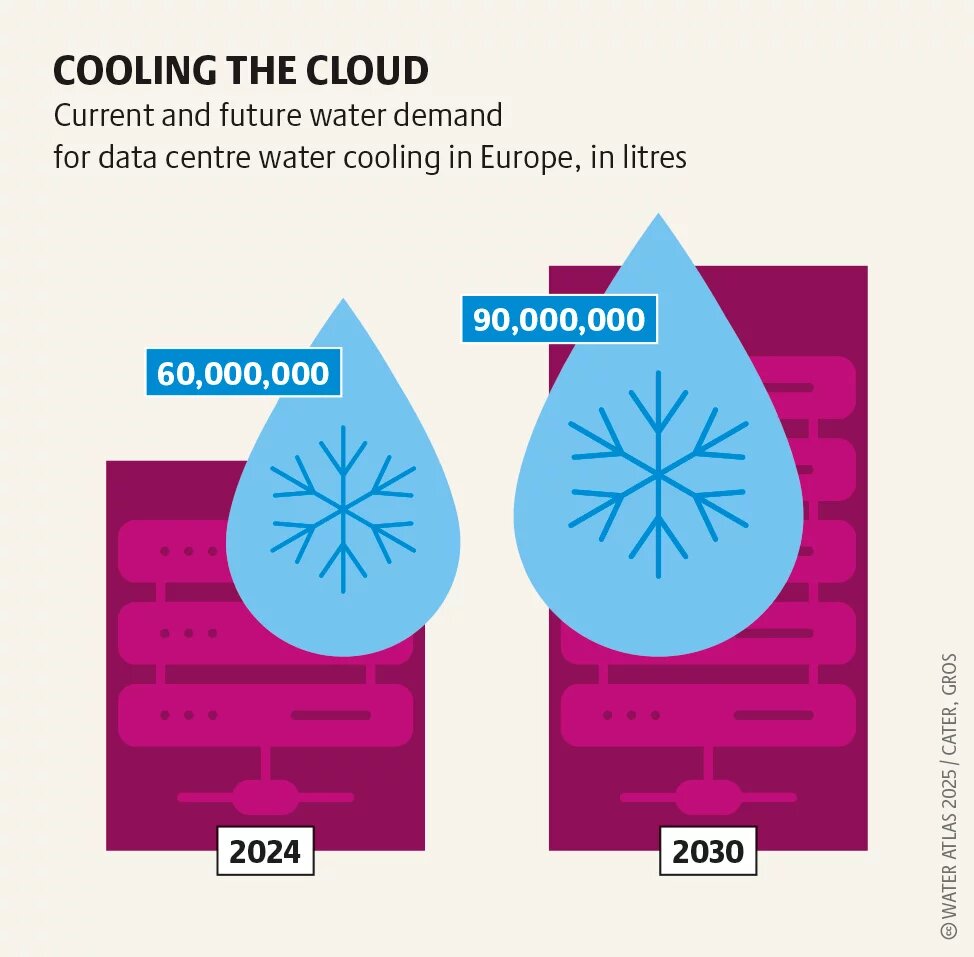

Digitalisation clearly enables new forms of mobility, living, and working. However, the rising energy consumption and water needs for artificial intelligence and other computing services pose ecological and social challenges.

Crunching data requires physical infrastructure: equipment such as laptops and mobile phones, adaptors and chargers, sensors, transmission networks – and above all, data centres. These centres are where most of the world’s data is stored, managed, and very much distributed. While the public has become increasingly aware of the carbon footprint as an indicator of the climate impact of digitalisation, the digital water footprint has been largely overlooked – despite the fact that data centres require large amounts of water to operate.

This water footprint actually consists of three main components. First is the water needed to produce the equipment itself; second is the water used to generate electricity to run the digital infrastructure continuously; and third is the water needed to cool the data centres effectively to keep the hardware at an optimal operating temperature. Research show, an average data centre in the United States needs more than a million litres of water a day – as much as three average-sized hospitals combined.

Data centres have to be kept cool to prolong the lifespan of the hardware. In one commonly used method, the water temperature is first lowered in a central cooling tower. The water then circulates through cooling coils that absorb heat from the air in the data centre and then release it outside via the cooling tower. A study by the Chilean water authority found that for cooling processes alone, a data centre requires up to 169 litres of water every second.

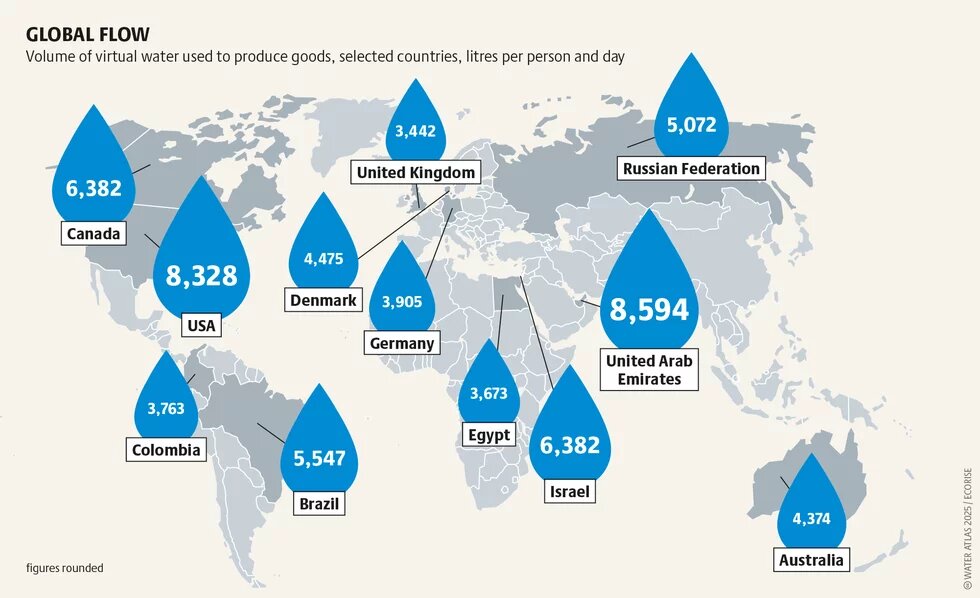

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems such as the chatbot ChatGPT have recently spread widely. These are algorithmic systems that make decisions not through traditional programming but via machine learning. They are trained on huge pools of data. Because they need a great deal of computing capacity, they are also responsible for rising water consumption in the data centres. While 20 Google searches use 10 millilitres of water, ChatGPT guzzles half a litre to answer 20 to 50 questions. When training the ChatGPT model GPT-3, for example, 700,000 litres of clean fresh water were evaporated in Microsoft’s research centres in the United States. The rising water consumption for artificial intelligence is also reflected in the fact that tech companies are drawing more and more water from the drinking water network: in 2022, Google used 20 percent more water than in the previous year; Microsoft used 34 percent more. By 2027, artificial intelligence worldwide is expected to consume up to six times more water as Denmark does. Cryptocurrencies also have a massive water footprint: the water consumed by a single bitcoin transaction would fill an entire swimming pool.

Many regions have already seen protests against the construction of data centres – especially in those areas that are already severely affected by water shortages. Uruguay is an example. Low rainfall and extreme heat in 2023 meant that the country’s most important reservoirs dried up. The authorities were forced to take water from the Rio de la Plata estuary, where seawater and freshwater mix, giving the tap water a salty taste. The protests focused on the planned establishment of a Google data centre, which was feared to worsen the water shortage. The demonstrators accused the government of prioritising water supplies for multinational concerns at the expense of the local population. This conflict shows that the ecological consequences of AI are closely linked to issues of distributive justice. In the meantime, the authorities have approved the establishment of the data centre – though with just one-third of the originally planned capacity and a comparatively water-saving air cooling system.

Although companies in the Global North in particular profit from technologies such as artificial intelligence, the ecological and social costs are borne mainly in the Global South. The public and scientific debate on how this can be changed is still in its infancy. In 2024, the European Union passed the so-called AI Act. This is the world’s first law to regulate artificial intelligence and obliges the documentation of the energy consumption and computing resources needed to train artificial intelligence models. But it does not require a similar documentation for water consumption because it regulates only the artificial intelligence products and not the technical infrastructure needed to run them. The European Union’s Energy Efficiency Directive does at least have reporting requirements for water use by data centres, which improves the transparency at least for data centres in Europe. Tackling the problem worldwide will require much greater investments in measures to reduce water requirements – such as alternative cooling systems or finding ways to use rainwater or seawater.

Only through global cooperation, stricter regulations, and a shift toward sustainable digital infrastructures can the environmental burden of digitalisation and AI be equitably addressed and long-term resilience ensured.