Water is vital for life on Earth. But overuse, pollution, and the climate crisis are endangering global water reserves, with far-reaching consequences for ecosystems and humans. To overcome crises, we must manage water sustainably.

More than 70 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered in water. But that was not always the case. When it was first formed, the Earth was a huge molten ball of fire. According to the most widely accepted theory, it acquired most of its water later from a bombardment of comets and asteroids about 4 billion years ago. These celestial bodies from distant, cooler parts of the solar system consisted largely of ice, which immediately vaporised in the enormous heat of the atmosphere. As temperatures gradually cooled over time, the water condensed and fell to the ground as a torrential downpour lasting thousands of years. The water flooded the surface, and the depths of the primordial ocean would later become the birthplace of life.

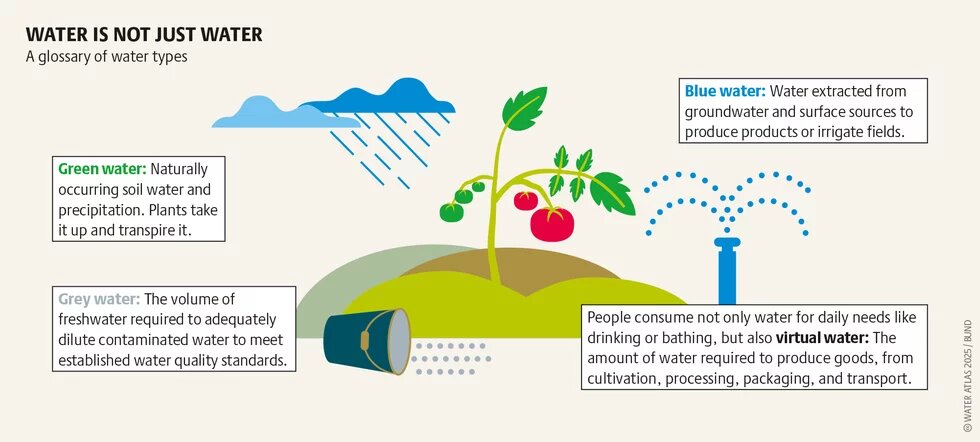

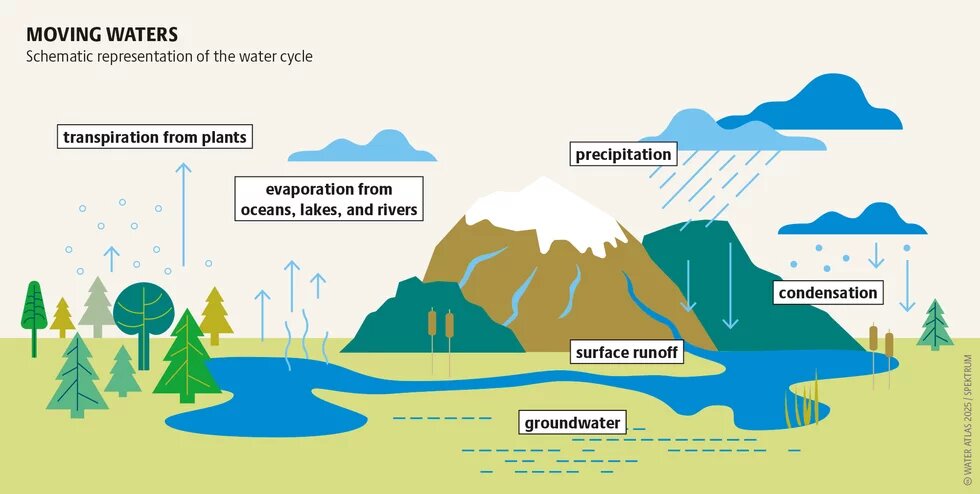

Today, 97.1 percent of the Earth’s water is in the form of salt water, mainly in the oceans. The rest is fresh water, and of that, 99.7 is tied up in ice caps or deep beneath the ground. The remaining 0.3 percent of fresh water – around 120,000 cubic kilometres – is in constant circulation between land and sea: above and below the surface, and in solid, liquid or vapour form. This creates a perfect cycle, for the same amount that is carried by the atmosphere onto the land eventually flows back into the sea. The complex patterns of atmospheric circulation are the main reason that freshwater is very unevenly distributed on the land in terms of both space and time. Less fresh water is found in the subtropics and during dry periods, while availability is greater in the tropics.

Human interventions are causing profound changes in the water cycle. In many parts of the world, water reserves are being overexploited or polluted. Ecosystems are suffering as a result, as are agriculture, industry, and households. Maintaining a reliable water supply for all is becoming increasingly difficult. Examples of dramatic developments relating to water abound. In Pakistan, northern India, and parts of the USA, groundwater levels have fallen drastically as a result of overexploitation. Glaciers are melting in almost all the world’s mountain ranges due to global warming. The consequences are dire for ecosystems and communities downstream, as they are affected by the fluctuating supply of river and meltwater. The biodiversity in and around water bodies is declining so rapidly that one-quarter of all known freshwater fish species are already threatened with extinction. Urban centres such as Mexico City, Beijing, and Cape Town are suffering from water shortages; 2.2 billion people lack regular access to clean drinking water.

The causes are as many and varied as the problems themselves. For example, river straightening and the sealing of the ground surface increase the extent of flooding. River diversions and dams harm or destroy aquatic ecosystems; spreading pollutants on the soil or into water bodies jeopardises the quality of drinking water. Using too much water for irrigation leads to shortages. The climate crisis causes more frequent and more severe weather extremes such as droughts and floods everywhere.

In order to protect aquatic ecosystems, it is important not to consume all available water. The planetary boundary for freshwater change plays a crucial role here. This is a kind of warning line that shows to what extent nature can cope without being seriously harmed. If water is consumed beyond the planetary boundary, the planet’s resilience to other environmental changes, such as the climate crisis, and the loss of ecosystems and their biodiversity, is weakened. According to recent calculations, the freshwater planetary boundary was breached decades ago. Up to 18 percent of the Earth’s ice-free surface has either unnaturally low or unnaturally high, water levels in rivers and soils. That is significantly higher than in pre-industrial times.

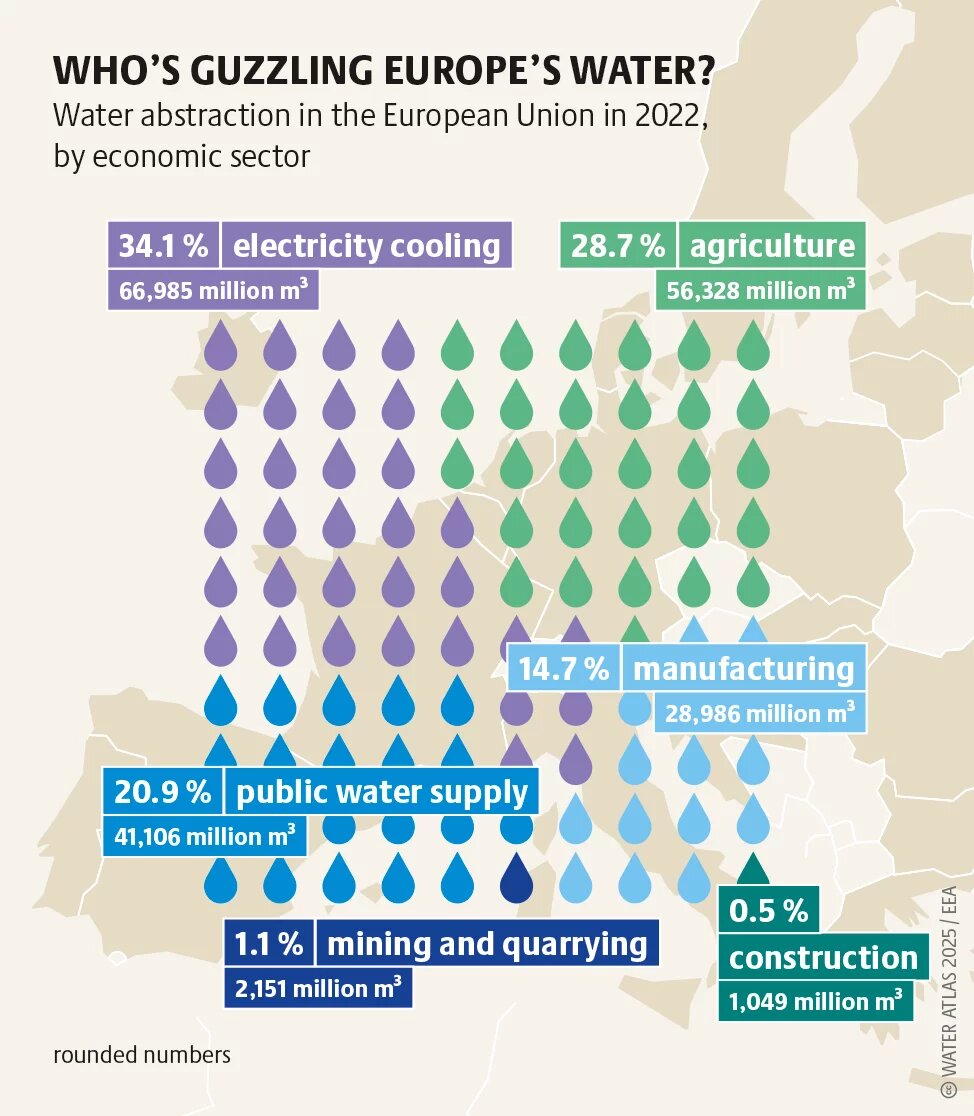

In the past, it was often assumed that water resources were stable and new reserves could always be tapped. In view of the climate crisis, such a cornucopia approach seems increasingly questionable. Policymakers must therefore increasingly focus on reducing water use and ensuring that water bodies are used more responsibly. A wide range of options are available to industry, and especially to agriculture. These range from collecting rainwater during wet periods, adopting tillage methods that reduce evaporation, and exporting water-intensive goods from water-rich to water-stressed countries.