Water is becoming scarcer in Colombia, and pollution is rising. Community water management offers a solution: it allows communities to take control of their water, make decisions collectively, and prioritise sustainability and equity. Could this democratic alternative be a chance to manage the world’s water challenges?

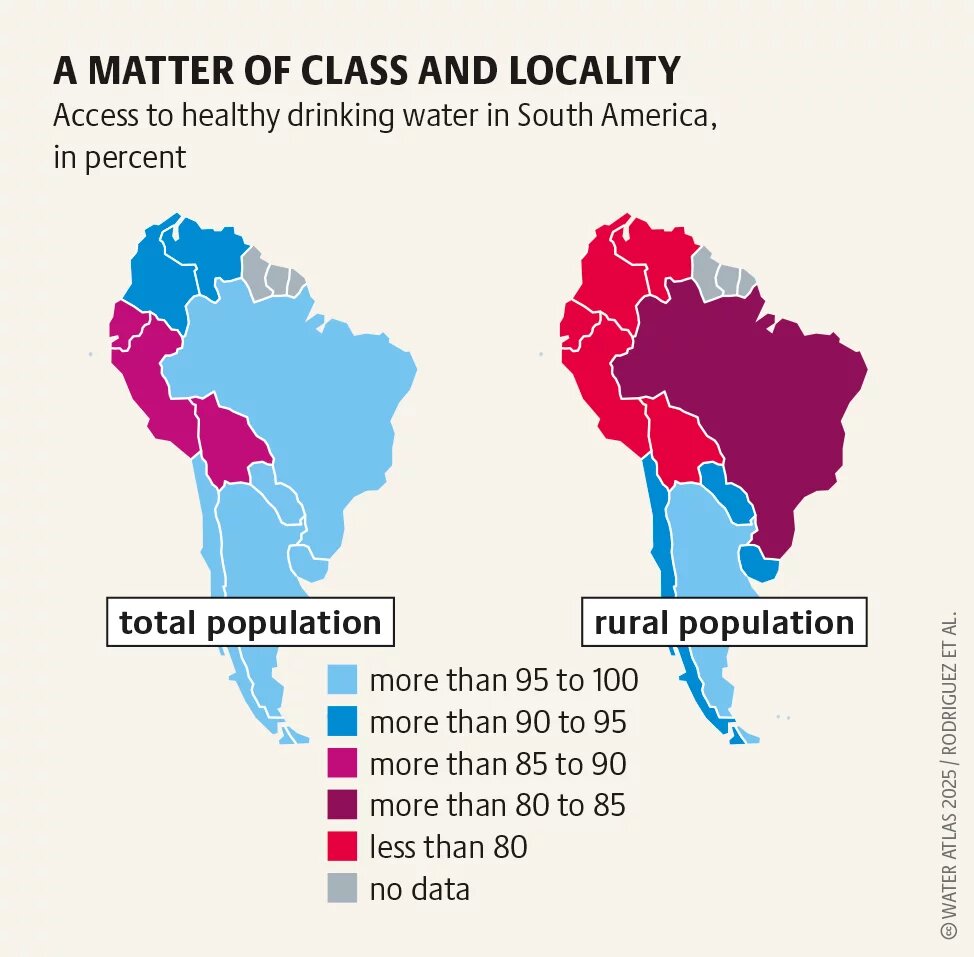

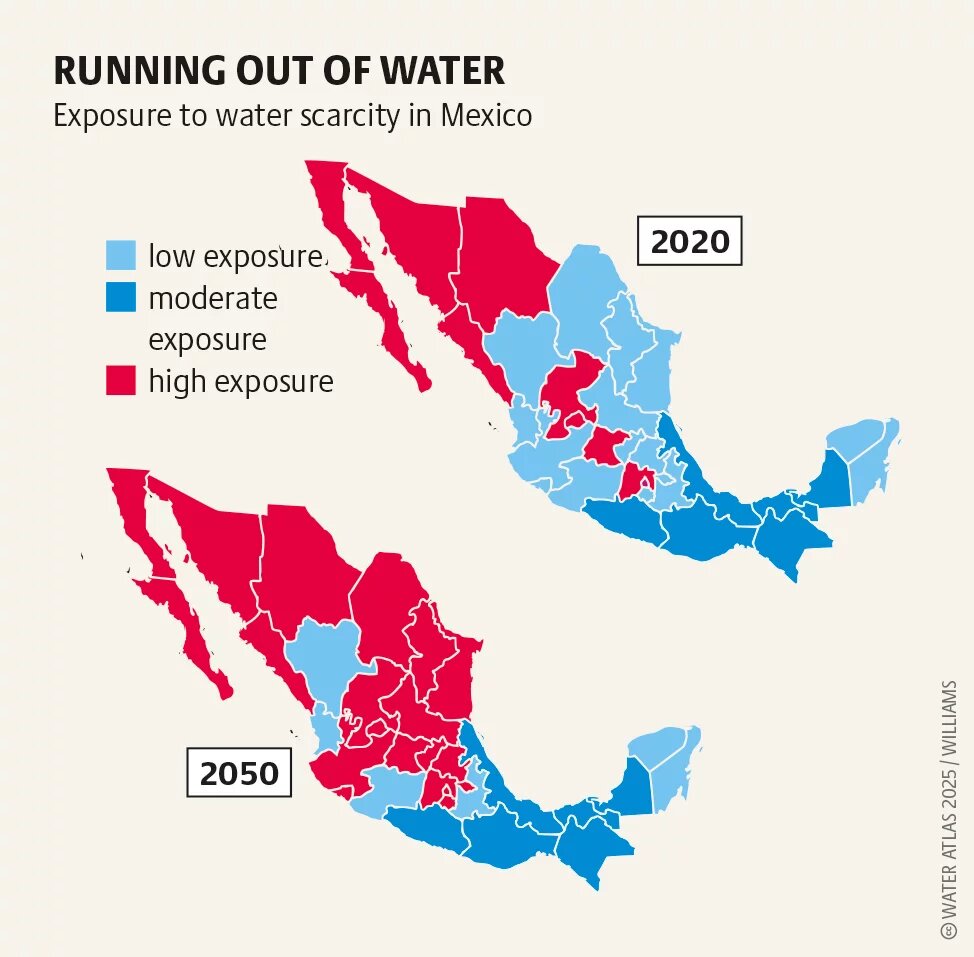

Thanks to its geographical location, varied topography and range of climatic zones, Colombia is one of the wettest countries in the world. Over 3.2 million Colombians living in rural areas are without access to safe drinking water. Over the past 170 years, Colombia’s glaciers have shrunk by 90 per cent, and large areas of the high-altitude paramos have been lost due to the climate crisis and the expansion of mining and energy activities into ecologically rich regions. These declines pose a huge risk because the glaciers and the páramo ecosystem store water and regulate the water cycle, making them very important for the water supply to the population living at lower altitudes.

Water is either scarce or polluted in numerous places across Colombia. The Bogotá River is highly contaminated by wastewater; the Atrato River is polluted by illegal mining; and the Medellín River is fouled by commercial and industrial effluent. The Magdalena – the country’s largest river – and the tributaries of the Amazon and Orinoco, which supply water to Colombia’s most vulnerable people, are also poorly managed.

The government’s approach to water access has largely been business-oriented. Public utilities are required to recover their costs through tariffs and to prioritise profitability. Their relationship with users is treated as a commercial arrangement, rather than water being seen as a right – even though the constitution requires the state to guarantee access to water.

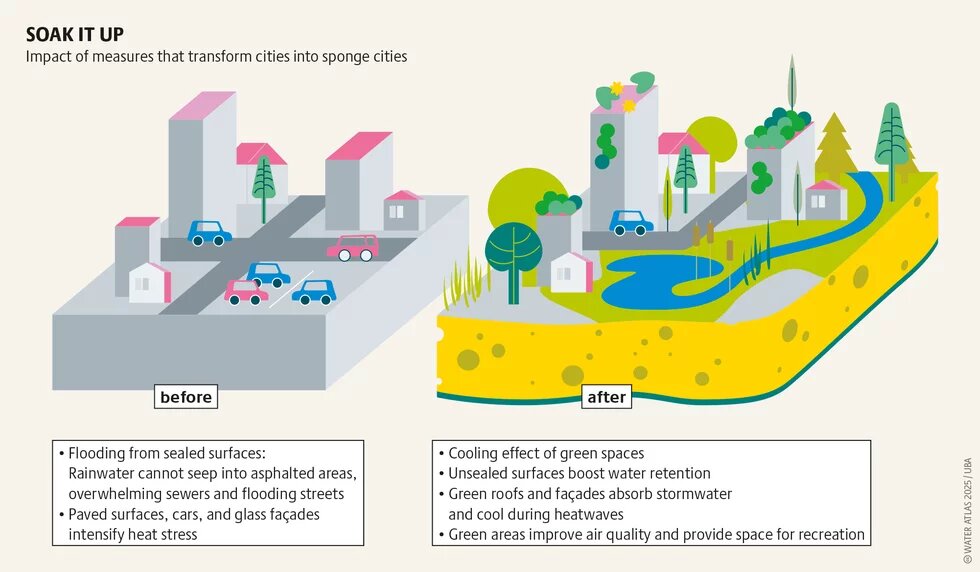

Community water management offers an alternative. In this model, local communities play a central role in water management, making decisions and ensuring water supplies. This work is typically organised through village-level community action boards or user associations, which operate independently of state or private utility providers. The community organisations hold open assemblies where users make decisions collectively. They set priorities, agree on rules for water use, set tariffs based on solidarity principles, and organise the maintenance and protection of infrastructure. This model emphasises local knowledge, trust and accountability. It often includes environmental stewardship as a core principle.

In Usme, a rural district of Bogotá, several community water systems are managed by residential user associations. These associations ensure fair and continuous access to water through voluntary labour, shared responsibilities and democratic governance. Decisions are made in general assemblies, and much of the infrastructure is maintained through collective work efforts known as mingas. Similar community-led initiatives exist throughout Colombia. These networks support each other through knowledge exchange, legal assistance, and advocacy at the national level.

Those who benefit most from this model are rural and peri-urban populations, who are often excluded from conventional water services. Community management guarantees access to water in areas where powerful private actors claim land in pursuit of profit, and where the state has historically failed to provide public services. The community water groups do not just offer access to water; they also empower communities, strengthen their autonomy, foster social cohesion, defend common property against those seeking private gain, and promote sustainable water use.

Many community water managers have taken the lead in defending the environment against extractive industries. In Tasco, a town in the department of Boyacá in central Colombia, community water groups managed to stop the expansion of coal mining. They are now demanding compensation for the environmental damage the mining has caused. The National Network of Community Aqueducts, an organisation with nearly two decades of experience advocating community-based water management, is at the forefront of developing and defending legal and public policy to protect water as a public community good.

Community water managers have deepened their collaboration and developed a shared strategy. Their Water Mandate is a joint proposal that calls for water to be treated as a common good. It promotes the democratic governance of the commons and supports a holistic, long-term approach to water management. It advocates for the government to recognise the autonomy of communities, support and respect them, and provide investment and technology transfer.

The Water Mandate is based on four key principles. First, it challenges the notion that human rights are neutral or disconnected from the way water is governed. Second, it calls for an end to fragmented, sector-specific approaches to water supply and environmental management. Third, it promotes the re-democratisation of water governance as essential for the realisation of fundamental rights. Finally, it affirms the right of communities to manage water in their own areas and to use it to meet their basic needs. By doing so, community-led water governance stands as a credible alternative to market-based models – one that prioritises equity, participation and long-term sustainability.