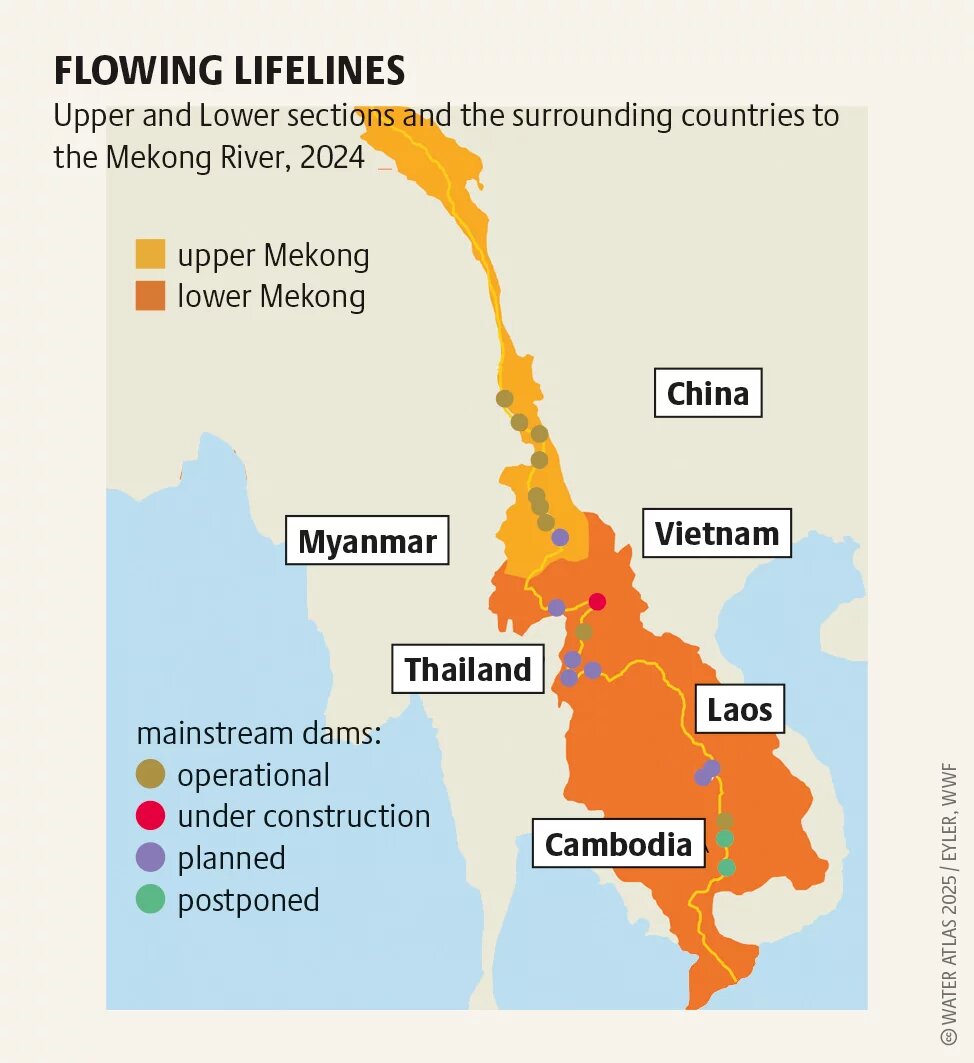

The Mekong, one of the world’s most biodiverse rivers, breathes life into vast ecosystems. Flowing through six countries, it links cultures, livelihoods, and landscapes. But as dams multiply, pollution intensifies, and currents slow, its natural rhythms break down.

Over its nearly 5,000-kilometre course, the Mekong River – known as the Mother of Waters – nurtures riparian ecosystems; from its headwaters on the Tibetan Plateau through China, called the Lancang, to its lower basin. Through Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, the river threads its way between rocky outcrops, rapids, sediment bars, wetlands. It meanders and broadens into alluvial floodplains in Cambodia, before becoming the Sông Cuu Long as it empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam.

Seasonal rhythms shape the river’s ecosystems as the Mekong rises and ebbs. During the flood season, the river, responsible for 70 to 80 percent of the total annual flow, surges, reverses, and expands its tributaries, including Southeast Asia's largest inland freshwater lake, the Tonle Sap in Cambodia. The phenomenon is uniquely known as the flood pulse: a seasonal heartbeat that sustains the river’s ecology.

Wetlands correspond to the river’s rhythms: they rise and fall with the ebbs and flows. They are vital to fisheries and aquatic life, covering more than 18 million hectares in the lower Mekong basin. Riverine plants' roots anchor themselves against turbulent currents and offer refuge where migratory fish can breed, spawn, and shelter their young. Of over 1,000 identified fish species —and counting — at least one-third migrate seasonally, and 200 are found nowhere else on the Earth. Fishers adapt their gears to the fish, the ecosystems, the seasons, and then they wait. The river’s abundance is woven into livelihoods, spirits, and stories. The magnificent Mekong Giant Catfish, one of the world's largest freshwater fish species, is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List yet remains prominent in legends and memories.

As the dry season approaches, fish seek refuge in mainstream deep pools or tributary wetlands. Mid-channel bars and rapids emerge while plants’ young leaves bud, fruits ripen, and migratory birds come for food and breeding. Floodwaters replenish the soil with sediments and nutrients. Riverside farmers prepare their land and sow seeds along the retreating waterline. In northern Thailand, freshwater green algae known as kai grow on smooth river stones when the water clears. Although the Mekong has marked the border between Thailand and Laos since French colonial rule in the early 20th century, women still cross boundaries to collect kai for consumption and income. The river’s cycle continues as the rains return, ushering in the next flood season.

For millennia, the Mekong has sustained riverine communities and civilisations. Today, more than 65 million people live in the Lower Mekong Basin, representing a great diversity of ethnic groups and Indigenous People. Riverside towns, including the capitals of Laos and Cambodia, rely on the Mekong for transport, trade, tourism, and agriculture. The Mekong’s inland fisheries rank among the most productive of the world, supplying nearly 80 percent of local animal protein.

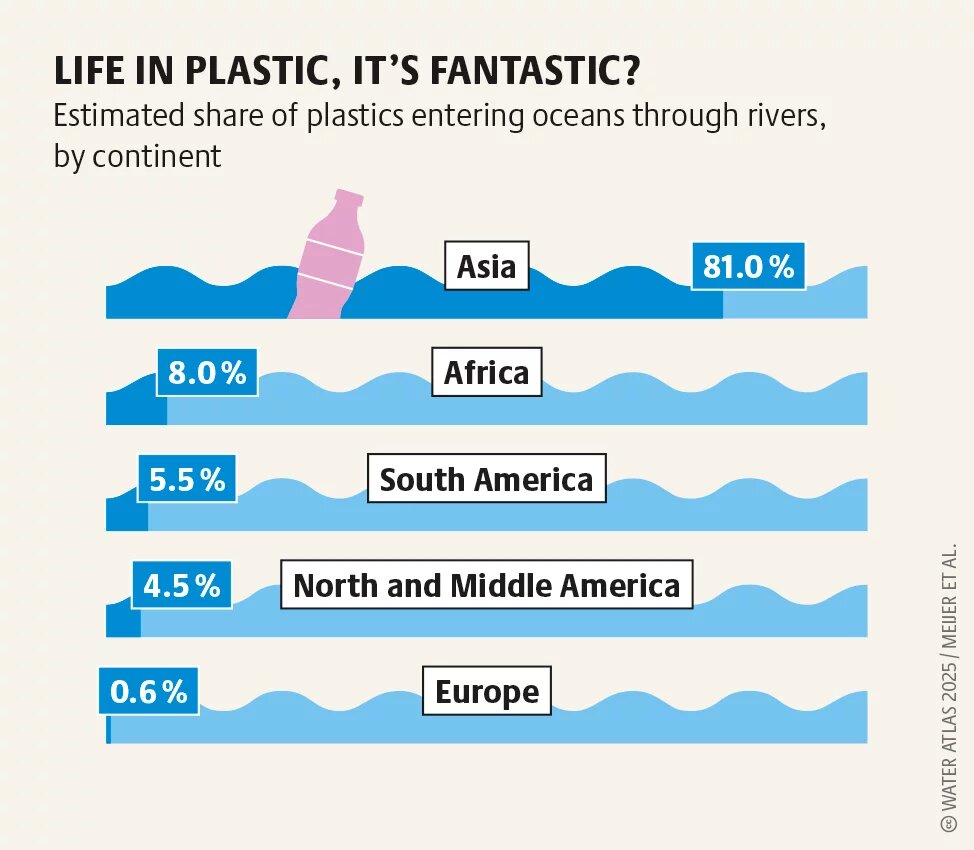

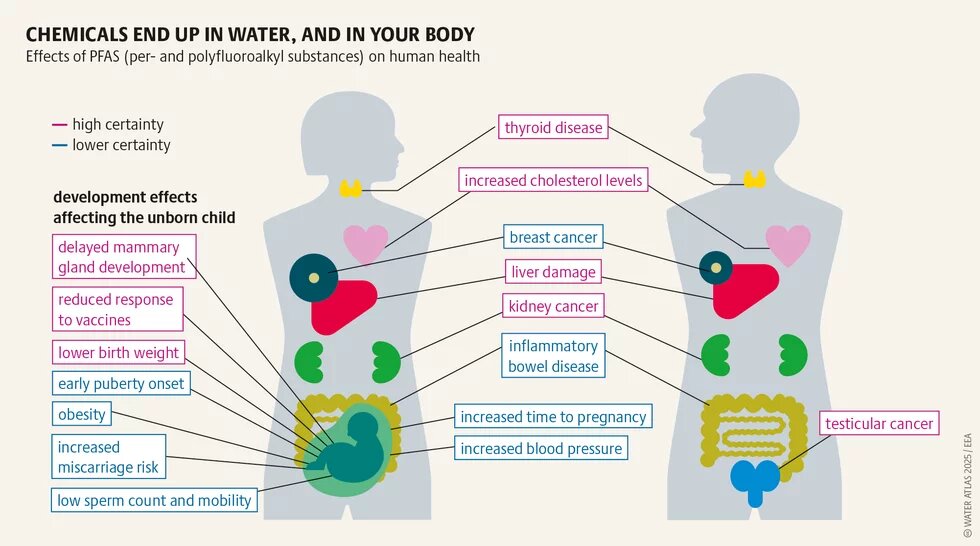

The Mekong forms the backbone of regional economic growth. Its riverbed is dredged for sand, a key ingredient for concrete construction. The velocity of its strong currents attracts hydropower dam projects, turning flow into electricity, and profit, across mainland Southeast Asia. But while rising electricity demands drive industry, urban growth, and intensive agriculture, the Mekong also carries tons of debris, microplastic, and effluents ocean. One example comes from the Chi River, a tributary of the Mekong in Thailand, where scientists discovered that 73 percent of 100 sampled fish, belonging to eight species of barbs and catfish, contained microplastics in their stomachs. In March 2025, the Mekong River finds itself in another dire predicament. Kok River, one of its tributaries, is contaminated by arsenic exceeding WHO safety threshold from unregulated rare earth mining operations in Shan State, Myanmar. Fisher folks observed visible abnormalities of fish caught from Kok and Mekong rivers.

Dams and damming disrupt the river’s seasonal rhythm and block the natural flow of sediments. Daily water level swings, triggered by cascade dams a thousand kilometres away in China, are felt downstream. Sudden releases during the dry season flood crops, disorient fish and plants, and damage fishing boats and local tourism. Dams block fish migration, forcing fishers to adopt other livelihood strategies. Sediments and organic matter are essential nutrients for soils, plants, fish, and humans, but they are trapped and contaminated. In extreme cases, the rusty-brown Mekong turns blue, starved of sediments and nutrients.

In 2022, Thailand’s administrative court dismissed a lawsuit by 37 community representatives opposing the Xayaburi Dam in Laos, built and financed by Thai developers. Local fishers, women, and community leaders, citing the transboundary impacts on ecosystems and livelihoods, demand equal say alongside experts in decision-making. After unusually blistered, red-spotted fish appeared in the Kok River in March 2025, communities sought collaboration with academics and authorities to address cross-border rare earth mining impacts. Through grassroots initiatives – conservation zones, sediment monitoring, youth engagement, and regional advocacy – they defend both the Mekong’s right to flow freely and the rights of nature.