Populism, nationalism, and an intensifying rivalry between the United States and China are testing the cooperation within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As its 10 member States battle the effects of Covid-19 amid political and territorial crises, the group has struggled to overcome internal differences and address profound external challenges.

This study is part of the series "Shaping the Future of Multilateralism - Inclusive Pathways to a Just and Crisis-Resilient Global Order" by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung's European Union and Washington, DC offices.

Multilateralism, as defined by Robert Keohane in 1990 and more recently by Hanns Maull in 2020, is not only a coordinated arrangement among States, but also reflects joint commitments to common goals, values, and methods. This certainly describes the intent of ASEAN since its founding in 1967. But today’s intense global challenges, combined with ASEAN members’ reluctance to “interfere” in issues they deem to be internal affairs or domestic politics, hinder prospects for deeper, more productive multilateralism.

These patterns have been evident as ASEAN seeks to harness its collective efforts to mitigate the impact of the pandemic. The organization reflects the spreading populism and unilateralism of individual member States, and the influence of the major powers’ rivalry on relations within the association. Most recently, ASEAN’s anemic reaction to the military coup in Myanmar has illustrated the need for a stronger, united response.

ASEAN’s multilateral initiatives amid the Covid-19 pandemic

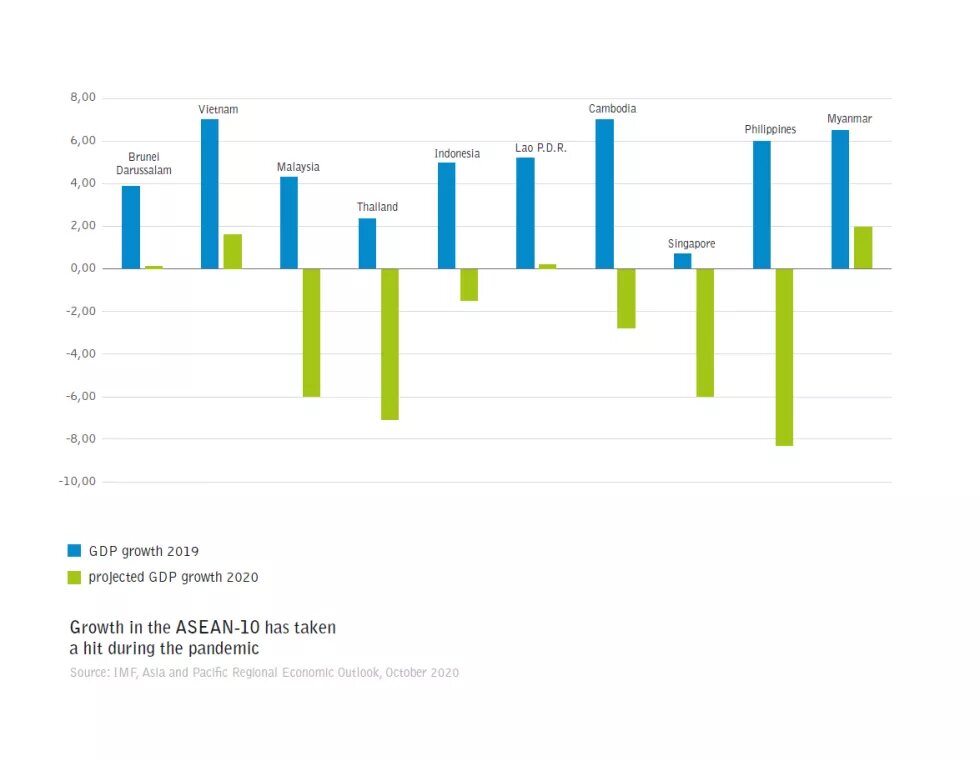

Southeast Asian nations, like the rest of the world, are battling both the pandemic and its socio-economic ramifications. The impact in both cases demands collective mitigation efforts by ASEAN. As of June 2, 2021, authorities across the region had reported more than 4 million cases of infection and 79,193 deaths from Covid-19. Of the 10 countries in ASEAN, Indonesia recorded the highest number of cases by that date (1,826,527) and the most deaths (50,723). The Philippines had the most cases per 100,000 inhabitants (1,158) and the greatest number of deaths per 100,000 (20). According to a January report in Business Times, the pandemic reduced economic growth of the ASEAN-10 by 7.8 percentage points in 2020, with the Philippines worst affected at -14.4 points, followed by Malaysia and Thailand at just over 10 points each. Even the least affected – Vietnam, Brunei, and Myanmar – dropped by 4 to 5 percentage points.

Beyond – and because of – such health and economic effects, the pandemic has undercut multilateralism across the globe. The World Health Organization (WHO) stumbled in its initial efforts to coordinate initiatives to mitigate the crisis. Despite being alerted to the spread of the coronavirus by the end of December 2019, the WHO waited until Jan. 30 before declaring an international emergency and declared the outbreak a pandemic only on March 11, 2020, by which point 118.000 cases and more than 4,000 deaths had been reported worldwide. The United Nations Security Council was silent in the beginning – only in July 2020 did it manage to adopt a resolution supporting the Secretary-General’s appeal for a global ceasefire that he had issued in March to help unite efforts to fight Covid-19 in the most vulnerable countries. And member nations of the European Union for weeks ignored plea from officials in Rome for an EU Civil Protection Mechanism, as Italy initially faced the pandemic’s worst onslaught; some EU countries responded to their fellow members by closing borders internal to the bloc.

Likewise, ASEAN tended toward unilateralism and failed to coordinate. Malaysia closed its borders, which impacted the causeway connection with Singapore. Vietnam also closed its borders with Laos and Cambodia, which prompted the latter to shut its borders in retaliation.

Still, ASEAN took a number of multilateral actions on the pandemic that are important for a number of reasons. First, the region contributes significantly to global economic output. ASEAN countries’ total GDP in 2019 was US$3.2 trillion, essentially making the grouping the fifth-largest economy after the United States, China, Japan, and Germany.

Second, while the ASEAN region has achieved rapid economic growth and development, the expansion has been uneven, and the pandemic further weakened lax intra-regional economic ties. Lastly, ASEAN relies heavily on trade with both the United States and China, and the rivalry between the two world powers and their different approaches to the pandemic had a bearing on the economic consequences and responses in Southeast Asia.

The regions’ dire pandemic situation prompted ASEAN to convene several high-level meetings to discuss ways to mitigate the outbreak and rescue members’ economies. In February 2020, before the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, the ASEAN Defense Ministers issued a statement pledging joint efforts, especially through military medical collaboration. This was followed by a video conference in March of the region’s health ministers in the ASEAN Plus Three format (APT – the association plus China, Japan, and South Korea). They focused on improving the sharing of information, data, and expertise on prevention of infection.

The many significant meetings that followed included the Special ASEAN Summit in April 2020. There, the governments established the Covid-19 ASEAN Response Fund for joint purchases of medical equipment, and pledged deeper cooperation within the bloc and with non-ASEAN countries and international organizations to “maintain socio-economic stability.” At the 36th ASEAN Summit in June 2020, leaders expressed their “strong commitment to alleviate the adverse impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on people’s livelihood[s], societies and economies.” They said they would implement “a comprehensive recovery plan with a view to improving stability and resilience of the regional economy, preserving supply chain connectivity, while staying vigilant of a second wave of infections.”

Looking at the agenda and discussions of these first few meetings during the early months of the pandemic, ASEAN seemed to be somewhat more focused on the socio-economic implications of the pandemic than the immediate health threat and its cross-border nature. This likely was due to two factors: firstly, the novelty of the situation, as leaders still had little understanding of the potential scope and length of the crisis; secondly, the preoccupation of most ASEAN members with the pandemic’s effects within their own countries and their preference to act unilaterally by, for example, closing borders.

Even at the 37th ASEAN Summit in November 2020, the grouping still seemed to prioritize the economic aspects of the pandemic – for example, by planning to establish an ASEAN travel corridor “to facilitate essential business travels among ASEAN member states.” The summit endorsed an ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework (ACRF) consisting of five strategies. Two of them focused on issues that seemed to have little immediate connection to the pandemic, particularly its health effects: managing intra-ASEAN market- and broader economic integration and digital transformation, including exploring the development of an ASEAN small- and medium-sized enterprise recovery facility.

In contrast to the outsized focus on economics at its initial internal meetings, ASEAN’s outreach to global communities such as the EU and the United States seemed more balanced, with significant attention to the health threats of the pandemic. In March 2020, the co-chairs of the ASEAN-EU Ministerial video conference on Covid-19 emphasized in their final statement their commitment to cooperate in addressing the pandemic comprehensively and effectively, taking into account the different levels of development of health systems in Southeast Asia, while still paying attention to the region’s socioeconomic development.

As part of Europe’s global response to the pandemic, the EU has provided more than EUR800 million to support the preparedness and response capacities of ASEAN, focusing particularly on public communication and research. The EU support to Indonesia, for example, included digital solutions for tracking the government’s Covid-19 expenditures, which helps ensure their transparency and accountability.

A similar primary focus on the pandemic’s health effects emerged from a Special ASEAN-U.S. Foreign Ministers’ Meeting on Coronavirus Disease in April 2020, chaired by Lao PDR Foreign Minister Saleumxay Komnasith and U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. ASEAN welcomed a significant role for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in capacity building for ASEAN’s health workers. One example cited was a USAID-Vietnam partnership to strengthen and expand infection-control protocols in Vietnamese hospitals. ASEAN also applauded the United States for its provision of more than US$35.3 million of assistance to help counter the spread of the coronavirus in the region. Both parties planned to continue working together under the ASEAN Health sector, ASEAN Coordinating Council Working Group on Public Health Emergencies (ACCWG-PHE), and the WHO’s International Health Regulations mechanisms.

Southeast Asia has been especially vulnerable to the pandemic, considering its peopleto-people connectivity and integrated supply chains, trade, and investment. While it is understandable that each country focused initially on urgent national responses, mitigating the effects of pandemics by definition calls for international cooperation. Effective pandemic management demands both national health governance and multilateral cooperation. ASEAN, despite its limitations, seems to be doing what it can to coordinate collective actions.

ASEAN amid major powers’ rivalry: Covid-19 and the South China Sea

The pandemic also affected ASEAN’s position vis-à-vis the two major global powers vying for influence in the region, the United States and China, especially as relations between the two deteriorated further amid the viral outbreak. Yet ASEAN member States reacted differently to the escalating tensions based on each country’s longstanding relations with the two powers.

Cambodia, for instance, has very strong ties with China, which accounts for 43 percent of its foreign direct investment and US$9 billion of bilateral trade. Chinese investors also support Cambodia’s garment industry, which represented 15 percent of its 2019 GDP, generating 750,000 jobs. Meanwhile, the Philippines, which earlier had hinted at a possible “separation” from its long-time ally the United States in favor of China, now seems ready to rekindle its relations with the U.S. in light of the Whitsun Reef standoff with China in March of this year. Observers also say that the Philippines will restore the Visiting Forces Agreement that sets out the terms under which U.S. forces are stationed in the country. Hence, ASEAN struggled, as it often does because of its disparate membership, to maintain the middle ground.

As early as February 2020, and more so after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Wuhan in March 2020, Beijing began donating medical supplies and testing kits to ASEAN countries. The Philippines, Myanmar, and Cambodia were among the first in line, possibly due to the close ties between China and the leaders of the Philippines and Cambodia and, in the case of Myanmar, its strategically important location sharing a border with China and offering access to the Indian Ocean, according to researcher Lye Liang Fook. Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei also received significant material assistance from China. Vietnam and Singapore received limited material assistance and only in the later stages, possibly because they had less need, considering their relative success in handling the pandemic.

In addition to material assistance, China shared experience and expertise in fighting the outbreak, via training of medical workers in the region. For example, China sent civilian medical teams to five ASEAN countries – Cambodia, China’s strongest ally in Southeast Asia, as well as Laos, the Philippines, Myanmar, and Malaysia. Laos and Myanmar even received military medical teams, considered better-trained than their civilian counterparts and offering more political clout, according to Lye.

Also in February 2020, ASEAN and Chinese foreign ministers met in Laos and issued a statement pledging to share information, technical guidelines, and solutions for the outbreak. They also committed to stronger cooperation “to ensure that people are rightly and thoroughly informed” about the disease. And they planned further policy dialogue through existing joint mechanisms involving health ministers and senior officials on health development to implement an ASEAN-China memorandum of understanding on health cooperation. A follow-up statement in May from a meeting of ASEAN and Chinese economic ministers called for joint efforts to alleviate the pandemic’s impact on regional and global trade and investment, especially in terms of the ASEAN–China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA).

In April 2020, the health ministers of China, Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN issued a joint statement committing to sharing technical, material, and financial support to sustain national health systems. In a speech delivered at the 73rd World Health Assembly in May 2020, Xi pledged US$2 billion of aid worldwide over two years for Covid-19 response and “economic and social development in affected countries,” as well as a humanitarian supply hub in China in coordination with the U.N. and provision of any Chinese-made vaccine as a global public good.

Meanwhile, the United States also made its moves. In May 2020, the U.S. State Department outlined joint work on the pandemic with Indo-Pacific partners as well as additional efforts going forward. The latter included plans to share best practices, mitigate the effects of border closures, maintain necessary transportation links, strengthen regional and global supply chains, advance development of vaccines, promote transparency of public-health data, improve the pandemic response of multilateral institutions, and strengthen governance and the rules-based international order. The United States pledged US$57.5 million of humanitarian aid to ASEAN, with US$7.5 million especially allocated to Indonesia.

But despite the overwhelming need to focus on accelerating and improving the pandemic response, geostrategic territorial disputes over the South China Sea continued unabated. In April 2020, the same month authorities in Beijing were sending medical assistance to ASEAN countries to fight the coronavirus, China was engaged in a battle of a different kind against some of the same countries. In one case, Vietnam said a Chinese maritime surveillance vessel rammed and sank a Vietnamese fishing boat. Later that month, China and Vietnam allegedly harassed a Malaysian state oil company exploration vessel. The U.S. accused Beijing of taking advantage of the region’s understandable preoccupation with the pandemic to further exploit its neighbors. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi denied the allegations, and in turn accused the United States of “politicizing” China’s actions.

The U.S.-China political dueling continued through the summer and into the autumn. At one point, in September, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi declared, “We don’t want to get trapped by this rivalry.” The Philippines, for one, had been hedging its bets. That March, U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo visited Manila and proclaimed for the first time that the U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty applies to armed attacks in the South China Sea, as “part of the Pacific.” In July, Pompeo gave full support to the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling in support of the Philippines’ case that China’s territorial claims contravened international maritime law. In reality, this support might have made the Philippines stance vis-à-vis China a bit tricky, considering the island nation’s economic dependence on trade with China and, in the immediate instance, on China’s humanitarian and other assistance during the pandemic. Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte made a point of repeatedly thanking Xi for Covid-19 assistance, while simultaneously flip-flopping over the Visiting Forces Agreement with the United States.

At its 37th ASEAN Summit in November 2020, the association expressed its hope that its long-awaited code of conduct for activities in the South China Sea would be substantive and effective. Having been announced at a 2018 ASEAN ministerial meeting as forthcoming and having survived a first reading by ASEAN and China in 2019, it is due to be finalized this year. It will be almost 20 years after the November 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea that laid the groundwork for a formal code. In light of the ongoing pandemic, however, it remains to be seen when finalization could occur.

In this era of the coronavirus, with its humanitarian aid and vaccine diplomacy, China seems to be seeking to heighten its leverage in Southeast Asia. Although the new U.S. administration of President Joe Biden might alter the geopolitical dynamics in the region, the push and pull between the United States and China, especially on the South China Sea issue, will continue to dominate relations within ASEAN and between the bloc and these global powers. And China is quickly gaining ground on another front: its economic and trading power.

A new Asian trading bloc

Despite the raging pandemic, ASEAN member states and five dialogue partners – Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea – in November 2020 signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to form the world’s largest trading bloc, amounting to about US$26 trillion worth of economic activity, 30 percent of global GDP, and 28 percent of global trade. Brookings Institution analysts Peter A. Petri and Michael Plummer estimated that RCEP might add US$209 billion a year to global income and US$500 billion to world trade by 2030.

The pact illustrates the aspirations of ASEAN economies and their partners for economic cooperation amid uncertainties caused by the maneuvering of the great powers and by the pandemic. Although the trade bloc often is referred to as “China-led,” ASEAN was the driving force, brokering deals that brought in India, New Zealand, and Australia in 2012. “Without such 'ASEAN centrality,' RCEP might never have been launched,” according to Petri and Plummer.

ASEAN’s multilateralism and the Myanmar military coup

The February 2021 coup in Myanmar has posed a challenge to ASEAN multilateralism. On the one hand, the coup represents a democratic rollback, and since the 2007 charter, ASEAN has pushed for democratic forms of governance, rule of law, and fundamental respect of human rights. Yet ASEAN also has a mutual non-interference principle that opposes member States meddling in each other’s internal affairs.

Myanmar’s 2015 election was considered especially groundbreaking, as it was the country’s first national vote since a nominally civilian government was introduced in 2011, ending almost 50 years of military rule. However, although that earlier vote had ushered a landslide victory for Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party, the military-drafted constitution stipulated that unelected military representatives take up 25 percent of seats in the parliament and have a veto over constitutional changes. The military dubbed this “disciplined democracy.”

Since that 2015 election, Myanmar has conducted three more: the 2017 and 2018 by-elections and the November 2020 general election. That most recent vote gave NLD another massive win, with 396 of 476 seats in parliament, an even larger margin than in 2015. The military’s proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, won only 33 seats. The military declared voter fraud, detained Myanmar leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, and declared a state of emergency for one year. It said it would hold a rerun of the election once the state of emergency ended.

The Feb. 1 coup drove tens of thousands of people into Myanmar’s streets to protest the power grab. They were met with a severe crackdown by security forces, with violence escalating as the standoff extended for months. As of mid-May, more than 700 people had been killed by Myanmar’s security forces, and thousands had been detained.

The international outcry included widespread condemnation and U.S. and U.K. sanctions against the leaders of the coup and Myanmar military conglomerates. Yet ASEAN was unable to speak with one voice. Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin immediately on Feb. 4 deemed the political situation in Myanmar a “step backwards in the country’s democratic process,” and warned it could “affect peace and stability in the region.” Similarly, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan on March 1 said ASEAN would tell the Myanmar military it is appalled by the violence and would call for the release of the country’s elected leaders, including Suu Kyi, and for the two sides to talk.

Also in February, both Malaysia’s Muhyiddin and Indonesian President Joko Widodo called for a special ASEAN meeting on Myanmar. Shortly after the coup, ASEAN Chair Brunei urged “the pursuance of dialogue, reconciliation and the return to normalcy in accordance with the will and interests of the people of Myanmar.” The statement emphasized “the purposes and the principles enshrined in the ASEAN Charter, including the adherence to the principles of democracy, the rule of law and good governance, respect for and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms.”

Meanwhile, following Indonesia’s statement that it would seek support from other ASEAN member states to hold Myanmar to its promise of new elections within a year, anti-coup protesters gathered in front of the Indonesian embassy in Yangon, demanding that Indonesia respect the results of last year’s election. This is understandable: with steps limited to engagement with the junta and pressing the military for elections in a year’s time, ASEAN would fall short of its own expressed values and the demands of the protesters, which included the immediate reversal of the coup and the recognition of the NLD victory in the last election.

Moreover, in the beginning of the coup, some ASEAN member states such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Philippines called the coup Myanmar’s “internal affair.” This reaction was significantly different from the strong statements made by Malaysia and Indonesia. Such divided responses pose a challenge to ASEAN’s credibility in its efforts to foster democracy and stability in the region.

On April 24, in accordance with Indonesia’s March appeal for a meeting and in a move that was unprecedented for an association that otherwise takes pride in its “noninterference” approach, ASEAN finally convened a high-level meeting in Jakarta on the Myanmar crisis. Attended by leaders of 10 ASEAN countries, including Myanmar’s junta leader Sen. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the meeting established five points of consensus. First, that there should be “an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar;” second, that the parties in Myanmar should seek a peaceful solution to the crisis via “constructive dialogue;” third, that Brunei, this year’s ASEAN Chair, would appoint a special envoy to mediate in the Myanmar crisis; fourth, that ASEAN would provide humanitarian assistance to the country; and fifth, that the special envoy would travel to Myanmar to meet with all parties in the crisis.

Despite these five points of consensus, observers are concerned such steps won’t do much to ease the crisis in Myanmar, especially because there has been no clarity on how to engage with the elected NUG government, which in reality enjoys wide support from Myanmar’s people. Within its limitations, however, ASEAN made a significant first step in coordinating a focused effort towards peace and stability in Myanmar. Whether or not the junta will adhere to the five-point consensus, however, remains to be seen.

Fostering multilateralism the ASEAN way

Throughout the pandemic, while ASEAN struggled to respond adequately to the health and economic crisis as well as to ongoing geostrategic competition and new tensions that arose in the region, it nevertheless also opened opportunities to deepen and foster multilateralism. There are several aspects to highlight.

First, while some observers may lament the seemingly slow and hamstrung way that ASEAN has responded to the outbreak, the organization is not a supranational body like the EU, and does not have independent executive authority. Thereby its primary mode of functioning is to reach consensus, which relies on the cooperation and goodwill of its member States. The statements emerging from ASEAN meetings during the crisis show at least a recognition of the need to coordinate efforts across the region and to continue fostering multilateral diplomacy among the member States and with partner countries such as China and the United States.

Second, with regard to the U.S.-China rivalry, ASEAN faces the challenge of maintaining the middle ground between the rivals, a conundrum exacerbated by elevated tensions during the pandemic. Even in “normal” times, ASEAN is perpetually caught in a tug of war, particularly on issues related to territorial disputes in the South China Sea. During the coronavirus crisis, each major power also competed to increase its leverage in the region by providing humanitarian aid and technical assistance to ease the effects of the pandemic. In all cases, ASEAN will face continuing challenges to its impartiality and its centrality to its members, as each leans toward one major power or the other.

Third, this year’s military coup in Myanmar and the difficulty ASEAN faced in uniting behind a common response illustrates the differences among member States in their understanding of what constitutes “internal affairs.” A military coup against an elected government is without doubt a democratic rollback and challenges the values stipulated in the 2007 ASEAN Constitution.

In short, with its initiatives and mechanisms, ASEAN has sought – though with difficulty – to overcome the profound differences among its members and the deep challenges confronting them. After decades of experience, the association continues striving to contribute to a rules-based and multilateral international order.

Reference list:

Arsyad, Arlina, “Jokowi’s call for Asean meeting on Myanmar a surprise, bold move,” The Straits Times, 24 March 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/jokowiscall-for-asean-meeting-a-surprise-bold-move

ASEAN, “The Founding of ASEAN,” https://asean.org/asean/about-asean/history/

ASEAN Briefing, “Covid-19 vaccines roll outs in ASEAN & Asia – Live Updates,” https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/covid-19-vaccine-roll-outs-in-asean-asia-live-updates-by-country/

ASEAN Key Figures 2020, https://www.aseanstats.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ ASEAN_Key_Figures_2020.pdf

BBC, “Myanmar: Journalists who fled coup face Thailand deportation,” BBC, 11 May 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-57067130

Channel News Asia, “ASEAN chair Brunei calls for ‘dialogue, reconciliation and return to normalcy’ in Myanmar,” Channel News Asia, 1 February 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/myanmar-asean-aung-san-suu-kyi-military-coup-14087150

Chong, Terence Tai Leung, Xiaoyang Li & Cornelia Yip (2020) “The impact of COVID-19 on ASEAN,” Economic and Political Studies DOI: 10.1080/20954816.2020.1839166.

CNBC, “ASEAN to tell Myanmar military it is ‘appalled’ by violence, says Singapore minister,” CNBC, 1 March 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/02/asean-to-tell-myanmar-military-it-is-appalled-by-violence.html

CNN Philippines, “PH suspends termination of Visiting Forces Agreement with US – DFA," CNN Philippines, 2 June 2020, https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2020/6/2/locsin-VFA-termination-suspension-.html

De Haan, Jarryd, “Pompeo and Marsudi in South China Sea Discussions,” Future Directions International, 12 August 2020, https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/pompeo-and-marsudi-in-south-china-sea-discussions/

Ebbighausen, Rodion, “Myanmar coup: ASEAN split over the way forward,” Deutsche Welle, 29 March 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/myanmar-coup-asean-ties/a-57042503

Huang, Yukon, “China is hostage to a rules-based multilateral system,” Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, 10 September 2020 https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/09/10/china-is-hostage-to-rules-based-multilateral-system-pub-82679

Heydarian, Richard Javad, “The true significance of Pompeo’s South China Sea statement,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, 4 August 2020, https://amti.csis.org/the-true-significance-of-pompeos-south-china-sea-statement/

Heydarian, Richard Java, “Little Sign of Duterte’s promised separation from the US as China-Philippines relations crumbles,” South China Morning Post, 23 April 2021 https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3130407/little-sign-dutertes-promised-separation-us-china-philippines

Idrus, Pizaro Gozali “China ‘ready’ to include ASEAN in $2B Covid-19 aid,” AA, 19 May 2020 https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/china-ready-to-include-asean-in-2bcovid-19-aid/1857846

Keohane, Robert O., “Multilateralism: an agenda for research,” International Journal 45.4 (1990): 731-764 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002070209004500401

Lye Liang Fook, “China’s Covid-19 assistance to Southeast Asia: uninterrupted aid amid global uncertainties,” ISEAS Perspective No.58, 4 June 2020 https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2020-58-chinas-covid-19-assistance-to-southeast-asia-uninterrupted-aid-amid-global-uncertainties-by-lye-liang-fook/

Pitakdumrongkit, Kaewkamol, “ASEAN’s perspective on economic recovery,” Brookings, 17 December 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/12/17/aseans-perspective-on-economic-recovery/

Suvannaphakdy, Sithanonxay, “Measuring the impact of Covid-19 on economic growth in ASEAN”, Business Times, 18 January 2021, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/asean-business/measuring-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-economic-growth-in-asean

Maull, Hanns, “Multilateralism Variants, Potential, Constraints and Conditions for Success,” SWP Comment 2020/C 09, March 2020, doi: 10.18449/2020C09 https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2020C09_multilateralism.pdf

McKeever, Amy, “Here’s what we’ll lose if the US cut ties with the WHO,” National Geographic, 10 July 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/07/whatwe-will-lose-if-united-states-cuts-ties-with-world-health-organization/

Petri, Peter A. and Michael Plummer, “RCEP: A new trade agreement that will shape global economics and politics”, Brookings, 16 November 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/11/16/rcep-a-new-trade-agreement-that-will-shape-global-economics-and-politics/

Porter, Tom, “Trump boasted about holding a rally without social distancing and mocked Democrats for observing coronavirus measures,” Business Insider, 9 September 2020 https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-rally-boasts-skirting-coronavirus-measures-north-carolina-2020-9

Suy, Heimkhemra, “No simple solution to China’s dominance in Cambodia,” East Asia Forum, 26 December 2020, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/12/26/no-simple-solution-to-chinas-dominance-in-cambodia/

Tollefson, Jeff, “How Trump damaged science – and why it could take decades to recover,” Nature, 5 October 2020 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02800-9

VOA News, “Myanmar anti-coup protesters return to streets after observing general strike,” VOA News, 23 February 2021, https://www.voanews.com/east-asia-pacific/myanmar-anti-coup-protesters-return-streets-after-observing-general-strike

Xinhua, “RCEP to boost regional trade, investment amid pandemic: Philippine trade chief,” Xinhuanet, 16 November 2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-11/16/c_139520103.htm

Yeung, Jessie and Sharif Paget, “China and WHO acted too slowly to contain Covid-19, says independent panel,” CNN, 22 January 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/18/asia/who-covid-review-panel-china-intl-hnk/index.html