In the EU, an Energy Union is emerging from a bewildering array of packages, policies, projects and proposals. They map the shift from concern over how energy markets function to efforts to promote renewables and curb greenhouse gas emissions.

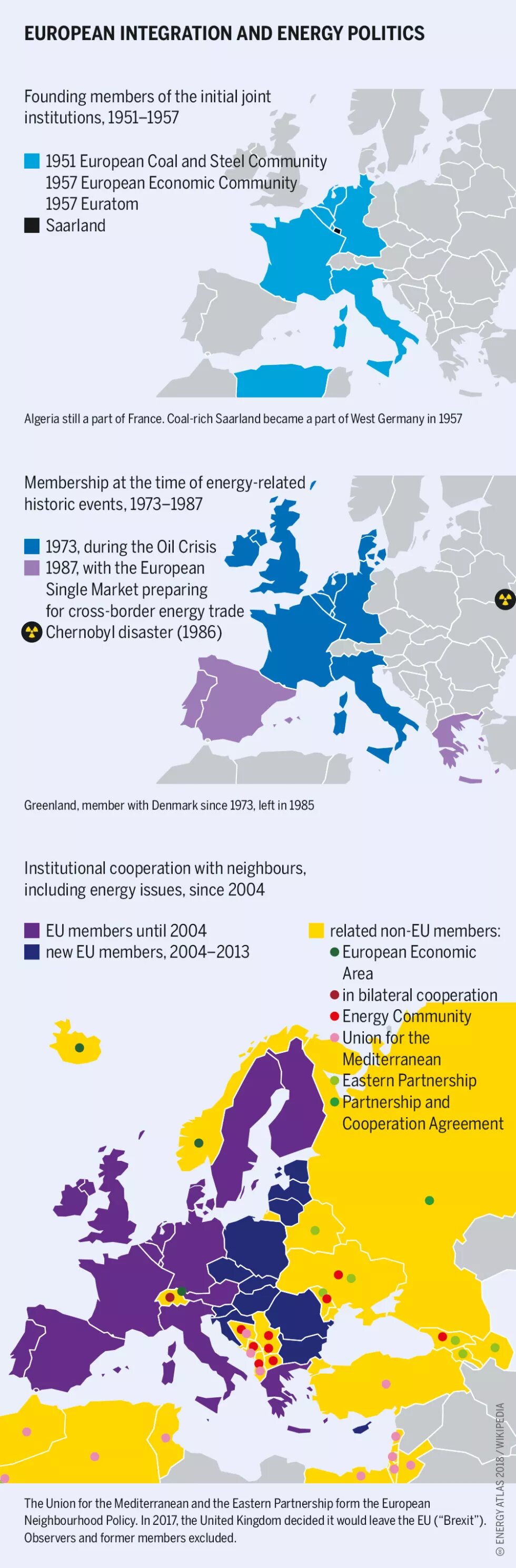

Energy has played a major role in the history of the European Union. Coal was the first fuel to be exploited; signed in 1951, the Treaty of Paris established the European Coal and Steel Community. With the signing of the Euratom treaty in 1957 to promote nuclear power, energy was once again the backbone of European integration. The economic base of energy cooperation was further strengthened with the Treaty of Rome in 1957 that created the European Economic Community, the predecessor of today’s EU.

Energy-supply issues dominated the early years of European integration. However, governed by protectionist policies, national energy markets remained largely isolated from one another. Spurred on by the 1973 oil crisis, Europe’s leaders developed a more coordinated approach to jointly tackling energy shortages. But the Single European Act of 1987 was the first serious attempt to deepen integration and remove barriers to cross-border energy trade.

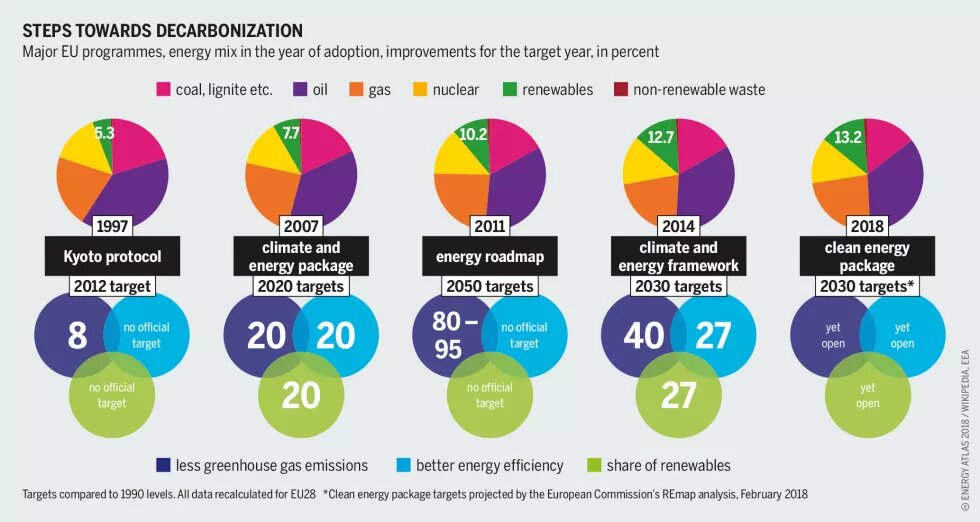

The realization that humans were influencing the climate came in the 1980s. In the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the EU committed to an 8 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2012 compared to 1990 levels. In the same year, the Amsterdam Treaty included sustainable development as a cross-cutting objective.

A major obstacle to cross-border energy trade was the monopolistic structure of the national markets for generation and transmission, preventing third parties from accessing the grid. To overcome this, in 1996 and 2003, the EU adopted the first electricity directives that aimed at increasing competition in the power market and ensuring a free choice among electricity suppliers. Similar directives for gas were issued in 1998 and 2003. The third energy market package in 2009 aimed to break up vertically integrated energy utilities.

The 2009 Lisbon Treaty, for the first time, included a separate section on energy. This outlined the objectives of EU energy policy, namely to, “ensure the functioning of the energy market; ensure security of energy supply in the Union; promote energy efficiency and energy saving and the development of new and renewable forms of energy; and promote the interconnection of energy networks.”

In the past decade, climate threats have increasingly been a driving force in the EU’s energy policy. An energy and climate package agreed in 2007 set binding sustainable energy targets for 2020. These are a 20 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions, a 20 percent share of renewables in final energy consumption, and an indicative target of 20 percent improvement in energy efficiency.

In 2014, the EU adopted its 2030 energy and climate framework that called for a greenhouse gas reduction goal of at least 40 percent, at least a 27 percent share for renewables in the energy sector, and at least a 27 percent improvement in energy efficiency. These targets form a basis for the Clean Energy Package currently being negotiated, which lays out the legal groundwork for future energy policy. But these cuts are still not steep enough to fulfil the EU’s commitments under the Paris Agreement and to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius.

Europe imports 54 percent of its energy. Yet the European Commission has limited competency in its external energy policies. Member states have sovereignty over foreign and security matters, and they find themselves in different positions in terms of their reliance on imports and on different suppliers and transit countries. The 2004 enlargement of the EU gave a new push for a more coordinated external energy policy, mainly because the new eastern members were dependent on Russian gas supplies. The European Neighbourhood Policy, launched in the same year and revised in 2015, sets the framework for how the EU engages with its neighbours to the east and south in advancing its sustainable energy goals. The Energy Community, signed in 2005, aims to extend the EU energy market rules to non-members in southeastern Europe.

2005 also saw a commitment by EU leaders to develop a coherent energy policy with three pillars: competitiveness, sustainability and security of supply. The repeated gas disputes between Russia and Ukraine in 2005–6, 2008 and 2009, as well as geopolitical tension in Northern Africa and the Middle East leading to the increasing vulnerability of the external energy supplies, have reinforced the need for such a policy.

The shift towards renewable energy holds untapped potential to reduce the continent’s dependence on external suppliers and enhance its energy security. Europe is beginning to look inwards and to drive forward the development of its internal energy market. The Energy Union, a project launched in 2015, tries to bring the 2030 climate and energy framework and the energy security strategy under one roof. The Paris Agreement of the same year committed the EU to deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. The “Clean energy for all Europeans” package of 2016 aims to align EU internal energy legislation with its Paris commitments.

Overall, energy policy is shifting from a phase of fragmentation to a period of gradual synchronization between member states and the EU. Energy lies at a crossroads between climate objectives, national interests and supranational regulation, sectoral dynamics and geopolitical conflicts. EU energy policy is also undergoing a major change. We are witnessing not only a shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, but also to new ownership models, and increasing decentralization and democratization of energy supply and distribution. Europe has a historic mission: to serve as a global model for energy transition and green innovations, and to lead the way in curbing global warming.