What will be the real impact of the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention? What effects will this accession have on foreign policy?

The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence represents the first piece of legislation for preventing and combating violence against women and girls that is legally binding at regional European level. The Convention entered into force in August 2014, after ratification by ten States, eight of them members of the Council of Europe. It imposes obligations on States with regard to the prevention of these forms of violence, protection for victims, criminal prosecution of those guilty of unlawful conduct and integration. By imposing these obligations, all the measures contained in the Convention can form part of an integrated and coordinated set of policies that provide a global response to violence against women and domestic violence.

Contribution of the Convention to the legal framework pertaining to violence against women

Currently, all the member states of the European Union (EU) have signed the Convention and the EU is in the process of accession. This article briefly explains the progress of this process and explores the impact that the accession may have on the legal framework of violence against women, evaluating whether this is the best step that could have been taken, or whether there are other more appropriate measures for strengthening the framework.

Process of accession and effects

In February 2014 the European Parliament called on the Commission to begin the process of accession “once the consequences and the added value of this had been evaluated”. The accession process began on June 13, 2017 with the signing of the Convention by the EU Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality. After the signing, the accession requires the consent of the European Parliament, which must approve the necessary legislation before it comes into force.

The accession has been presented by the European institutions as an example of their commitment to combat violence against women, both globally and within its territory, and as enhancement of the existing legal framework and its capacity to act. It has also been said that the EU accession will guarantee complementarity between nations and the EU, and will bolster the ability of the former to play a more effective role in international forums such as the Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO) [1].

Without wishing to dampen institutional enthusiasm, it is necessary to calculate the potential impact of the accession on the difficulties that exist in a region where legislative shortcomings and weaknesses in state systems for protection and justice in cases of violence continue to exist. On the other hand, the integration of the Convention into the legislative framework of the Union and its capacity to have a direct effect on its legal system are in doubt.

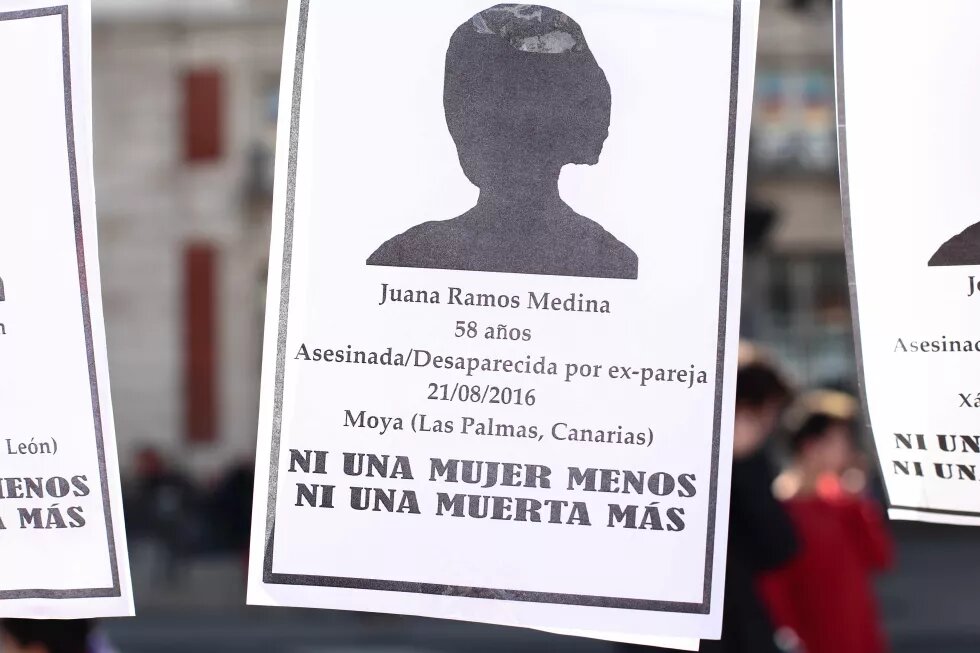

The legal systems of each one of the twenty-eight member states offer unequal protection for women against the different types of gender-based violence, which, moreover, are defined and dealt with in different ways in each country. The situation is exacerbated by the absence of directives that define and regulate violence against women. Although the mere existence of directives does not ensure the harmony of legislations in EU countries, as illustrated by the case of human trafficking, it is a solid first step.

This accession represents a strong political gesture that positions the EU as the global leader in the defence of human rights, and could guarantee against the risk of incoherence or double standards with regard to violence against women. However, legally, the most appropriate measure for combating gender violence would be the passing of a Directive, as recommended in a study commissioned by the European Parliament. Effectively, a European Directive about violence against women would, for the first time, have the capacity to create a common understanding about the definition and category of this violence in each Member State; it would have a direct effect on the legislation of States; and it would incorporate mechanisms for stronger sanctions than those laid down by the Convention.

The question now is whether European institutions will continue to take the necessary steps to legislate on this matter and make a real change in the lives of millions of women and girls in the European Union.

Influence of the accession on the EU’s foreign policy

The significance of the accession in terms of the EU’s foreign policies, which are the responsibility of the European External Action Service (EEAS), is an interesting question. Reducing violence against women has become one of the priorities of development policies and humanitarian action plans of the EU, while one of the three objectives of the new EU Gender Action Plan 2016-2020 is for women and girls to live a life free from violence. The struggle against gender-based violence is mentioned in some treaties between the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific group of states (ACP) as a way to reduce the HIV problem and as a necessary element in the process of building peace, and the prevention and resolution of conflicts.

It is to be hoped that the accession strengthens the EU’s inter-regional dialogue with regions that already have legal instruments to combat violence towards women, such as the pioneering Latin American Belém do Pará Convention, and that the European External Action Service integrates the obligations contained in the Istanbul Convention into its foreign policies.

__________________________________

[1] GREVIO is the monitoring mechanism of the Convention.

[2] An example of this are the cases where the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that there were violations of the European Convention on Human Rights by EU Member States: Slovakia, Italy, Romania, Lithuania, Austria, France, Cyprus, Greece, Belgium, Sweden, Poland, UK, Bulgaria, Hungary, Spain, Ireland, Slovenia - in cases of violence towards women