Agroecology is a successful concept which promotes farming methods that are attuned to local ecosystems. It is already used for growing rice worldwide.

The globalization of food production through multinationals has created a physical and psychological distance between consumers and farmers, i.e., between what we eat and where it comes from. Food arrives packaged on supermarket shelves with little trace of its rural origins. But more and more people are questioning this dominant food system; they are critical of how industrialized food is produced and how little we know about it. A growing movement of pioneers around the world is working to change the way we produce and consume food. They are trying to make our food systems more socially just, environmentally friendly and independent from big corporations – from farm to fork.

The idea of agroecology is not new: farmers and social movements have for decades been working on more environmentally and socially friendly alternatives to industrial agriculture. Now, research institutions, civil society, the United Nations and a few governments are starting to adopt this concept. In the 2015 Declaration of the International Forum for Agroecology, social movements agreed on the principles and methods to achieve this vision. But it still has a long way to go before it becomes mainstream.

Agroecology is often confused with ecological farming or sustainable intensification – an approach that aims to produce more with fewer resources. But agroecology is more, and different. It questions the logic and power relations that underpin current agricultural production. It instead promotes small-scale farming that is attuned to local ecosystems. It is not only a set of agronomic techniques; it is a political, social and transformative process. It offers tools that give people the right to define their own food, agriculture, livestock and fisheries systems, and the policies that affect those systems as part of an international movement. It seeks not to fine-tune industrial agriculture but to replace it: not conformation but transformation.

The agroecology approach imitates and optimizes natural processes by using local resources effectively, and by recycling nutrients and energy on the farm. This reduces the farm's dependence on purchases from big agricultural corporations. Industrial fertilizers are not needed to keep soils healthy: plant residues, manure and trees provide the soil with the nutrients it needs. Instead of pesticides, mixed crops keep pests under control. Crops are grown together with plants that either repel unwanted insects or attract useful ones. This "push–pull" method is widely used.

SRI - The System of Rice Intensification

Rather than buying hybrid seed from corporations, farmers produce their own seed, improve it and distribute it through seed banks and exchange networks. Their seeds are well adapted to the particular environment and climate in each place, and maintains high agrobiodiversity on farms. Agroecological methods are well-suited to small farmers as they are adapted to local conditions. The System of Rice Intensification is an example of the agroecological approach. Rice seedlings are transplanted at a wide spacing to promote root growth. Instead of continuous flooding, the paddies are inundated intermittently to a shallow depth; weeds are controlled mechanically.

The System of Rice Intensification is practised by ten million smallholder farmers in over 50 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Yields are 47 percent higher than in conventional farming, and the method maintains soil fertility over the long term. Organic matter fertilizes the soil and supports microorganisms. Instead of growing a single crop in a continuous monoculture, farmers grow several crops at the same time in a field, or one after another.

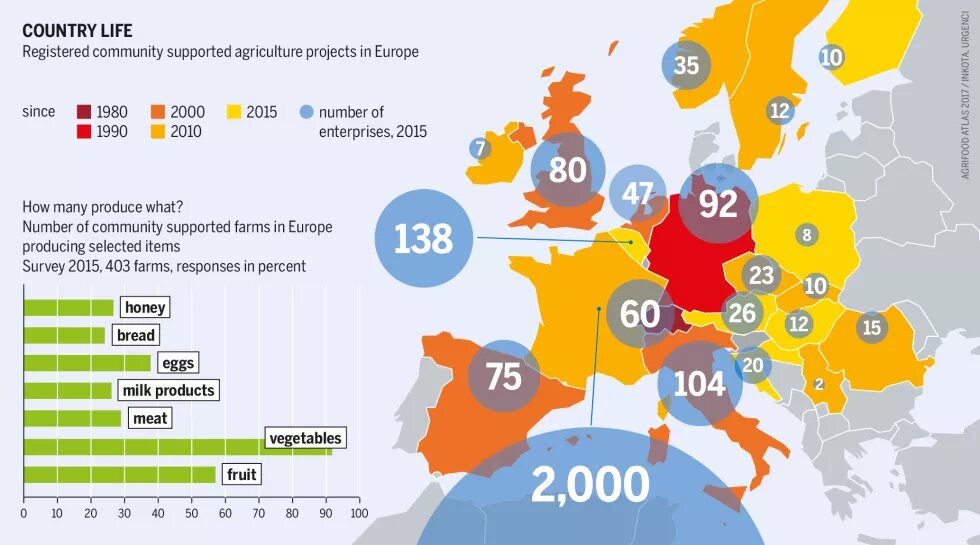

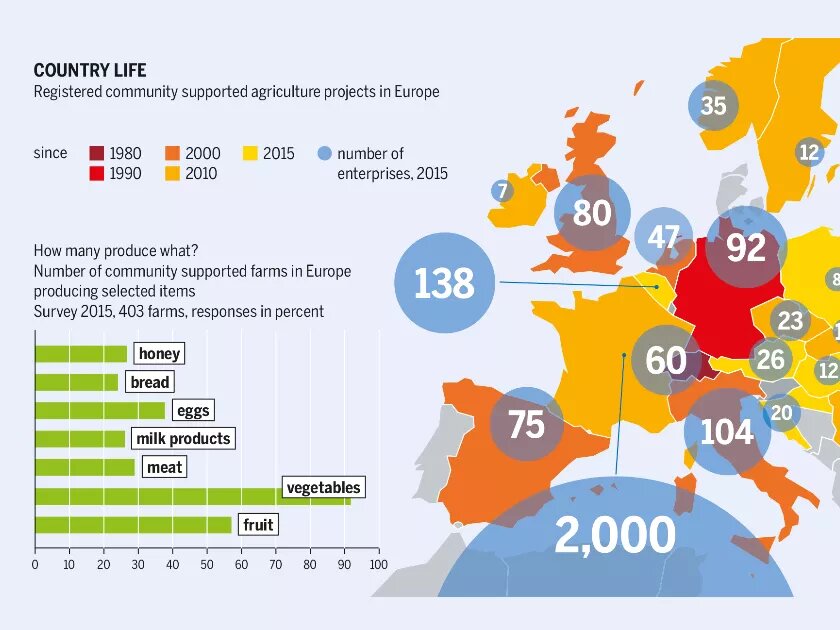

"Community supported agriculture" offers an alternative to buying food in the supermarket

This provides different sources of food and income and reduces the risk of crop failure. Consumers can become independent from big corporations too. Across the world, various initiatives connect consumers to farmers. In Europe and the United States, "community supported agriculture" offers an alternative to buying food in the supermarket. Consumers and producers get together and plan what to grow on the farm. The harvest and risks are shared. Consumers do not think of themselves as consumers, but as co-producers. They cover part of the risk of production, enter into long-term purchase commitments, and pay fair prices. In Europe, some 2,800 such initiatives supply half a million people with food.

Many weekly farmers' markets in urban areas do not rely on intermediaries. In the global north, farmers sell locally produced food directly to consumers. In the developing world, markets supported by local authorities allow farmers to sell produce grown in an agroecological way. Farmers in Bogotá, the capital of Columbia, earn 25 percent more profit at such markets, even though the prices are 30 percent lower than in the shops.

Other initiatives in both developed and developing countries bring actors in the food chain together to realign their local food system. Such "food policy councils" play an important role in various countries: Canada, the UK and the USA. They act as platforms for civil society, local companies, scientists, politicians and local governments. In Toronto, the food policy council agreed on a plan to increase farmers' incomes, provide more school meals and promote health education. In Germany, four such initiatives are active now.

Similar initiatives exist in the developing world. In 1993, the National Council for Food Security in Brazil helped develop a national school nutrition programme supported through a public procurement policy. Every day it provides 45 million children and young people with food, grown mainly on smallholdings. Jointly shaping local food supply chains can make them sustainable and democratic, freeing producers and citizens from the chains of agribusiness.

» You can download the entire Agrifood Atlas here.