The US coal industry is losing market share to gas and renewables. The nation’s dirtiest fuel is giving way to cleaner alternatives. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

In mid-July 2015, a major Midwest power company made a momentous announcement: five of its pollution-heavy coal-fired power plants in Iowa will soon undergo transition to natural gas or shut down entirely. Iowans were shouldering an estimated $15 million in healthcare costs from the plants’ air pollution, and the state, which already gets one-third of its power from wind, is now closer to a clean-energy future. Even though gas is not a renewable energy, most of the time it is still marginally cleaner than coal and other fossil fuels.

But the phase-out also marked a historic national milestone: it was the 200th coal plant shutdown announced since 2010 – meaning that 40 percent of all US coal plants are now headed for retirement. The American coal industry is suffering, knocked down by market forces that have given a decisive edge to natural gas and renewables. These are the result of the technology known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, which has led to vast new quantities of natural gas, a rapidly declining price of renewable energy, and innovations in financing for renewable energy.

Electricity utilities are moving away from coal power, and coal companies are heading towards bankruptcy. In July 2015, Walter Energy and Alpha Natural Resources were the most recent in a long list of companies filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The companies that are still operating are not faring much better. Peabody Energy reported a net loss of over $1 billion for the quarter ending in June 2015. This is a gargantuan economic shift.

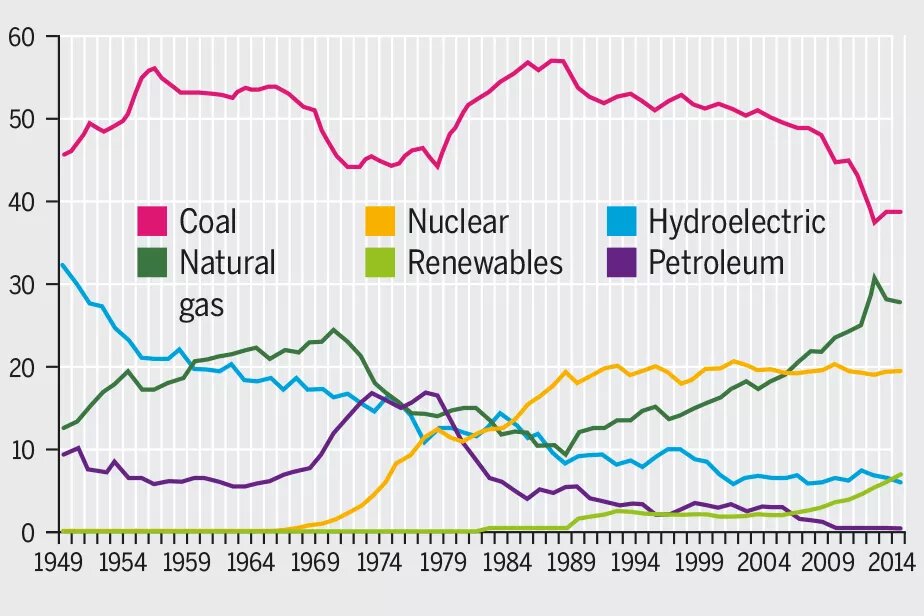

Throughout the 20th century, coal was the undisputed champion of American energy, providing well over half the power consumed nationwide. Starting in the mid-2000s, that share began to tumble, and today coal is down below 40 percent of the nation’s power mix. In April 2015, for the first time in US history, more of the country’s electricity came from natural gas than from coal.

Coal’s decline is a sign of vital progress. Coal-fired power plants are the nation’s top source of carbon dioxide emissions, accounting for nine percent more CO2 emissions than all vehicles. In other words, the United State’s capacity to slow global warming is largely contingent on its ability to curb coal consumption.

That fact is a central tenant of President Obama’s climate policy, embodied in a new set of regulations that will likely form a key barrier to any prospect of a domestic coal resurgence. Known as the Clean Power Plan, the regulations will empower the Environmental Protection Agency, using authority from the Clean Air Act, to limit CO2 emissions from the power sector for both new and existing sources. Ultimately, the plan aims, by 2030, to reduce emissions from the nation’s existing power plants to levels that are 30 percent beneath those of 2005. The rules dictate to each state a unique target for reductions in its carbon intensity (i.e., emissions per unit of energy produced). States are free to meet the target any way they wish; some choose to retire coal plants.

Larger trends in the US energy market are ushering coal out the door, regardless of the president’s opinions about climate change. Another development is the failure of carbon capture and sequestration to materialize as an economically viable option. In 2015, the

Department of Energy cancelled two large-scale carbon capture and sequestration projects despite having spent huge amounts on them.

Conceived by President Bush in 2003, one of these projects, known as FutureGen, was intended to be the world’s first zero-emissions coal facility. Originally projected to be finalized by 2012, the project might end up costing taxpayers over $1 billion. While still going forward, the Kemper coal plant in Mississippi has been equally troubled. It is currently billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule.

The coal industry has been in trouble even without a price on carbon. An important court decision in Colorado could help pave the way for a price to be put on coal. A federal district court stopped the expansion of a coal mine due to the federal government’s failure to quantify the costs of greenhouse-gas emissions. The court found the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service had arbitrarily based their approval to expand mining exploration in the Sunset Roadless Area solely on the estimated economic benefits of the project; they had ignored the social costs of its potential contribution to global climate change. The court found the agencies violated the National Environmental Policy Act, which mandates that federal agencies take a “hard look” at the potential environmental impacts of a proposed project prior to making a decision. This could lead to the government being required to consider the social cost of carbon when approving leases.

Since 2007, production of natural gas from shale exploded thanks to the controversial extraction method known as fracking. According to federal statistics, since 2000, the volume of shale gas produced nationwide has grown over 1,800 percent. In spring 2012, gas prices hit an all-time low, and as a result, consumption of electricity from natural gas has grown 58 percent since 2000. Most of that growth – 90 percent, according to one recent analysis – has directly replaced coal. At the same time, renewable sources like wind and solar continue to surge as well, thanks to falling costs and tax incentives at local, state, and federal levels.

As the market for coal falls, coal production is also on a downward slope. In 2008, it entered its first long-term decline in history, and as of spring 2015 coal production was down to levels not seen since 1989. Meanwhile, since the beginning of that decline the coal-mining industry has shed at least 50,000 jobs, and now employs fewer than half the number of people who work in the US solar power industry.

One important upshot of these trends is that US CO2 emissions from the power sector are on the decline, falling 12 percent since 2008. Another is that US coal producers are increasingly looking to sell their product abroad. Coal exports are at record highs, with shipments bound mostly for Europe, Asia and Brazil. That trend has fuelled a new battle with environmental activists, who are campaigning aggressively against planned coal-export terminals in the Pacific Northwest.

The US coal industry isn’t dead yet; official projections show it playing a central role for decades to come. Still, it’s safe to say that the heyday of America’s dirtiest energy source has come and gone.