Coal is an important part of India’s energy mix, and consumption is rising quickly as the economy expands. Local production is not enough: strong demand is attracting imports from Australia and elsewhere. However, India has huge potential for renewable energy, especially solar and windpower. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

Of the 1.2 billion people worldwide without access to electricity, over 300 million live in India. Two-thirds of the 80 million households affected are located in villages that are nonetheless connected to the electricity grid. “Energy poverty” – the lack of modern, non-polluting forms of power – harms lives in numerous ways. Daily power shutdowns, known as “load shedding”, increase business costs, reduce efficiency and stop farmers from pumping irrigation water. Burning firewood, cow dung and kerosene pollutes the air indoors and causes respiratory problems, especially among women who do the cooking. Poor lighting means schoolchildren cannot do their homework in the evenings.

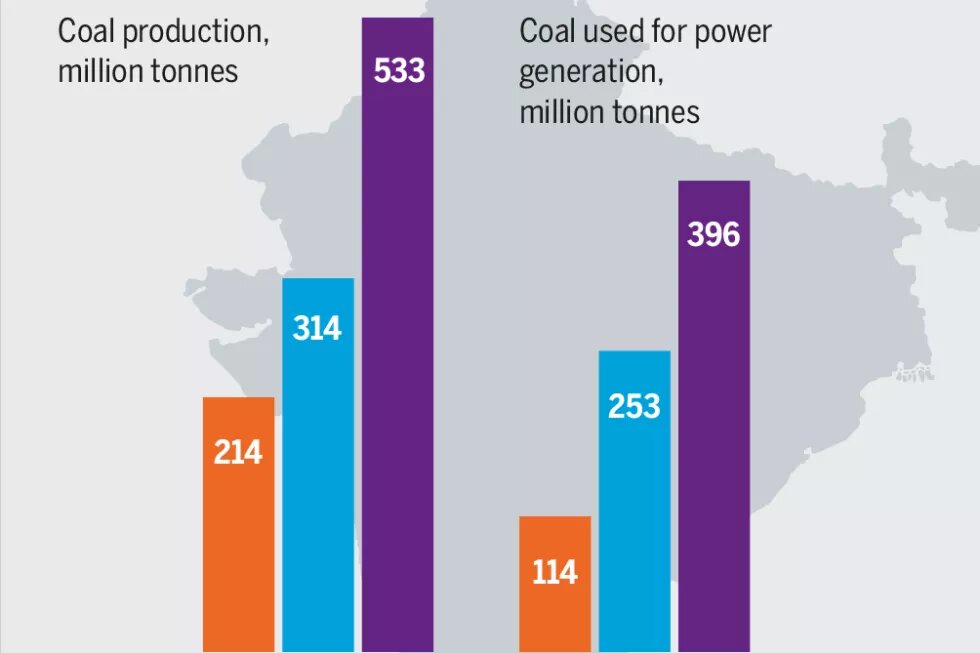

India has been able to reduce poverty alongside a massive expansion of coal use over the last two decades. Power production and the amount of coal consumed to produce it nearly quadrupled between 1990 and 2013. The percentage of the population living below the poverty line fell by about one-third, while the proportion of the population with access to electricity rose from half to more than three-quarters. Coal has alleviated India’s energy access problem and contributed to poverty reduction – though at substantial health, social and environmental costs. And yet each Indian consumes the equivalent of only 0.47 tonnes of oil a year: less than a third of the world average.

Coal provides more than half of India’s total primary energy, a share that is projected to decline only slightly by 2030. In 2013–14, the country consumed 740 million tonnes, more than 70 percent of it to produce power, and much of the rest to make steel and fertilizer. The government has targeted a coal consumption of 1 billion tonnes for 2020. Current consumption makes India the world’s second-biggest coal consumer, and number three in terms of total CO2 emissions, even though its per capita emissions of around 1.7 tonnes per person a year remain by far the lowest among the BRICS countries.

Much of India’s coal mining and many of its coal-fired plants, often situated directly on the mining sites, are located in forest areas inhabited by indigenous groups called Adivasi. Living on the fringes of India’s mainstream society, they are among the poorest communities in India, while bearing the brunt of the environmental destruction and pollution caused by the extraction of coal and other minerals. Large-scale coal mining and power plants in the Singrauli area in Madhya Pradesh have displaced local people and led to land grabs, the loss of forests and numerous health issues, including mercury pollution. Here, local protests recently stopped plans to expand mining in the Mahan forest. In the open-cast mining areas of Jharia, Jharkhand, uncontrolled underground coal fires have burned continuously for nearly a century. Also in Jharkhand, Maoist guerrillas fight the government; while claiming to defend local communities they themselves thrive on their own coal operations and on protection money paid by coal companies.

India has enormous coal reserves of 300 billion tonnes that could provide the country with energy for hundreds of years at current consumption rates. State-owned, Coal India is the single largest coal company in the world, with over 350,000 employees in 2013 and producing close to half a billion tonnes of coal in 2014–15. Together with numerous state-owned coal power plants and Indian Railways (which derives nearly half of its freight earnings from transporting coal) they constitute a veritable pro-coal lobby within India’s government institutions.

Still, national coal production lags behind official expectations, because of local resistance, outdated production techniques and the cancellation of licences for private mine operators after corruption allegations (known as “Coalgate”). Twenty-five years ago, nearly all the coal used in India was produced locally. Today, nearly one-quarter is imported, most of it from Indonesia, Australia and South Africa. In 2014–15, the import share was 19 percent higher than in the preceding year, and India may overtake China as the world’s biggest coal importer in 2015. To supply the growing import market, Indian companies have gone global. For example, the Adani company, which operates a coal power plant and India’s largest coal port in Mundra, Gujarat, wants to invest in large-scale mining in the Galilee Basin in Queensland, Australia. To handle exports to India, the company has leased the Abbot Point port and plans to expand it, endangering the Great Barrier Reef, a World Heritage Site.

India’s government views anti-coal and divestment campaigns as threats to national energy security and inimical to the country’s strategy of rapid economic growth. The government acts against local groups as well as international NGOs such as Greenpeace that advocates a rapid end to the use of coal worldwide. Other NGOs, such as the Centre for Science and Environment, argue that coal has to be phased out in the longer run, but may be required as a cheap energy option in the meantime. They lobby for increased efficiency and higher pollution reduction standards. A “green rating” environmental audit undertaken in 2014 revealed that many of the country’s coal-fired power plants perform very poorly. Even the best did not achieve more than “average” ratings.

Coal is likely to remain prominent in India’s power mix, but alternatives are being pursued as well. There are plans to build several additional nuclear power plants, as well as numerous dams especially in the Northeast; but they meet substantial opposition, particularly at the local level. India has a huge potential for solar energy, and in 2014, the government announced an ambitious plan to expand solar-generated capacity to 100 gigawatts by 2022, about three times the total current solar installations of countries such as China or Germany. From April 2015, the tax on coal was doubled to 200 rupees (about €3) per tonnes, and the proceeds will be used to promote renewables.

Energy poverty provides a potential for technological leapfrogging. Today nearly 97 percent of India’s 600,000 villages have a grid connection, however, due to poverty or erratic power supply, 43.2 percent of rural households still relied on kerosene for lighting in 2011. This is why businesses and NGOs see opportunities to establish small-scale solar installations and off-grid or micro-grid solutions based on solar power or small hydroelectric plants.