When the coal firms arrive, local people can expect forced removal and repression. Voluntary standards are of little help. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

Mining companies are accused of violating human rights more often than firms in other industries. John Ruggie, who served as the United Nations Special Representative for Business and Human Rights from 2005 to 2011, revealed that 28 percent of all complaints received by his office were directed against mining and oil/gas companies. Underground coal mines are particularly prone to safety lapses and poor working conditions. Open-cast mines violate the human rights to food and water, says Ruggie, and residents are often forcibly relocated.

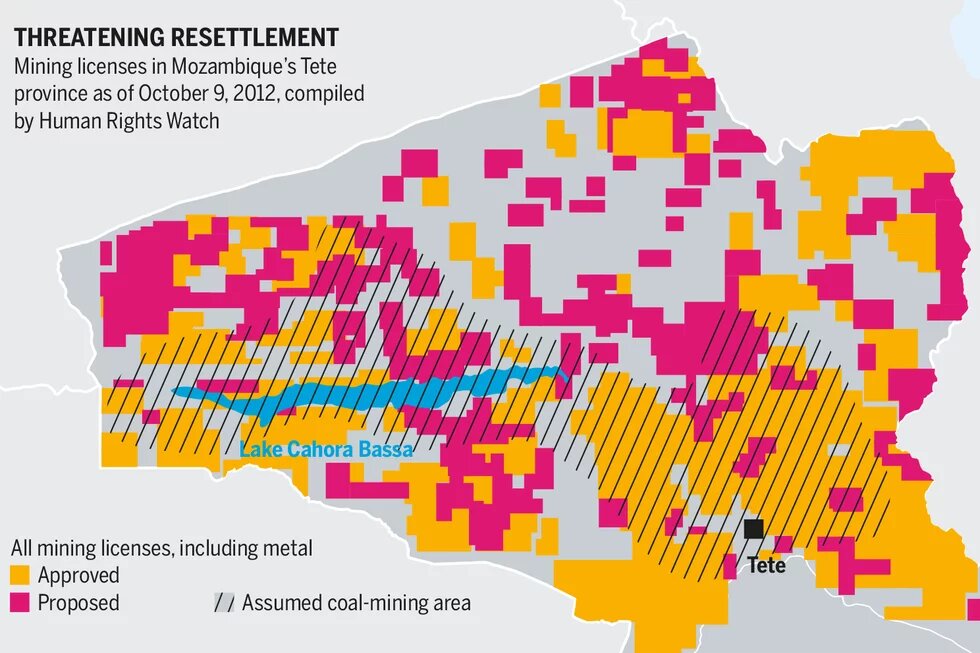

Open-cast mines eat into farmland, pastures and hunting areas. In Mozambique, coal companies from Brazil and Britain resettled more than 2,000 households between 2009 and 2012. These people were moved to barren, arid areas where they now find it hard to grow food. Worse still, the Indian company Jindal operates an open-pit coal mine without resettling the local communities, leading to serious health problems for residents who still live just one kilometre away. Water pumped out of mines is often discharged without adequate treatment. The dissolved toxic substances and waste oil it contains make it completely unusable. They pollute the groundwater and surface water of surrounding areas.

The Alta Guajira area in northern Colombia is very dry, but the Cerrejón coal mine there uses 17 million litres of water daily. In a region where people are faced with scarcity of water, the abundant use of water in the mine is regarded with disapproval. The United Nations recommend between 50–100 litres of water per person a day for personal and domestic use.

In northwestern Bangladesh, a planned coal mine at Phulbari threatens 130,000 people with relocation. Some 220,000 people fear losing their supply of clean water. Residents have been demonstrating against the mine ever since the plans were announced. In 2006, the Bangladesh Rifles, a paramilitary force, killed three people and wounded over 100 others. Each year, activists meet in memory of the victims. In 2012, the government tried to prevent this commemoration by banning gatherings of more than four people.

Companies in Colombia, Indonesia, Mozambique and South Africa have been accused of using brutal security personnel to protect their facilities. They use force against protesting workers, trade union activists and local residents. Resistance has been criminalized to weaken the protests and reduce support for them. In one example, paramilitaries murdered three trade unionists in Colombia in 2001. The victims’ relatives have accused Drummond, an American mining company, of employing the perpetrators as guards. Drummond denies responsibility and in early 2015 sued the victims’ lawyer in the United States.

Indigenous peoples are frequently affected by mining. The Dayak, an indigenous tribe in Indonesia, are fighting coal mining in their territories on the island of Kalimantan. Some communities there have been forcibly relocated more than once by mining activities. Colombia’s Cerrejón mine impacts a region where 45 percent of the population are indigenous people and 7.5 percent are descended from Africans. In Australia, coal mines are often found in Aboriginal territories. In Russia, open-cast mines surround the settlements of the Teleuts and Shors, Siberian Turkic peoples. The resulting dust and waste water have destroyed their hunting and fishing grounds. In Colombia, the Gunadule are now struggling against the same fate: the government has awarded a South Korean firm concessions to extract coal in their area, without consulting the local people.

Even if consultations are held before a mining project goes ahead, the agreements cannot be trusted. Many an undertaking to restore the land proves to be hollow. In Jharkhand, in India, where hard coal is mined in open pits, the overlying soil was stockpiled so it could be reused. But six years later, it had lost its fertility.

Most deaths in coal mining occur because safety and labour standards are ignored – itself a violation of human rights. Although the mining industry accounts for only about one percent of the global workforce, it accounts for eight percent of fatal accidents at work. In addition not all deaths are recorded officially, especially in the illegal coal mines of China, Colombia and South Africa.

Pneumoconiosis, or “miner’s lung” is an internationally recognized occupational disease, but Russia, India and South Africa do not publish data on the number of victims. In China, though, the Ministry of Health revealed that there were 23,812 new cases in 2010, half of them a result of coal mining. An international research team examined 260,000 cases of people who had died of the disease worldwide; 25,000 deaths could be linked to coal mining. Even if the disease does not kill, it can cause severe suffering. Patients can no longer work, thus condemning their families to poverty. They may have the right to claim compensation from the mining company, but a doctor must confirm their claim. Furthermore, payments are often delayed or insufficient.

Many mining areas are among the poorest parts of a country, even in the industrialized world. In the Appalachians, a mountain range in the eastern United States, poverty and mortality rates are significantly higher in coal-mining areas than elsewhere. Studies in several countries reveal that mining mainly benefits a small, mostly urban class, while rural people suffer. If coal is extracted for export, local people hardly benefit at all; on the contrary they are usually left with the toxic remains. Poverty also leads to child labour in coal mines. Around 400,000 children are working in the Indian state’s 15,000 mines in Jharkhand, many of them under often inhumane conditions.

Mining companies do respond to such accusations. The International Council on Mining and Metals, an association of 23 of the world’s leading mining companies, has published guidelines for respecting human rights and the rights of indigenous peoples. Some companies are improving health-care services and infrastructure. But the governments in many countries lack the will or ability to guarantee mining workers and local people the most important protection – that of the law.