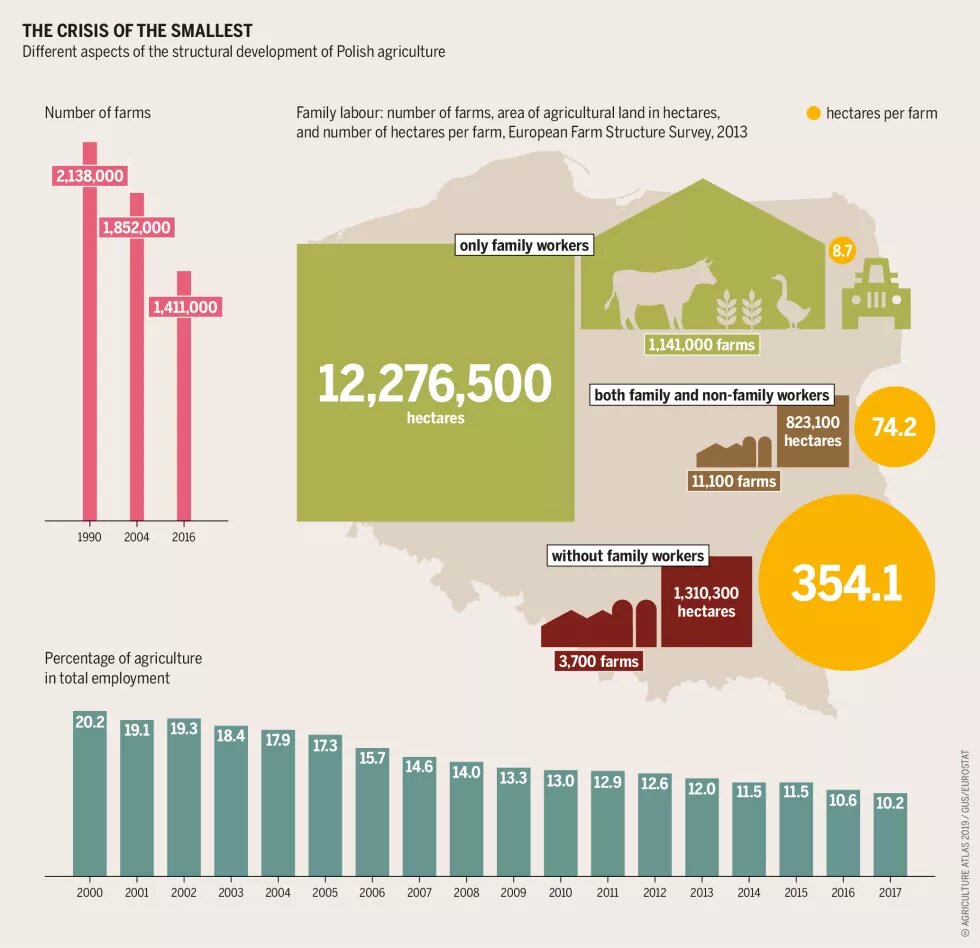

The transition from communism to a free market has resulted in both pluses and minuses for Polish farms. Incomes have risen, especially for large farms. But young people are leaving, industrial farms have appeared, small farms are going under, and the income gap among farmers has widened.

Until the mid-twentieth century, Poland was an agricultural country. In the 1950s, over half its working population were engaged in farming, and agriculture contributed almost 40 percent of the GDP. The government’s attempts to force industrialization changed the situation only slowly. At the fall of Communism in 1989, agriculture still accounted for 26.4 percent of jobs and 12.8 percent of GDP: three times the rates in developed countries. Unlike farmers in some other Soviet-bloc countries, Poland’s farmers had not been expropriated. But their farms were ill equipped and inefficient, and had seldom adopted modern production methods.

The opening of the Polish market to foreign products after 1989, along with rampant inflation, created a severe crisis. The country’s farmers could not compete with producers from the West, and no effective institutions existed to boost the export of their crops. Consumers found attractively packaged and marketed food from abroad more appealing. Agricultural production fell and became even less efficient.

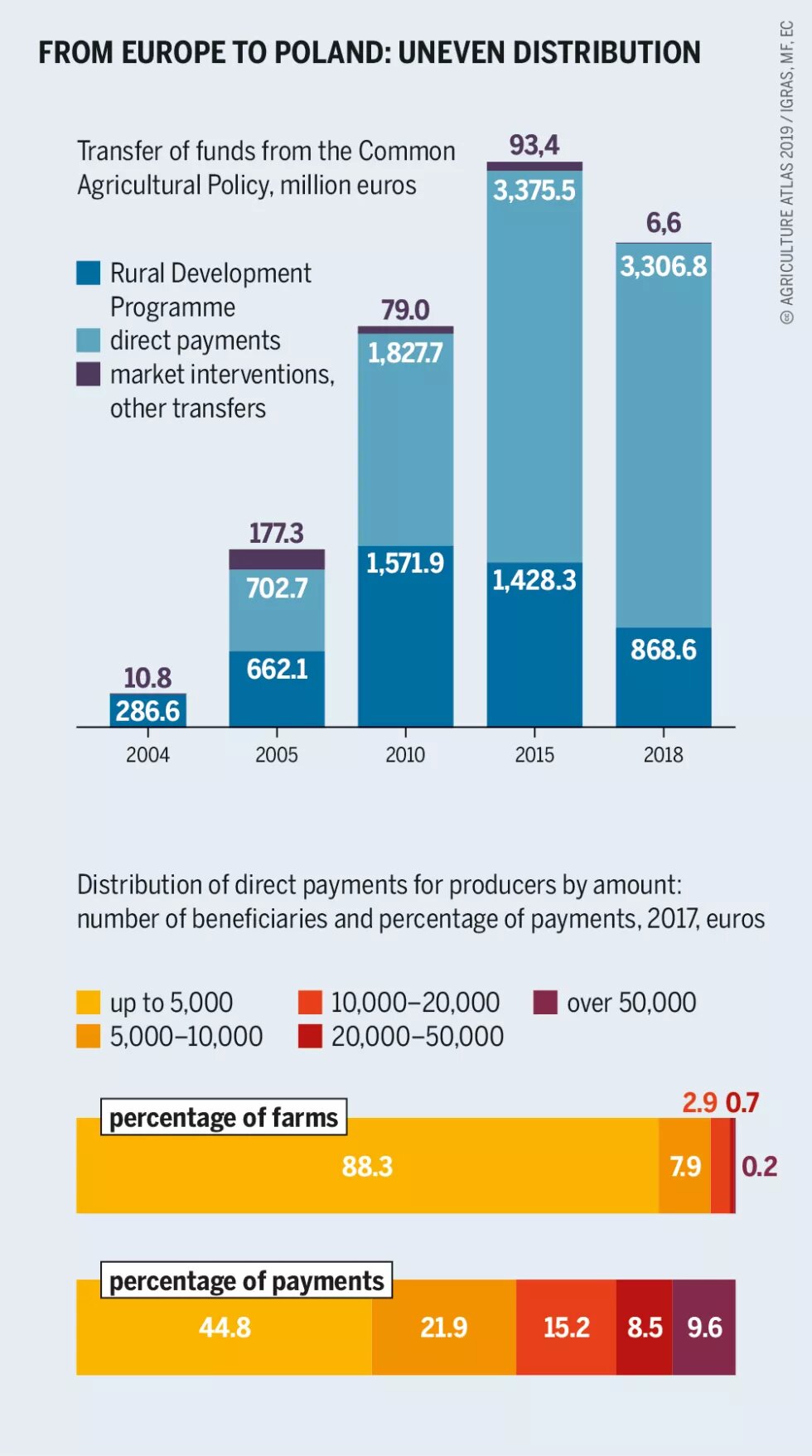

A crisis was prevented following Poland’s accession to the EU in 2004, when it gained access to European funds. Just one year later, the amount of money spent on supporting agriculture had more than quadrupled. Five years later, it was almost 15 times more. The improvement in the economic situation in the countryside is one of the most important success stories of the transformation. The percentage of people living in extreme poverty fell from over 18 to 7.3 percent in 2017, while per-capita income in rural areas rose by 118 percent, more than in urban areas (94 percent).

But success has taken its toll. Twenty-five years later, one farm in three has ceased to exist, and rural areas face depopulation: young people are abandoning the countryside in droves. Poland was the only EU country to reallocate the maximum amount (25 percent) of funds within the second pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy (dedicated to the modernization and development of rural areas) to direct payments. As a result, the biggest farms received most of the funds, and were able to invest in modernizing their production. Smaller farms did not get enough money to make these improvements; for them, the payments served more as social support.

In 2017, the biggest 20 percent of farms received the lion’s share – 74 percent – of the direct (area) payments. The remaining four-fifths of farms had to be content with a little more than one-quarter of the funds. The focus on area payments meant less money was available for agri-environmental programmes or to support sustainable rural development. As a result, the EU funds had only a modest effect on reducing inequalities between farms in different regions. The income disparities between farmers increased significantly.

Poland’s farms now fall into three categories. About 20 percent of farms are big producers that sell all their output. Within this category, some farms use highly intensive production methods. They sow large-scale crop monocultures, use huge amounts of mineral fertilizers and pesticides, and simplify the rotation of crops. This has an enormous impact on the environment: it degrades the soil and landscape, reduces biodiversity, as well as polluting groundwater and surface water. Industrial animal-raising methods such as caged production or year-round confinement cause suffering to animals. These methods also produce huge amounts of slurry, contaminating water and soil.

Industrial agriculture also inhibits the development of rural areas, leading to depopulation. Because farmers who have for years applied traditional crop and animal production methods are no longer able to compete with big farms, they give up farming altogether.

At the other end of the scale, the smallest farms maintain the land in good condition but produce either nothing (about 15 percent of farms) or as much they need for their personal consumption (about 10 percent). Many have been forced out of the market by the growing competitiveness of large farms.

The third category is also the largest; it includes over half of all Polish farms. These farms are trying to survive through commercial production but are too small to benefit from economies of scale. As a result, they seek a competitive edge by specializing or by cutting costs – for example, by simplifying crop rotations or reducing liming and the use of organic fertilizers. Such practices are important to maintain the environment. A major challenge for agricultural policy is to preserve these farms and ensure that they can produce food in accordance with good agricultural practices. The farmers who manage these enterprises are crucial for the sustainable development of rural areas. By maintaining land in good condition and by producing food less intensively than big farms, they have a positive impact on the environment, preserve biological and landscape diversity and counteract the depopulation of rural areas.