Land degradation has numerous invisible costs – environmental, health, social, and economic. True Cost Accounting renders these costs visible, offering a clearer picture of the impact of land degradation.

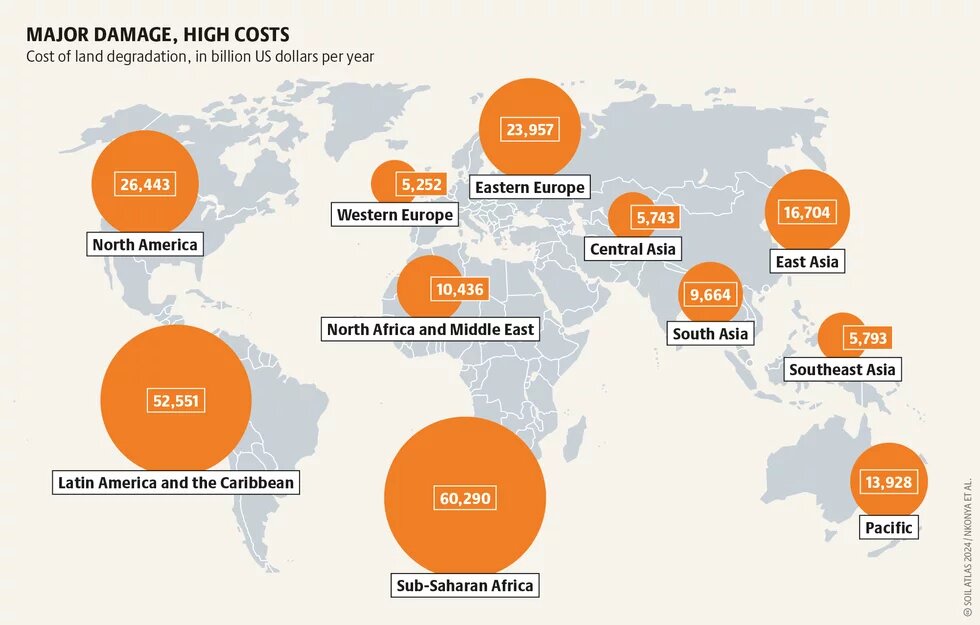

Every continent on Earth is affected by human-induced land degradation. The global cost of lost ecosystem services, for example due to desertification and land degradation, may be as high as US 10.6 trillion dollars per year. These ecosystem services include water filtration and retention, flood regulation, nutrient cycling, and waste decomposition. Land degradation can also have serious knock-on effects on human health, since it reduces food production and dries up water sources, which lead to food insecurity and malnutrition. In the European Union (EU), where land degradation affects 61 to 73 percent of agricultural soils, almost 3 million tonnes of wheat and 600,000 tonnes of maize are lost every year due to erosion alone. Degradation can also restrict access to clean water, resulting in the spread of water- and food-borne diseases.

Furthermore, land degradation exacerbates social inequalities, as it disproportionately affects rural, land-dependent households in low- and middle-income countries. The situation is particularly alarming in Africa, where about 65 percent of productive land is already degraded. In the Central African Republic, for instance, where 71 percent of the population works in agriculture, the average losses due to land degradation are equivalent to 40 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Asia and Africa bear the highest costs of land degradation, estimated at US 84 billion dollars and US 65 billion dollars per year respectively.

Conventional metrics for economic performance – such as GDP and earnings – fail to take account of the long-term consequences and hidden costs of land degradation. This is a fundamental flaw of the current economic system, where corporations are able to privatise profits but leave societies and future generations to bear the environmental costs. This distorts economic signals and decision-making and incentivises practices that prioritise short-term gains at the expense of long-term planetary and human health.

One way to address this issue is to incorporate the full costs of land degradation and the true value of sustainable land management into macroeconomic analyses and corporate accounting and reporting. This approach is called True Cost Accounting (TCA). Businesses, policymakers, and other stakeholders in the food system can use TCA to measure, monetise and disclose the full costs and benefits of corporate practices. In the case of land management, this means calculating the environmental, health, social, and economic costs of land degradation, and putting a value on the benefits of sustainable land management. One study that assessed the hidden costs and benefits of maize production in Zambia found that common agricultural practices cause the loss of up to 16 tonnes of topsoil per hectare each year through erosion. The externalised environmental costs are 2 to 2.5 times higher than what it currently costs farmers to produce maize. But if farmers adopt more sustainable farming practices, small-scale mixed cropping can reduce environmental costs to almost zero.

TCA reveals the benefits of investing in sustainable practices, thereby encouraging investments in sustainable transitions. Calculations that value ecosystem services and ecological restoration show that restoration projects not only slow down biodiversity loss and absorb carbon dioxide but are also economically viable. On average, the benefits of restoring degraded land are ten times greater than the costs of restoration.

By quantifying the environmental, health, social, and economic impacts of land degradation in monetary terms, TCA also makes it easier to incorporate sustainability information into financial reporting, such as balance sheets and management reports. This allows sustainability-related values to be viewed on an equal footing with other economic values, and the results can be used to hold businesses accountable. For example, in its 2022 annual report, Olam, an international agrifood corporation, published a natural capital profit-and-loss statement for ten selected farmer groups and processing facilities, quantifying their positive and negative impacts on climate and water.

For TCA to become an effective accounting and reporting tool and transform the way companies operate, it needs to be complemented by additional policy measures, such as linking executive bonuses, dividends, taxes, and subsidies to a company’s sustainability performance. The current voluntary nature of TCA allows those who cause the most external costs, particularly unsustainable companies, to avoid transparency and accountability. Further necessities include standardising TCA methods to support more efficient implementation and consistent comparison of assessments. But even without such improvements, TCA can be used today to identify the hidden costs and benefits of land degradation and sustainable land management practices. As the first pilot projects have shown, these calculations can inform policy and business considerations, thereby helping to solve the problem of land degradation.