Digital trust is a trojan horse. For years, LinkedIn has maintained its position as the most trusted digital platform globally. Yet this same trust may be its greatest vulnerability. When we feel safe, our defences drop. And misinformation thrives in these unguarded moments.

LinkedIn stands apart in the social media landscape. The platform ranks among the oldest major social networks, predating Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. It has grown into one of the largest digital platforms globally, with over a billion registered users and nearly a third engaging monthly. But LinkedIn's significance stems from more than just its age or scale. The platform functions as the premier space where professionals across industries share ideas and engage in critical discussions - from policy and technology to innovation and climate action. Yet, despite this massive reach and influence, it has largely escaped the scrutiny that other large social platforms like Facebook and Twitter have faced in misinformation studies.

This absence of scrutiny might stem from a simple reason: people trust LinkedIn. Unlike other platforms infamous for chaotic feeds and anonymous accounts, LinkedIn’s professional identity lends it an automatic credibility. Its architecture—the visible job titles, work histories, and affiliations—primes users to perceive it as a reliable space. When content comes from sources with apparent professional authority—whether it’s an industry executive or a technical expert—it’s often accepted at face value, subject to far less scrutiny.

This implicit trust creates a dangerous vulnerability. While users have developed healthy scepticism toward content on platforms like Facebook and others, LinkedIn's professional context signals legitimacy by default. We expect what we see on LinkedIn to be credible because it is shared by a seemingly credible source. We trust what we see because of where we see it.

But blind trust creates blind spots. We don't expect to encounter misinformation on LinkedIn, making it easier for false or misleading content to proliferate unchallenged. This high trust and low scepticism led Ripple Research to ask a crucial question: Is misinformation present on LinkedIn, and if so, what forms does it take?

This question becomes particularly urgent in the context of climate misinformation. While misinformation pervades many areas—from public health to elections—none carry the same existential weight as climate change. Misleading narratives that question climate science or undermine climate solutions can have cascading effects across society. Delays in climate action, driven by resistance rooted in confusion or manufactured doubt come with rising costs and shrinking opportunities to act. Ensuring that discourse on climate innovation and action remains grounded in facts is crucial to preventing the derailment of necessary solutions. Recognising this critical need, Ripple Research launched a first-of-its kind investigation into climate misinformation on LinkedIn.

How we conducted the study

Our study was designed as an initial exploration to develop insights into LinkedIn’s climate misinformation landscape. However, we had to navigate the platform’s unique research constraints. Unlike API-accessible platforms such as Twitter, where data scraping can be automated, LinkedIn’s terms of service prohibit automated data collection methods, including scraping and crawling. This meant that every post, every piece of data had to be collected manually.

Rather than seeing this as a limitation, we turned it into an opportunity for students to develop hands-on digital literacy skills, partnering with Prof. Gunnar Schade at Texas A&M University. As a part of the ATMO 444-500 course, students were tasked with manually reviewing thousands of LinkedIn posts about climate change, identifying misinformation and categorising it into predefined buckets.

The project had 3 building blocks

1. A foundation of information: The project began with introducing students to the concept of analysing climate change misinformation, including through examples of misleading narratives found on LinkedIn. Students referred to an existing framework—CARDS (Computer-Assisted Recognition of Denial and Skepticism)—to guide the analysis. CARDS was developed by researchers at the University of Exeter, Trinity College Dublin, and Monash University to enable the systematic identification and classification of climate misinformation at scale. CARDS segments climate misinformation into five primary categories, encompassing everything from outright denial of climate change to more subtle tactics like undermining climate solutions or climate science. Clear guidelines on applying the CARDS framework were provided, ensuring students could systematically categorise misinformation.

2. A platform to collect the data: To manually capture this volume of data systematically, we created a bespoke platform that gave students a clear framework for their research. The tool helped maintain consistency in how students documented their findings, and contained fields such as:

- Post content and author profiles

- Publication dates and relevant hashtags

- Engagement metrics (likes, shares, comments)

3. The manual review & analysis of climate change posts: Students meticulously reviewed thousands of posts about climate change on LinkedIn, isolating instances of climate disinformation, and logging key details and categorising content based on CARDS classifications. This process required careful attention to narrative framing, source credibility, and engagement levels.

Key insights from the study

After multiple rounds of review and validation, we arrived at a final dataset of 1,388 unique misinformation posts with a total engagement of 245,000 interactions (likes, shares, and comments). We analysed this data and found several key patterns:

1. Dominant Narratives: Undermining Solutions and Science

The two most common narratives in our dataset were:

- “Climate solutions won’t work” (32% of posts): Within this category, a majority of posts focused on how clean energy would not work, and how climate policies are harmful.

- “Climate science/movement is unreliable” (30% of posts): Here, posts found disparaged both climate science and the climate movement.

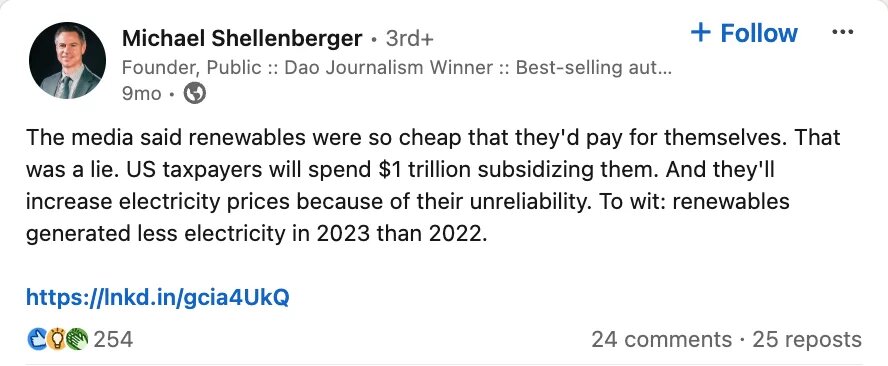

Narratives in posts found rarely denied climate change outright. Instead, they employed more sophisticated tactics, focusing on eroding trust in climate solutions and scientific consensus. Posts often framed renewable energy as ineffective, expensive, or impractical, using misleading statistics or cherry-picked anecdotes. Others worked to undermine climate science by portraying it as uncertain or politically motivated.

2. High Engagement with Misinformation

Categories with the highest volume of posts also garnered the highest engagement. Posts questioning climate solutions and the reliability of climate science accounted for a combined 63% of total engagement.

3. The Role of “Misinfluencers”

Our author analysis showed that a small group of users—whom we termed “misinfluencers”—played a disproportionate role in spreading misinformation. The top 5% of authors in our dataset were responsible for 39% of posts and attracted a substantial portion of active engagement. Their posts were responsible for 46% of comments and 44% of reshares. These individuals often had large followings and professional credentials, giving their posts an air of legitimacy despite spreading misleading narratives.

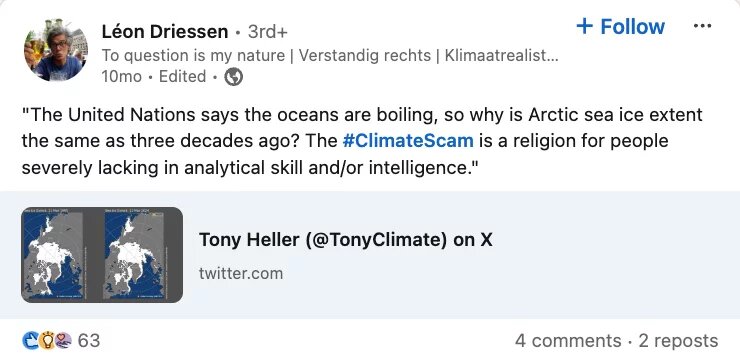

4. Hashtag Patterns

We also identified patterns in the use of hashtags. Well-known denial hashtags like #climatescam and #climatehoax appeared frequently, alongside others that downplayed the severity of the climate crisis. Interestingly, hashtags like #catastrophizing were used to frame legitimate climate concerns as exaggerated or alarmist, further contributing to a narrative of doubt.

Sensemaking

Our research reveals a sobering reality– that no digital platform, not even the most trusted ones, can be entirely misinfo-proofed. Even LinkedIn has become a channel for climate misinformation. What this signals to us is that regardless of design or reputation – platforms aren’t inherently immune to the spread of misleading narratives.

We also know that platform level protections against such misleading narratives have been unreliable at best, and non-existent at worst. This only seems to be getting worse as the trust infrastructures of our digital town squares are being taken apart piece by piece. Twitter is a notable example - in late 2022, its new ownership fired approximately 3,000 content moderators overnight and proceeded to methodically dismantle its fact-checking infrastructure. Meta followed a similar path that same year by laying off significant portions of its trust and safety teams. Now in 2025, Meta has stripped away its fact-checking program in the US, a move that impacts Facebook, Instagram and Threads – particularly notable since Threads had been positioned specifically as a safer, more protected alternative to a destabilised Twitter. These changes leave users exposed to unchecked information flows, with vital spaces for public discourse transformed overnight. The speed of these changes leaves communities no time to adapt as more layers of protection fall away.

This reality demands a shift in how we think about fighting misinformation. At Ripple Research, we believe that instead of primarily focusing on sanitizing or misinfo-proofing information ecosystems — a pursuit that, while necessary, struggles to keep up with the ever-evolving ways misinformation mutates and proliferates online — we must focus more on misinfo-proofing people. This means equipping individuals with the skills to critically evaluate content, regardless of where they encounter it. While platform-level safeguards remain crucial and must be defended, recent events make clear why building human capacity for information discernment is absolutely vital. We need approaches that endure even as our digital spaces transform around us.

One way to cultivate this capacity is through hands-on media literacy training – our collaboration with Texas A&M University demonstrates what such an approach can look like in practice. Similar models can be adapted and implemented across various settings - universities, workplaces, and community settings - developing a public better prepared to evaluate information critically, regardless of where they encounter it or how trusted the space may seem.

The views and opinions in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union.