Three percent of the world’s peatlands have been destroyed for forestry purposes, releasing large quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Drained peat soils are the scene of devastating fires that are used to clear land.

Around the world, some 15 million hectares of peatlands have been drained to make way for plantations or forestry. Often enough the term forestry also means the monocultural cultivation of trees such as pines in plantations. When we refer to peatlands and forests, three drainage-based land use changes can be distinguished: the drainage of already forested mires, the drainage of open, rather treeless peatlands for afforestation, which mostly occurs in the nordic countries, and the drainage of naturally forested peat swamp forests in the tropics for the establishment of plantations after clearcutting the original forest. All can be conducted by large enterprises but also by smallholders, facilitated by the industrialization of forestry and agriculture.

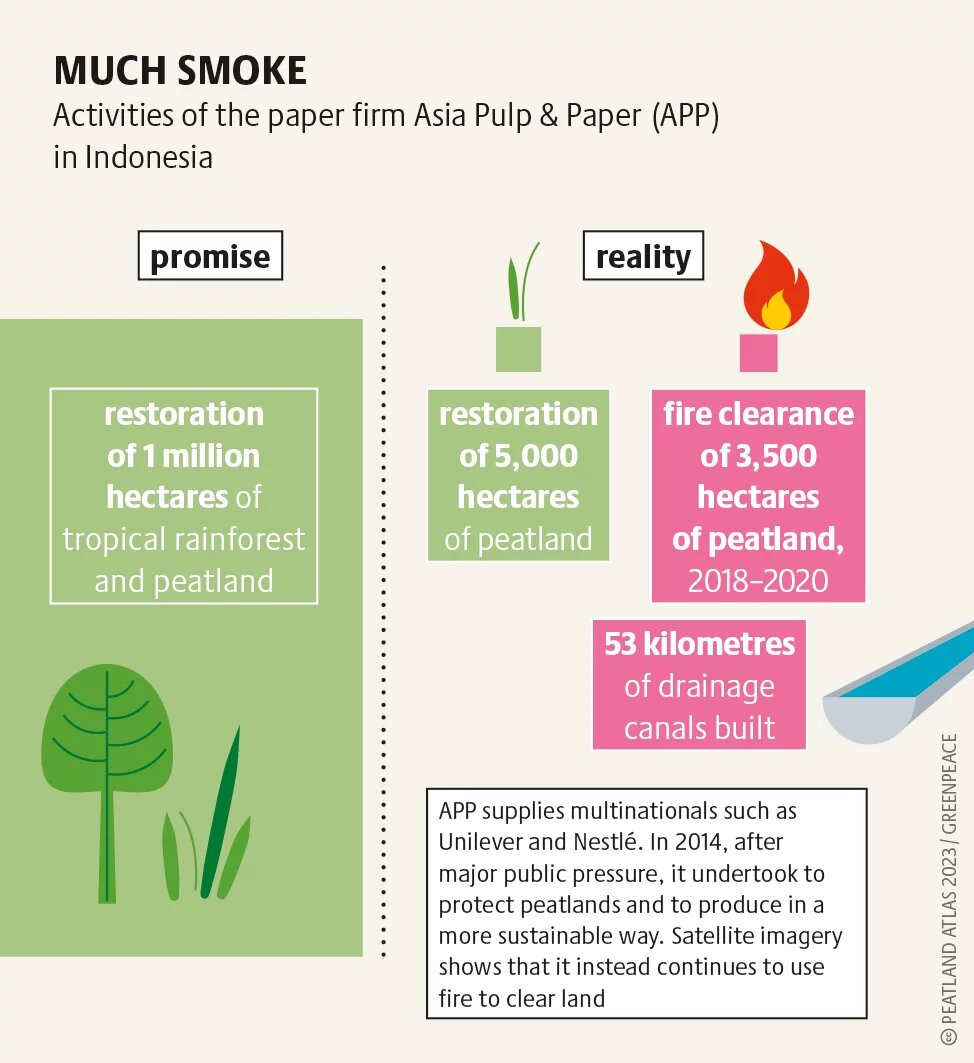

Drainage for intensive, even industrialized land use always leads to a decline in biodiversity. In dense tree plantations, hardly anything can grow on the ground or in the undergrowth. In Europe, the largest areas of peatlands that have been drained for forestry are found in Finland and Russia, where they cover an area of 6.6 million hectares. One-third of Finland’s forests are on peat soils, making peat-forest management very important for the country’s economy. Since the middle of the last century, Finland has drained more than half of its peatlands – though the government is now making effort to restore them by reversing the drainage. In the tropics, drainage of peat swamp forests accelerated during the past decades due to an increasing global demand for tropical crops, timber and pulp wood such as from palm oil or acacia. Especially Southeast Asia has been a hotspot of peatland drainage, but also other tropical peatland forests are currently under threat as the need for arable land and forestry increases.

The dilemma of forestry on drained peatlands is that newly planted trees sequester carbon, but at the same time the drained soils release vast amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The decomposing peat emits carbon dioxide (CO₂), while the drainage ditches and canals release methane. Emissions of nitrous oxide may also rise, especially if fertilizer is applied. Drained organic soils are also susceptible to forest and peat fires. Large, long-lasting peat fires occur in the high-latitude parts of Canada and Eurasia, as well as in tropical areas and pose an additional great threat to the climate. Furthermore, these fires produce large amounts of toxic smoke that can be deadly for people and animals.

To prevent fires from raging each year and causing loss of biodiversity, significant health issues, massive emissions, widespread destruction and loss of life, it is necessary to maintain and restore moisture levels in peat soils. Rewetted peatland forests provide good conditions for sustainable forestry. Society can benefit in many ways from the climate effect of wet peatland forest, if on the one hand the carbon remains bound in the peat, and on the other hand additional carbon is sequestered in long-lasting timber products. Like other wetlands, peatland forests also act as local cooling: shade and respiration by the natural vegetation create a microclimate with cooler temperatures and fresh air.

In temperate climates, black alder can grow in areas with high water tables. Its average rotation length – the time from planting to harvest of a stand – is between 60 and 80 years. The wood of the black alder is suitable for special construction purposes and is cheaper than oak or birch. Still, the profitability of such forests is low because of the trees’ growth forms as well as their harvest is difficult on soft, wet peat soils, in regions where these soils do not freeze.

A similar problem occurs in tropical peatland forests. There, some large individual trees are so valuable that it is economically profitable to harvest only them, leaving the surrounding trees standing. However, dense stands of other trees and soft ground make it difficult to use machinery.

Often, trees are felled illegally, with individual logs being floated down narrow, hand-dug canals. These uncontrolled channels can lead to the lowering of the water table and the gradual degradation of the peat swamp forest, causing emissions and subsidence. To limit both uncontrolled and intended drainage, policies, social and financial incentives, as well as monitoring and law enforcement are needed to manage the land sustainably. Paludiculture, the cultivation of plants adapted to wet peatland environments, and sustainable peat swamp fisheries can combine the preservation of ecosystem services with production of food, feed, fuel, fibre and other goods.

Already in 2002, the International Mire Conservation Group and the International Peatland Society, proposed a framework for the Wise Use of peatlands. In 2014, the Food and Agiculture Organization of the UN (FAO) has published the report Towards climate-responsible peatlands management. It also highlights the need for capacity development and information dissemination, community engagement, and good governance.