The green turn in central banking has generated considerable controversy. Some voices have questioned central banks’ growing engagement with climate issues, arguing that unaccountable technocrats do not have the tools or the political legitimacy to intervene in (or possibly highjack) the low-carbon transition. Others question the continued emphasis on voluntary decarbonisation, even among green champions in the central bank community. This paper intervenes in and nuances this “too little vs too much” debate.

The green turn in central banking has generated considerable controversy. At one end of the spectrum, the “central banks are doing too much” voices have questioned central banks’ growing engagement with climate issues, arguing that unaccountable technocrats do not have the tools or the political legitimacy to intervene in (or possibly highjack) the low-carbon transition. Instead, this process should be guided by political commitments to higher carbon taxes, the fiscal de-risking of green private investment, and where fiscal space permits it, green public investment.

At the other end, the “central banks are doing too little” camp questions the continued emphasis on voluntary decarbonisation, even among green champions in the central bank community (Bank of England, the European Central Bank, ECB). It points to the systemic greenwashing that characterises private credit creation to argue that central banks need to urgently create frameworks for the rapid and mandatory decarbonisation of private finance.

This paper intervenes in and nuances the “too little vs too much” debate. It first unpacks the climate question(s) for central banks, to then argue that the pace and nature of decarbonisation – the build-up of green productive capacities and green infrastructure – is ultimately a question of the broader institutional context that configures the relationship between central banks, private finance, and fiscal/industrial authorities.[1] Put differently, the status-quo monetary dominance arrangement that characterises financial capitalism – where inflation-targeting policies play the decisive role – cannot generate the institutional basis for a green “nationalisation of credit[2] that systematically directs credit towards green productive capacities. Instead, this central bank-dominated arrangement delegates the specific pace and nature of the structural transformation to private finance – with the attendant risks of greenwashing – and is vulnerable to a “price stability first” central bank mandate.

1. The climate policy question: (Mandatory) decarbonisation for financial/monetary stability vs green structural transformation

For most central banks, the climate question is how to decarbonise the financial system for financial or monetary stability purposes. Central banks can interpret this policy question in two ways, either as a) how to reduce climate risks, including transition risks from carbon tax policies, to private finance’s balance sheets (single materiality, a la ECB), or b) how to reduce both climate risks and the climate footprint of private finance (double materiality, a la Bank of England).

The Network for Greening the Financial System, a worldwide network of central banks, is guided by the financial/monetary stability framing precisely because this organises, and legitimises, monetary decarbonisation efforts within the institutional set-up of monetary dominance, defined by central banks[3] as operational independence to pursue inflation targets with no formal requirement to stabilise the costs of government borrowing (known as fiscal dominance) or to intervene directly in the private allocation of credit. To preserve their claims to independence and defend their hegemonic position in the macrofinancial status quo, inflation-targeting central banks argue that they have a legitimate stake in fighting the climate crisis by construing it as a direct threat to price or financial stability.

In contrast, a handful of central banks, mostly in middle- or low-income countries, have promoted or announced initiatives to encourage (small-scale) green private lending to green sectors, with the aim of accelerating the low-carbon structural transformation. When green monetary policy explicitly targets structural transformation, it is often designed in coordination with green industrial policies.[4]

2. Mandatory decarbonisation under monetary dominance: Soft credit guidance

Some central banks are accelerating the move to mandatory decarbonisation, understood as adjustments to monetary and regulatory frameworks that are designed to green monetary/regulatory policies, including collateral policies and unconventional bond purchases.

The first step, typically taken in context of unconventional corporate bond purchases, was for central banks to accept that the principle of market neutrality hardwires a carbon bias[5] in monetary policy operations. Market neutrality allows central banks to eschew accusations of intervening in the private allocation of credit – it instructs central banks to organise unconventional purchases of corporate bonds according to the bond market share of the corporate issuer. In so doing, central banks implicitly disregard the fact that carbon-intensive issuers are overrepresented in the bond markets because markets misprice climate risks.[6] But we should not overestimate the importance of this shift in the world of central banks. The acknowledgment of carbon bias does not imply, or indeed require, a fundamental shift away from the current regime of monetary dominance. Nor does it require a fundamental structural transformation of financial capitalism, understood as entrenched infra/structural power[7] of private finance, as it can be deployed to secure state protection (or de-risking) for systemic liabilities and new asset classes such as green/infrastructure/nature assets.[8]

When the topic of carbon bias is considered, the principle of market neutrality is a fiction, albeit a politically powerful one. It is a fiction in the sense that “following the market” in practice means that central banks subsidise carbon issuers (say Shell) when purchasing corporate bonds, since the market fails to price climate risks. The Trojan horse of market neutrality hides carbon subsidies.

Yet paradoxically, central banks have been reluctant to abandon market neutrality altogether, a political decision to preserve the appearance of independence against (conservative) charges that greening monetary/regulatory policies means green interventionist credit policies. Take the Bank of England, the first with an explicit environmental mandate among high-income countries, and thus an interesting case study in the new political economy of mandatory decarbonisation. It first announced plans to green the corporate bond purchase programme by tilting reinvestments within but not across sectors in November 2021. This would have retained market neutrality and, in practice, could have perversely led the Bank to offer better treatment to carbon-intensive companies than to green companies.[9] It then abandoned its greening plans altogether in February 2022, announcing that it would liquidate its portfolio of corporate bonds by the end of 2023 – a decision motivated by the imperative of shrinking its balance sheet (or quantitative tightening) to contain widespread inflationary pressures. Put differently, the Bank subordinated its environmental mandate to its (interpretation of) of the price stability mandate, and sacrificed its experiments with decarbonising unconventional monetary policy tools on the altar of price stability. It need not have done so, since the Bank can tighten monetary conditions without having to liquidate its corporate bond holding.

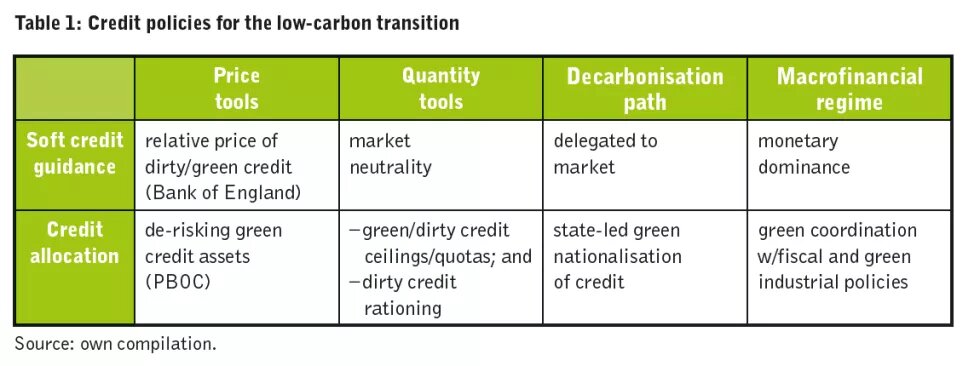

The Bank of England’s example suggests that even at its most ambitious, mandatory decarbonisation under monetary dominance amounts to soft credit guidance[10]: It aims to increase the relative price of dirty credit created on bank balance sheets or in bond markets via signalling effects and demand effects. When central banks signal to private markets their views about green vs dirty assets, the effect is potentially more influential than changes in central bank demand for green/dirty bonds, since their corporate bond portfolios and collateral portfolios are relatively small (see Table 1). But central banks do not set new green/dirty asset prices (via haircuts on collateral or directly) based on a strategy of promoting certain green activities or industries. Signalling (central bank views of dirty vs green asset prices) and demand (changes in demand for assets from tilting or central bank divestment) effects do not per se guarantee that private finance redirects credit flows into green productive activities, as opposed to asset bubbles in property or other new asset classes.

Under monetary dominance, central banks do not target a sector-specific price of credit or quantity of credit, and their climate frameworks aim at the general greening of both monetary/regulatory policies and the financial system without seeking to promote any distinctive low-carbonisation pathway.

The Bank of England’s commitment to market neutrality discussed above illustrates well the vulnerabilities of a strategy that outsources the greening pathway to markets. Where monetary decarbonisation and price stability appear to be at odds with each other, inflation-targeting central banks will inevitably prioritise the latter. Furthermore, the climate costs of this strategy can be significant, considering the systemic greenwashing that prevails in private finance.

In the absence of specific mechanisms of coordination with green industrial policies, mandatory decarbonisation through green central banking delegates the specific pace and nature of structural transformation to private finance.

3. Monetary policy aimed at the structural transformation of economic activities: Credit allocation

Credit allocation policies go further than credit guidance in that these are set within an overall explicit strategy – coordinated with fiscal and industrial policies – to closely steer the structural transformation of the economy. Monetary dominance is replaced with a macrofinancial regime of closer green coordination between credit, industrial, and fiscal policies, and with policies aimed specifically at rationing the access to credit for high-carbon activities.

Such structural monetary policies have historically relied on quantitative tools – credit ceilings and quotas targeting level/growth rate of credit in certain sectors, or “window guidance” allocation to banks and industrial sectors in line with nominal GDP growth targets or strategic aims.[11] This green nationalisation of credit would have to go hand in hand with dirty credit rationing to reduce access to new credit for dirty activities.

However, so far even the more ambitious central banks have preferred price-based green credit allocation. The People’s Bank Of China, the central bank of China, introduced a new “carbon emissions reduction facility” (CERF) in 2021, through which it encourages banks to lend to a set of priority green sectors that specialise in developing and adopting clean energies, improving energy efficiency, and adopting decarbonisation technologies.[12]

But the design of the CERF tool is more market-based than traditional quantitative tools: The PBOC would provide banks with reserves on preferential terms (60% of qualifying loans at an interest rate of 1.75% with a one-year maturity, to be rolled at most twice), expecting that banks would in turn create green loans at rates close to the one year PBOC rate. Similarly, the Bank of Japan announced in December 2021 an $18 billion green financing scheme through which it provides zero interest rate loans to banks for a two year period that can be extended to 2030. Compare this with the Term Funding Scheme of the Bank of England, which had the specific aim of passing the low policy rates onto households and businesses.[13] The Bank of England only agreed to lower funding costs for UK banks if these passed those onto households and businesses, imposing a tighter conditionality on banks than either the Chinese or the Japanese central banks.

These price-based green refinancing tools fall under the broader umbrella of green TLTROs[14] recently proposed for the ECB. Central banks offer banks long-term refinancing operations against green (loans/bonds) collateral, thus effectively encouraging the banking system to finance their green credit assets with cheaper green public funding.

The logic of lending against green collateral is inherently one of credit allocation, as the central bank identifies a set of sectors for which it supports private green credit creation. The sectoral criteria can be guided by an industrial policy strategy (as appears to be the case of the PBOC) or by green taxonomies, such as the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance taxonomy. It can involve judgments about the greenness of the underlying assets if the taxonomy applied has been designed by other private or public actors, since these can be subject to greenwashing (as is arguably the case for the European Sustainable Finance taxonomy).

Perhaps more important, in the absence of specific sectoral-level quantity targets, the green refinancing logic remains one of de-risking private green credit creation also built within the soft credit guidance discussed above. The purpose is to change the risk/return profile of private green credit assets in the expectation that such price incentives would generate supply responses from the banking or shadow banking systems[15] and higher demand for credit from green sectors. It is indeed stronger than the soft credit guidance discussed above, but its effectiveness in generating a rapid structural transformation of the economy is again contingent on private shadow/banking decisions.

Questions to resolve for the credit allocation pathway

Whatever the combination of quantitative and price tools, the credit allocation pathway requires (scholars of) central banks to address several broader political economy questions about green transformations under financial capitalism:

- Does the green transformation of productive structures require the transformation and/or shrinking of private finance in its market-based stage, given its demonstrated propensity to greenwashing and its resistance to the necessary stranding of fossil fuel assets? Can this be achieved via dirty credit rationing alone, or does it require green financial repression?

- Since decarbonisation requires the destruction of financial wealth generated by fossil fuel assets (such as oil and gas), what should be the role of central banks in the institutional set-up that will organise the management of stranded assets?

- Since carbon assets are largely issued and managed on globalised balance sheets (of institutional capital, including asset managers and private equity, and global banks), what would a global framework for both penalising new dirty credit and for preventing “brown-spinning” – that is, the transfer of carbon assets to private equity funds that have little regulatory scrutiny – look like?

[1] As elaborated in Carolyn Sissoko’s contribution in this series. Braun and Gabor theorise these as macrofinancial regimes, understood as institutional modes of creation and access to financial assets, including money; see B. Braun and D. Gabor (2022), In Search of a Green Macrofinancial Regime, mimeo.

[2] See E. Monnet (2018), Controlling Credit: Central Banking and the Planned Economy in Post-war France, 1948-1973 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

[3] See, for instance, I. Schnable (2020), The Shadow of Fiscal Dominance: Misconceptions, Perceptions and Perspectives, European Central Bank, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200911~ea32bd8bb3.en.html.

[4] For an elaboration, see B. Allan, J. I. Lewis, and T. Oatley (2021), “Green Industrial Policy and the Global Transformation of Climate Politics”, Global Environmental Politics 21(4): 1-19.

[5] See L. Boneva, G. Ferrucci, and F. P. Mongelli (2021), To Be or Not to Be “Green”: How Can Monetary Policy React to Climate Change? https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op285~be7d631055.en.pdf?ddcbc43ab00d4c7a96e9d27aaa972748.

[6] See Y. Dafermos, D. Gabor, M. Nikolaidi, A. Pawloff, and F. van Lerven (2021), Greening the Eurosystem Collateral Framework: How to Decarbonise the ECB’s Monetary Policy, https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/35503/1/Dafermos%20et%20al%20%282021%29%20Greening%20the%20Eurosystem%20collateral.pdf.

[7] See B. Braun (2020), “Central Banking and the Infrastructural Power of Finance: The Case of ECB Support for Repo and Securitization Markets”, Socio-Economic Review 18(2): 395-418; see also B. Braun (2021), From Exit to Control: The Structural Power of Finance under Asset Manager Capitalism, https://uni-frankfurt.zoom.us/j/94043210548?pwd=cmRzODBVRGhwMHlhUmlwT1BLZUpNdz09.

[8] see D. Gabor (2020), “Critical Macro-finance: A Theoretical Lens”, Finance and Society 6(1): 45-55.

[9] See Y. Dafermos, D. Gabor, M. Nikolaidi, and F. van Lerven (2021), An Environmental Mandate, Now What? Options for Greening the Bank of England’s Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (SOAS Working Paper no 22), London: SOAS University of London.

[10] For an elaboration, see J. Ryan-Collins, D. Gabor, and K. Kedward (2022), Green Credit for the Low-carbon Transition, mimeo.

[11] See D. Bezemer, J. Ryan-Collins, F. van Lerven, and L. Zhang (2021), “Credit Policy and the ‘Debt Shift’ in Advanced Economies”, Socio-Economic Review, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwab041.

[12] See ‘PBOC Officials Answer Press Questions on the Launch of Carbon Emission Reduction Facility’

http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688172/4157443/4385447/index.html

[13] See Bank of England (2018), The Term Funding Scheme: Design, Operation and Impact, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2018/term-funding-scheme-web-version.pdf.

[14] Targeted longer-term refinancing operations; see J. van ‘t Klooster and R. van Tillburg (2020), Targeting a Sustainable Recovery with Green TLTROs, http://www.positivemoney.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Green-TLTROs.pdf.

[15] For an elaboration of the growing importance of state de-risking as a new instrument of statecraft in financial capitalism, see D. Gabor (2021), “The Wall Street Consensus”, Development and Change 52(3): 429-459, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dech.12645.