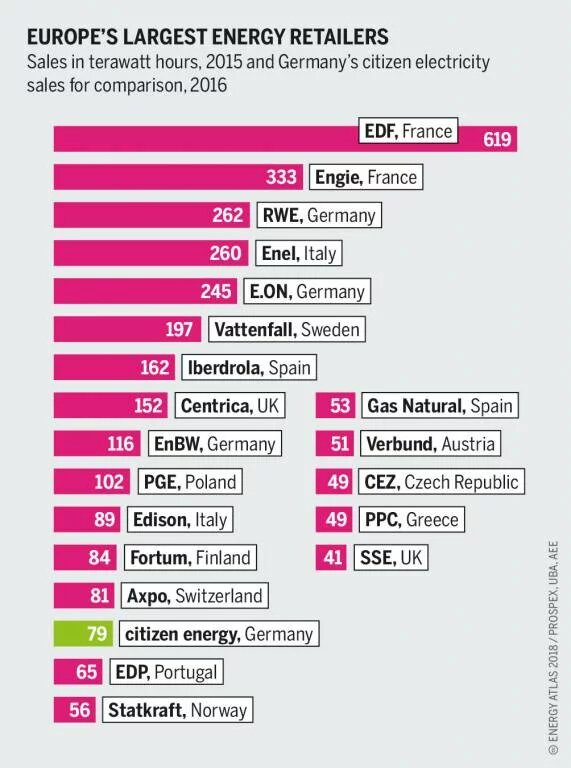

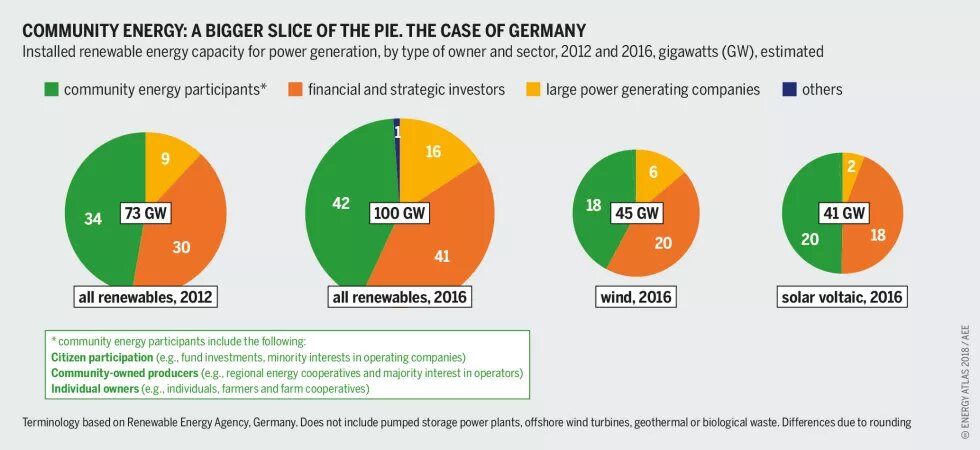

Conventional energy comes from a few large, powerful firms. But for renewable energy sources, it makes sense for the generation capacity to be owned by individuals and communities. Policies that encourage this create local support for the development of renewable infrastructure instead of opposition.

The two countries in Europe that have installed the most renewable energy since 2009 are Denmark and Germany. These are also the countries with the highest citizen participation in the energy transition. In Germany, many different ownership models exist, and only five percent of the installed renewable energy capacity is owned by large, traditional energy utilities. In Denmark, wind projects are given permits only if the developers are at least 20 percent owned by local communities.

In many countries public objections have slowed or blocked the development of renewable energy. But if citizens own, or co-own, renewable installations, they are more likely to welcome projects, and less likely to object to them. It is easy to understand why people are less keen on large infrastructure in their community when all the profits flow out of the local area and they do not have any say in where and how the project is developed. Such nimbyism has been a serious problem particularly in the United Kingdom and now also in Belgium, France and other parts of Europe. It is therefore essential to put people and communities at the heart of the Europe-wide energy transition.

Participation in local energy systems brings the Energiewende nearer to the people

The energy transition is a challenge that needs to be acted on at every level of society. The proposed Clean Energy package of 2016 is an attempt by the EU to set the goals and rules for the European energy system in the period up to 2030. But large chunks of legislation like this can seem remote and obscure. Many normal citizens see that their energy systems are owned by a few big companies, which make a lot of money, are governed by a small elite of managers in their corporate headquarters and are subject to policymakers in Brussels.

But community renewable-energy projects already exist in all shapes and forms. The cooperatives and community groups that own and run them connect the local with the European levels. When citizens own and do well out of the energy system, concepts like the European energy transition are no longer distant but have a relevance and importance to people’s lives.

Community energy neews the right political framework

There are many reasons a community may want to invest in a local energy project. Projects that are locally owned generate eight times more profit to the local economy than equivalents that are owned by transnational developers. That both helps the local economy develop and brings intangible benefits such as a sense of pride in the community.

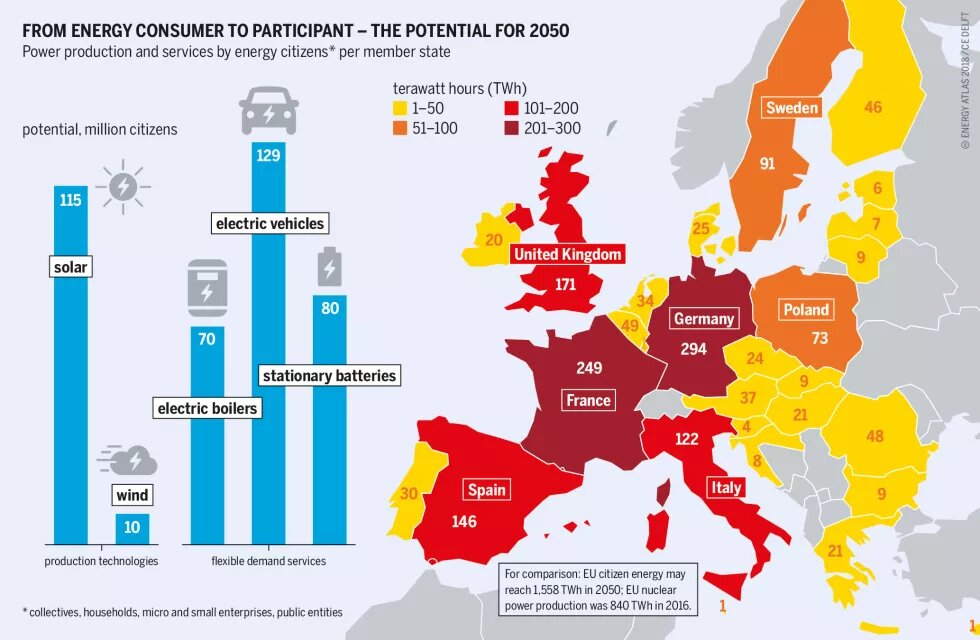

There is no central database, so it is difficult to estimate the number of citizens involved in the energy transition. But it is clear that many thousands of diverse projects exist across Europe. Eastern Europe is lagging behind as suitable policy conditions do not exist, and governments still give special treatment to fossil fuels and nuclear energy. These countries have huge potential; with the right policy framework, community energy will be able to spread eastwards.

A 2016 report by CE Delft, a research organization, estimated that 264 million “energy citizens” could generate 45 percent of the EU’s electricity needs by 2050. The same report also shows the potential of different types of energy citizens: in 2050, collective projects and cooperatives could contribute 37 percent of the electricity produced by energy citizens. These are the projects that often have the largest positive impact on the local economy.

Achieving such levels of ownership will depend on the right policies – but these are lacking in many countries. One of the biggest barriers is the current overcapacity in the energy market: the amount of electricity being generated exceeds the demand. This is because a lot of fossil and nuclear energy is being subsidized in order to maintain “energy security”, thus stifling the market for community-owned renewable projects.

Current rules make it unlikely that millions of people will participate in the energy transition in the next decade. Changes are needed, and much will depend on the decisions made in finalizing the proposals put forward in the Clean Energy package. A stable, supportive framework would mean a right for citizens and communities to produce, consume, store and sell their own energy. It would require eliminating the excess charges and administrative barriers that block community projects, as well as creating a level playing field so that they can enter the market.