For thousands of years people have taken to the sea to fish and trade. Wars have been fought as rival rulers claimed the rights to the sea and its exploitation. Those conflicts have continued to this day.

But it is no longer merely a matter of access to shipping lanes. The reason for the current international conflicts actually lies beneath the waves. The disputes revolve around the expansion of territorial seas and economic zones in order to secure exclusive rights to socalled non-living marine resources, like the valuable minerals and fossil fuels buried beneath the sea floor. They are about “territory” in the sea. Absurd? Not if you look at where land begins. And where it allegedly ends.

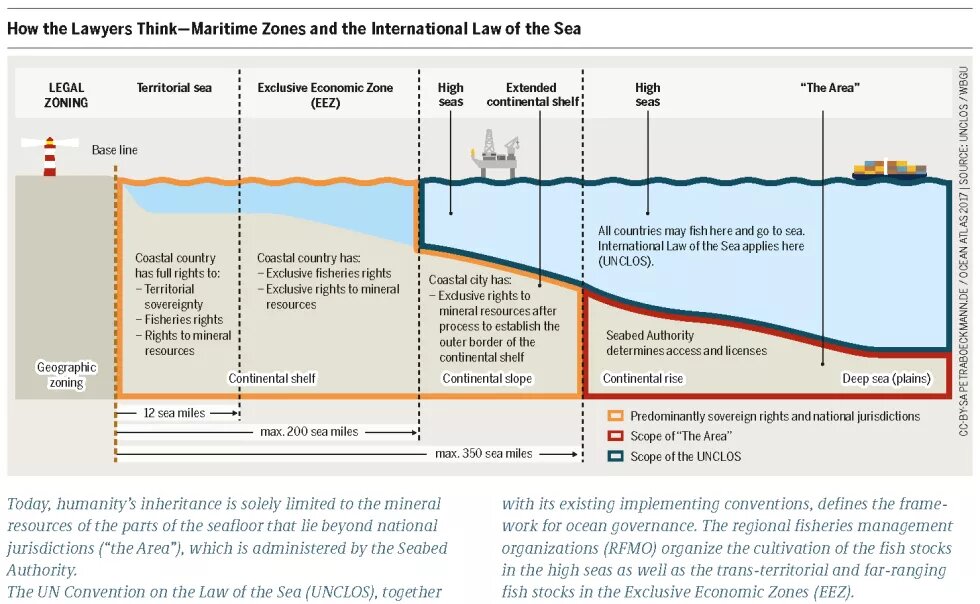

The foundation is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982). It says that a country may claim an area extending 12 nautical miles from its coast as its own territorial sea. Additionally it can exploit 200 nautical miles of the water column beyond its coast as its exclusive economic zone. The same applies to the first 200 nautical miles of the sea floor, the continental shelf. The resources found there can be exploited by that country alone. And that is not all. If the country can scientifically prove that its continental shelf extends even further – that it is continuously geologically connected to the mainland – it also has the sole rights to the resources there as well. This territorial claim includes islands but not rocks or other outcroppings.

This is particularly interesting for some uninhabited islands like Heard Island and the McDonald Islands. They are tiny islands located 1,000 kilometers north of eastern Antarctica. Thanks to them, Australia has secured a geological exploitation area of more than 2.5 million square meters. That’s because these islands stand on the undersea Kerguelen Plateau, a gigantic mountain range that stretches more than 2,000 kilometers. Australia can now claim exclusive exploitation rights to it. The convention does place some limits on this, but the rights may still extend up to 350 nautical miles from the island.

The Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982), which is considered to be the constitution of the ocean and is intended to peacefully adjudicate the interests of all states, is still relatively young. Its approach to the areas of the ocean floor that lie totally outside national sovereignty and national exploitation rights – referred to simply as “the area” in the language of the UN – is actually based on the concept of “the shared heritage of humanity.” It is intended to guarantee that the environment is protected and that developing nations also have their share of the riches.

These strong words sometimes achieve only weak results. When a country can legally expand its exclusive economic zone, it reduces the shared inheritance. Consider the case of Norway, which has reserved an exclusive economic zone of 500,000 square kilometers thanks to its ownership of Bouvet Island, a small “island” completely covered in ice and lacking fresh water located in the South Atlantic, 2,600 kilometers from the Cape of Good Hope. France has also swelled in size thanks to many far-flung island dependencies – it is still “la grande nation” when it comes to stockpiling the treasures of the ocean floor.

In establishing these claims the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf plays an important role. There, states secure rights to raw material reserves that are sometimes only partly economically ascertainable or that are only suspected to exist – unknown chances of future riches, so to speak. It is not just a matter of fossil fuels, ores, metals, and the power that comes from their control. It is also about the global strategic interests of the states in legally expanding their spheres of influence. The remaining unclaimed “area” shrinks. It has already declined from more than 70 percent of the sea floor to just 43 percent. 57 percent of the ocean floor has already been parceled out. And as the international area shrinks, so does the ability of international influence to ensure that all nations have an opportunity to participate and that resources are fairly distributed.

These regulations are only related to the ocean floor. But the masses of water above, and everything that happens in and on them, are also subject to legal regulations. Within the economic zones, national laws apply to the exploitation of resources and environmental protection. Additionally, the law of the high seas applies – it is part of international law. But it also has loopholes: pirates can be detained by anyone who catches them, but not polluters, illegal fishing fleets, terrorists, weapons dealers, drug smugglers, or human trackers. They can only be pursued by the countries from which they originate. It is often more than unclear who the responsible international organizations are. Territorially speaking, the high seas belong to no one – and so when it comes to exploitation, they belong to everyone. It is thus difficult to advance the protection of the ocean with reference to global problems. But it is not impossible, as current negotiations to create protected zones in the high seas at the EU level may prove.

» You can download the entire Ocean Atlas here.