Coal is one of the dirtiest industries in Russia. Apart from hydropower, renewable energy is practically non-existent. Civil society groups that might push for more sustainable sources of power are few and far between. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

The Russian Federation has the world’s second-largest coal reserves, and coal is produced in 25 of its constituent territories. Over half (52 percent) comes from the Kuznetskiy basin, and another 12 percent from the Kansk-Achinsk basin. The Pechora basin contributes 5 percent, while the East Donets and South Yakutsk fields contribute 3 percent each. The Kuznetskiy basin, or Kuzbass, in the Kemerovo Region of Western Siberia is the most important coal supplier, and Russia’s rising production over the past ten years have been due mainly to new production capacities in this region.

Seventy percent of Russia’s coal is currently produced from open-cast mines. The industry, which is composed entirely of privately owned companies, employs around 150,000 people. Among the largest producers and exporters are SUEK, Kuzbassrazrezugol, SDS, Mechel, and KTK.

Over 170 power plants in Russia run on coal. More than 80 percent of these plants are over 20 years old, and some have an electrical efficiency of only 23 percent. New coal-fired plants abroad can achieve 46 percent efficiency.

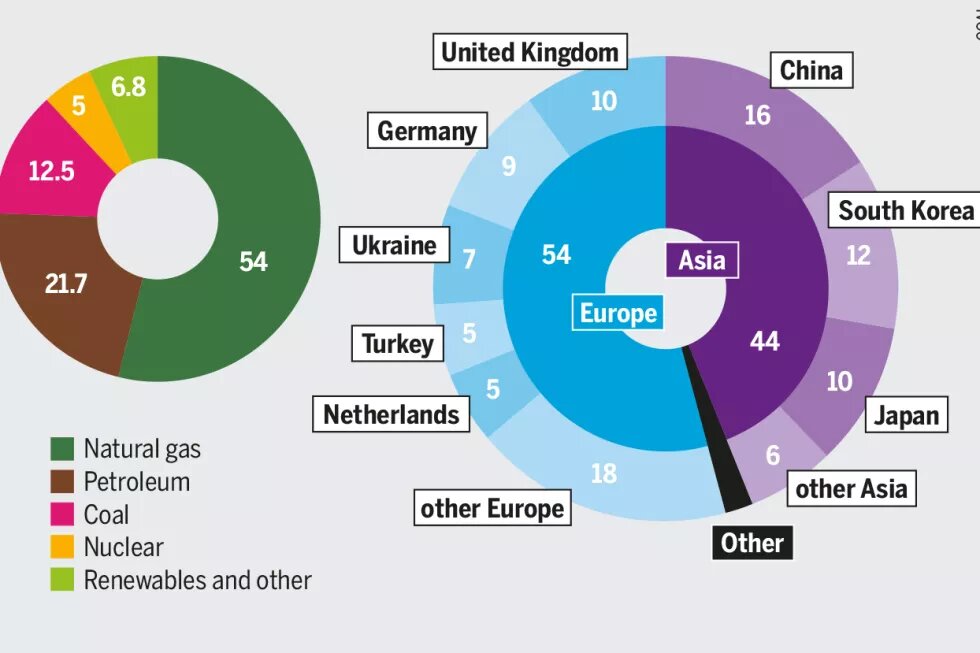

In 2013, Russia was the world’s third-largest coal exporter, after Indonesia and Australia. It ships coal to nearly 50 countries. Germany and the United Kingdom are its biggest customers in Europe.

The Russian government support for the coal industry includes around $7 billion in subsidies supplied by the state budget until 2030. The government plans to use local coal reserves to generate more power in Siberia and the Far East. These include the Yelginskoye field in South Yakutia, Syradasaiskoye in the Krasnoyarsk Region, and Udokanskoye in the Chita Region. That would mean a series of power plants with a combined capacity of over 10 gigawatts is due to go online between 2020 and 2022. It also paves the way for major investments that envision exporting over 50 billion kilowatt-hours to China.

ach year, 360 million cubic metres of air are blown into Russian underground mines, and over 200 million tonnes of water are pumped out. At open-cast mines, between 300 million and 350 million tonnes of rock are shifted into waste dumps.

Drilling and blasting operations, exhaust from vehicles used to excavate the coal, emissions from power plants, and fires caused by the spontaneous ignition of coal during mining and processing are all sources of air pollution. With open-cast mining, solid particles – inorganic dust containing silicon dioxide, coal ash and black carbon (soot) – are the main pollutants. In the Kemerovo Region alone every year, over 1.5 million tonnes of pollutants are emitted into the atmosphere, and over half a million cubic metres of polluted wastewater are discharged. A 2011 report on the state of the environment in the region estimates that the average concentrations of harmful air pollutants were two or three times higher than the allowable maximum in Russia. On a number of occasions, they exceeded these limits by as much as 18 times.

Coal mining affects not just the area immediately around the mines, but neighbouring areas as well. Cities in mining areas, such as the Kuzbass and Vorkuta regions, typically suffer from high concentrations of suspended particles in the air. Raised levels of lead, cadmium, mercury and arsenic are found in locally grown food.

The grime shows its effects in disease patterns. In the Kemerovo Region, where coal is the biggest polluter, respiratory ailments were the most common type of ailment, affecting 23.5 percent of patients seeking medical assistance. The health risks are highest for pregnant women and children. In the past decade, disease rates among pregnant women in the region have risen almost fivefold. Maternal mortality rates are double the Russian average.

Russia’s energy mix currently consists of gas (54 percent of primary energy consumption), oil (21.7 percent), coal (12.5 percent) and nuclear (5 percent). Almost all the rest comes from large hydropower plants. Renewables are next to invisible; they are regarded as suitable only for places not connected to the grid. The Ministry of Energy says that there will be no federal funding for regional energy-efficiency programmes in 2015 due to the economic crisis.

There is no political debate on the future of the coal industry in Russia. The government sees the sector as an important exporter of fossil fuels and as a big employer. Historically, civil society has never been very active on coal-related issues. Moreover, the environmental movement is under heavy pressure as the government shuts down critical voices. Civil society is showing signs of interest in examining the environmental damage caused by coal, but it is hard to predict whether this will grow into a strong movement in Russia’s politically hostile conditions.