Successful climate policies mean that coal is becoming a less valuable resource. This affects the companies that dig it up. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

In 2009, a team of researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research published a ground-breaking study calculating the size of the global carbon budget. That is the amount of CO2 that can be emitted if the rise in the Earth’s surface temperature is to be held below 2 degrees Celsius. A key finding: if we continue pumping out as much greenhouse gas into the atmosphere as we have so far, we will have used up the budget in just 14 years – and the temperature will rise more than 2°C. In addition, it means that the carbon budget sets a limit to the amount of coal, oil and gas we can burn. All the fossil energy sources beyond this limit are “unburnable carbon” – a phrase coined by the Carbon Tracker Initiative that has become an important measure in global climate policymaking. The Carbon Tracker Initiative calculates that 2,795 gigatonnes of CO2 are stored in oil, gas and coal reserves in private and government hands and listed on stock exchanges. Compare that to the global carbon budget of 565 gigatonnes. In a nutshell: four-fifths of the reserves are “unburnable carbon”.

Two scientists at University College London have worked out what these calculations imply for the use of individual fossil fuels in different locations. They published their findings in the journal Nature at the beginning of 2015: to keep within the 2°C limit, we can burn only about 12 percent of current global coal reserves, two thirds of the oil and about 50 percent of the natural gas reserves. The restrictions would be even tighter if we are to keep within a 1.5°C rise, as recommended by climate science.

Policy decisions and lower market prices for energy, partly as a result of advances in renewable energy, could leave most fossil-fuel investments as “stranded assets”. Against investors’ expectations, such assets would bring in no profit; on the contrary, they would have to be written off as more or less worthless. The Carbon Tracker Initiative calls this misinvestment problem the “carbon bubble”; named after the speculative peaks in the world of finance, such as the property bubble that sparked the economic crisis in 2008. The phenomenon is not restricted to coal: oil and gas reserves are also affected.

Despite this, private and government financial institutions continue to invest in the companies affected, or to grant credit on the basis of the previous policy situation. Fossil-fuel reserves are included in the trading value of companies: the production licenses of mining companies, the generation capacity of power producers, and the investments by banks in these firms. If the bubble bursts, these companies will see their value crash.

A study commissioned by the European Greens looked into the risks in 2014 for 43 of the EU’s biggest banks and pension funds. It identified a total of over one trillion euros. The good news: some funds have already started to divest themselves of these holdings in order to avoid a crisis if the investments in coal and oil become “stranded”. In June 2015, the Norwegian parliament voted to remove coal firms from the investment portfolio of the country’s pension fund. This is the biggest divestment so far by a single investor, which is also Europe’s largest pension fund.

Many governments are concerned about the financial risk represented by the carbon bubble. Divesting from coal now is necessary to prevent disastrous climate change and a global financial crisis. The big coal producers at least partly recognize the sign of the times. E.ON, Germany’s biggest power firm, is splitting in two. One part of the firm will focus on renewable energy and power services, while the rest will be responsible for conventional power plants. Rio Tinto, a mining multinational, has hived off its coal investments into a separate firm while signalling it will move away from this type of mining. Its competitor, BHP-Billiton, has also parted coal investments into a separate firm, thereby halving its coal activities.

These actions are late. In Europe, power firms have lost touch with developments because they have not changed their strategy quickly enough. Only eight percent of German investments in renewables came from power suppliers like E.ON and RWE. In 2014, the French energy giant GDF Suez had to write off stranded assets to the value of 15 billion euros. The power firms did not take the EU’s goal of reducing emissions by 2020 seriously. They assumed that energy efficiency and renewables would be long in coming, if they arrived at all.

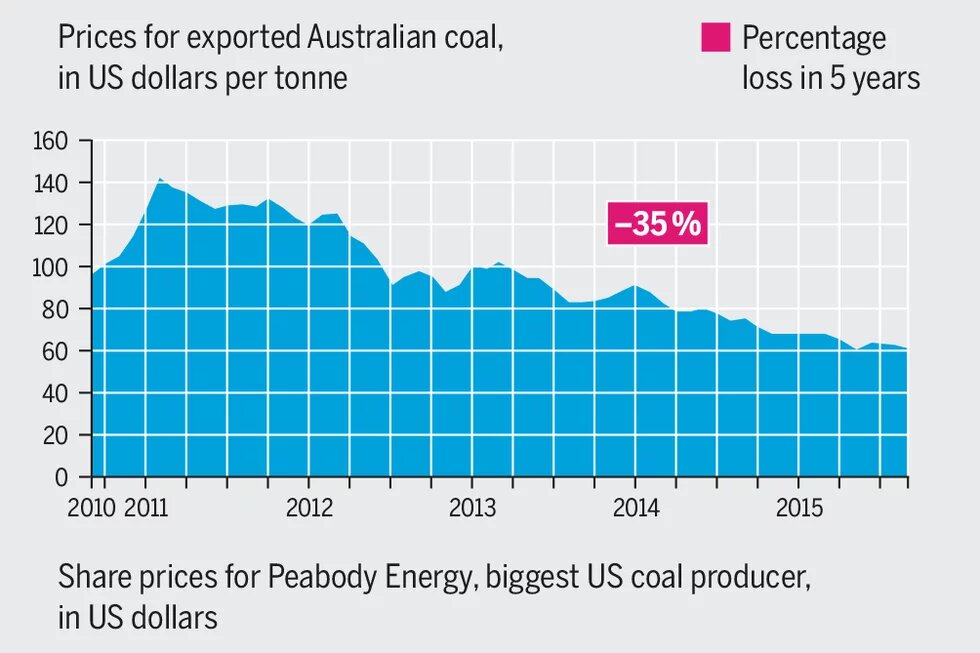

The coal industry is now waking up. Low prices on the world market are putting revenues and profitability on hold. In 2014, coal consumption in China, the biggest consumer, fell for the first time on record. In an effort to reduce air pollution, the country is consuming significantly less. Demand in the United States and Europe is also declining; rising consumption in India cannot make up the difference. As a result, coal prices have halved from a peak in 2011, and are now as low as during the global financial crisis in 2008. Low world prices affect the Chinese market too, bringing losses to coal producers there. In mid-December 2014, Glencore, a mining giant, shut its 20 mines in Australia for three weeks and told 8,000 workers to take their annual leave – a sign of the depth of problems faced by the industry.

Investors should perhaps regard some coal producers themselves as “stranded assets”. Political moves to reduce carbon emissions and develop alternative technologies send the right signals to chief financial officers. More important still, companies in the fossil-fuel sector are also getting a clear message; they should not waste any more money looking for new reserves.