Open-cast mining destroys the landscape of both the pit and the surrounding area. Efforts to restore these areas often fail and the surface above the underground mines sinks. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

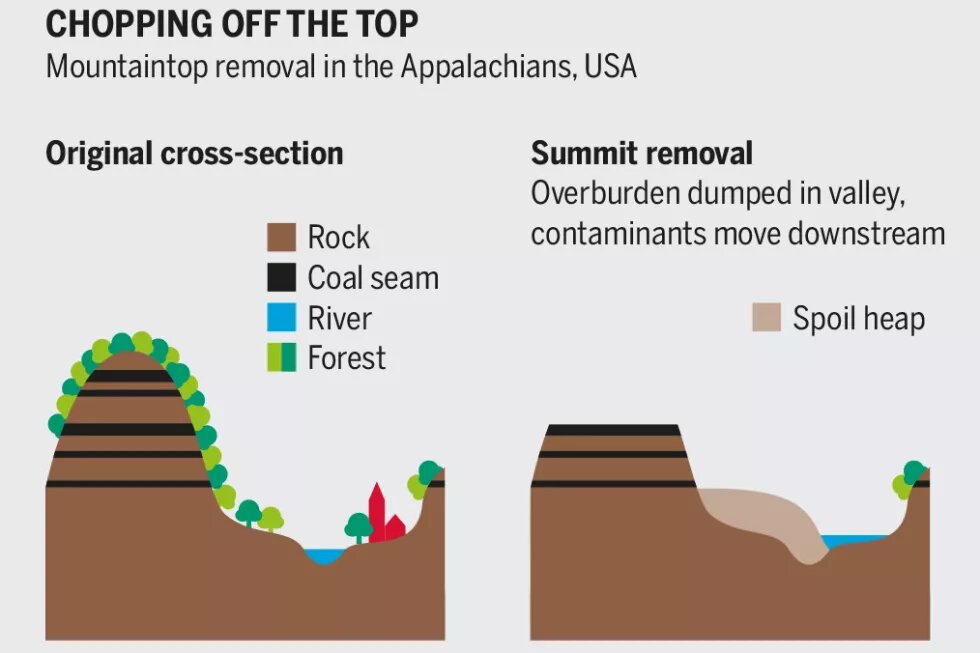

Coal extraction has huge impacts on the environment. In open-pit mining, which accounts for about 40 percent of global coal production, the entire overburden has to be removed to reach the coal seams underneath. The landscape is completely destroyed. Communities are removed, plants and animals are eliminated, and the living soil is shovelled away. Excavators dig enormous craters, hundreds of metres deep. Appalachia, in the United States, has a particularly extreme form of open-pit mining: to get at the coal, entire mountaintops are blasted away and the rubble is dumped in the valleys.

Our planet is littered with thousands of coal mines. The largest mine in the world, measured in terms of reserves, is the North Antelope Rochelle Mine in Wyoming, in the western United States that is estimated to hold some 2.3 billion tonnes of coal. It produces over 100 million tonnes annually from a vast open pit covering 250 square kilometres. The second-largest operation is the Haerwusu Mine in Inner Mongolia in China. This mine has an estimated 1.7 billion tonnes of reserves and an annual output of 20 million tonnes. It covers over 67 square kilometres. Other mega-mines can be found in Australia, Colombia, Indonesia, Mozambique, Russia and South Africa.

The ecological consequences are similar across countries, though standards for mining, restoration and legal enforcement differ widely. Mining means digging up and shifting huge amounts of earth. In some types of soil, iron and sulphur compounds can oxidize to iron and sulphate when they come into contact with the air. After extraction ceases the groundwater levels rise again and sulphuric acid is produced. As a result, the flooded pits and groundwater acidify. Adding alkaline materials such as limestone can reduce the level of acidity but cannot prevent it completely. Some of the iron that is set free is converted to iron hydroxide, or limonite. This rust-coloured mineral clogs pipes and pumps, blankets the spawning grounds of fish, and smothers their food supply.

Pumps are used to lower the water table and prevent the pits from filling up with water. This has severe consequences for the groundwater. In Germany’s largest open-pit mine, at Hambach, this will require pumping out almost 45 billion cubic metres of groundwater over the next 60 years the mine is expected to be in operation. Keeping a mine dry disrupts the hydrology of the neighbouring areas: lowering the water table by as much as 550 metres dries up the springs that feed rivers, kills trees, desiccates wetlands and reduces biodiversity. This pumping, or what the experts call "mine dewatering", may also dry up wells, endangering drinking water supplies. It can take a hundred years for the groundwater level to regain its previous level.

Mozambique’s Tete province used to be famous for its beautiful baobab trees, many over 1,000 years old. But coal-mining companies have destroyed vast numbers of them, ignoring their importance for the environment, local culture and peoples’ diets. Such trees may take hundreds of years to regrow. Clouds of coal dust, polluted water and soil contaminated by acid drainage from mines also harm local communities. None of the companies operating in Mozambique have published environmental management plans, leaving the public ignorant of the environmental consequences of their operations.

In Nigeria, the government has signed a memorandum of understanding with the Chinese firm HTG-Pacific Energy to exploit coal in Enugu, in the southeast of the country. But no environmental impact assessment has been made – though this is required by law – and the right of affected communities to be involved in the project development has been ignored.

Cerrejón, a massive open-cast mine in Colombia, has impoverished the surrounding soils and contaminated or dried up water sources, with devastating impacts on farming and livestock keeping. The whole mining complex here extends over 69,000 hectares. Ninety percent of Cerrejón’s hard coal is shipped abroad to fuel power plants, mainly in Europe and the United States.

While becoming the world’s largest coal exporter, Indonesia has destroyed vast areas of rainforest and deprived local people of their land and homes. In Borneo, the indigenous Dayak people are fighting against mining companies’ activities, particularly against the mining giant, BHP Billiton. The Dayak are trying to stop a series of large coal mines and railways that would decimate primary rainforest, pollute water sources, displace indigenous peoples and endanger orangutans. This project would destroy the headwaters of 14 major rivers that provide clean water to 11 million people.

Coal mining leaves its mark on the landscape in other ways too. Lethal landslides can occur in open-cast pits decades after mining operations have ceased. Underground mines cause surface subsidence that damages buildings and roads. These "inherited liabilities" will continue to be a burden to future generations. In the Ruhrgebiet, a mining and industrial area in western Germany, water has to be pumped out of abandoned underground pits to stop the water table from rising too high, and in some areas continuous pumping is needed to prevent entire neighbourhoods from being flooded.

The ash from power plants also gives cause for concern. Landfills that store this toxic by-product of coal burning are often inadequately secured, allowing the ash to leak out. A particularly serious case occurred in 2008 in Tennessee, in the eastern USA. A retaining dam next to the Kingston coal-fired power station collapsed. Four million cubic meters of ash sludge containing heavy metals were released, carpeting the surrounding areas and polluting a nearby river.